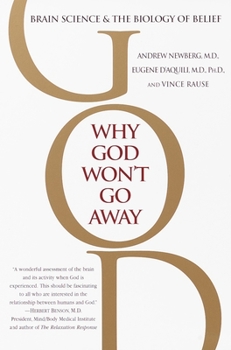

Why God Won't Go Away: Brain Science and the Biology of Belief

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Why have we humans always longed to connect with something larger than ourselves? Even today in our technologically advanced age, more than seventy percent of Americans claim to believe in God. Why, in short, won't God go away? In this groundbreaking new book, researchers Andrew Newberg and Eugene d'Aquili offer an explanation that is at once profoundly simple and scientifically precise- The religious impulse is rooted in the biology of the brain...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:034544034X

ISBN13:9780345440341

Release Date:March 2002

Publisher:Random House Publishing Group

Length:240 Pages

Weight:0.51 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 5.6" x 8.3"

Related Subjects

Anatomy Behavioral Sciences Biological Sciences Christian Books & Bibles Christian Living Cognitive Psychology Education & Reference Health, Fitness & Dieting Health, Fitness & Dieting History & Philosophy Psychology Psychology & Counseling Religion Religion & Spirituality Religious Studies Science Science & Math Science & Religion Science & Scientists Science & TechnologyCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

Toward Bridging the Gap

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This book is an excellent engagement of several critical and interesting issues on the nature of spiritual experience and accompanying belief systems. As scientists with apparently little earlier background in religion and spirituality, the authors do a good job in getting to the bottom of what inspires religious beliefs--ultimately, in their view, a profound "spiritual" experience had by mystics, shamans, and others from diverse cultures all over the globe. They explain the neurology of how this likely works, in understandable lay terms. Along with this is a studied attempt to set it all in an evolutionary context. Yet this does not lead them to eliminate the possibility of actual spiritual reality behind the biology and its evolution. This is a very helpful approach, as opposed to the absolutism and reductionism of a decreasing number, but still the strong majority of scientists. As a serious, long-time student of religion, I found their attitude toward religious beliefs respectful and their analysis careful. Still, their approach is primarily scientific, and makes a contribution to our knowledge of the important biological processes assisting the development of religious beliefs. Their approach is not simplistic, and was I intrigued to see that at least Dr. Newberg (his co-author, Dr. D'Aquili, died prior to the book's completion) seemed to personally be opened, by his research, toward acceptance of spiritual experiences as perhaps genuine windows into a larger-than-material reality. Yet, he is careful to indicate where he is speculating versus where he is reporting solid science. People who want only science, only hard data, or struggle intellectually with the increasingly common science-theology interface that this book indulges, will find reason to object. But this book makes a contribution to that body of literature, which continues to grow. These works, of which "Why God Won't Go Away" is a prime example, enlighten our understanding of what makes good sense and is pro-social and healthy in spirituality versus what is dysfunctional. I greatly appreciated the final chapter, which has been and will be debated and objected to by some. In it, the authors make the solid point that science itself involves "a type of mythology, a collection of explanatory stories that resolve the mysteries of existence and help us cope with the challenges of life" (p. 170). Another way of saying what I think they mean is that everyone, including scientists, are "religious" in the broadest sense of the word. The kind of work represented in this book helps foster clearer and deeper dialog between two realms which are often too rigidly set against one another. The authors caution against taking literally the "foundational assumptions" of either religion or science. "But if we understand the metaphorical nature of their insights, then their incompatibilities are reconciled, and each becomes more powerfully and transcendently real" (p. 171).

Groundbreaking research on spirituality and the brain

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

There are only a handful of books that have attempted to map the biology of spiritual experiences (Goleman's "Destructive Emotions," Hamer's "The God Gene" and Austin's "Zen and the Brain,"for example), and Newberg is one of the first neuroscientists to use brain-scan technology to peer inside the minds of Buddhist meditators and Franciscan nuns as they pray. But neuroscience is in its infancy, so any book on the topic is going to be highly speculative for at least the next 10 years. Newberg's work does show that specific neurological changes take place when one intensely meditates or prays, and this accounts for the alterations in our perceived sense of reality. We "lose ourselves" or feel "at one" with god or the universe because those parts of the brain that maintain a sense of self and otherness are temporarily suspended. Thus, the person does experience a new reality, and as far as the brain is concerned, that reality is as real as any other because it is based on direct experience. The skeptic will say that it is a neurological illusion created within the brain, while the believer will say that this is evidence that a spiritual realm exists. In fact, neuroscience supports neither view, for the brain is both observer and producer of reality. The brain can operate in ways that make spiritual experiences feel real--and this is one of the astonishing facts that Newberg has been able to substantiate--but the brain does not have a way to get outside of itself to objectively verify the experience. This has been the conundrum in philosophy of consciousness arguments for years. Newberg's book and research is important because it allows both believers and disbelievers to understand how the brain perceives and interprets information that extends beyond the boundaries of everyday human experience. His next book, due out in September of 2006, is called "Why We Believe What We Believe" and it extends his brain-scan research into the minds of atheists and Pentecostalists as they speak in tongues (this was recently filmed by National Geographic on a progam called "Exorcism"). "Why God Won't Go Away" will equally provoke and inspire, depending on what you already believe, or want to believe.

A Neuroscientist Unashamed

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Neuroscientists have an irrepressible penchant for speculating about the significance of their findings. For instance, Eric Kandel - Nobel Laureate, in his public appearances talks about his field, Long Term Potentiation, as though it were the basis of all learning in creatures with nervous systems. This is to any of us in the field stretching things a bit, but we like it.Andrew Newberg with the late D'Aquili have put scientific observation inside the spiritual experience. They found a specific area of the parietal lobe lit up in some clever experiments. Is this area of the parietal lobe bound up with our sense of selfhood? Andrew Newberg runs with this idea in a breezy read.Of course, as practicing neuroscientists we know that so many of these great discoveries fall down after a very short run. So, this book is not one that sets a landmark for truth, but it is a landmark in bringing neuroscience and spirituality together in a satisfying fashion.Newberg does not pretend to get technical in this essay. Thus, those of you who are looking for new information about the brain should look elsewhere. But those of you who know about the brain already will find this book novel in its application of what is known about the brain to the spiritual domain.As a bachelor of philosophy and now practicing neuroscientist I found it difficult to put this book down.

Excellent overview of the science of religious experience

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

There is a very good overview of current scientific research and argument regarding the nature of religious and mystical exerience here. Recent research into the neurological origins of religion, the stunning compatibilities between various religious myths and inclinations, the function and universality of ritual (across the animal kingdom), the commonness of lesser mystical experience and ritual-such as music, art, or by simply taking a bath, and the social cohesian and function that religion plays in virtually any society, are all discussed. The book also details the long standing arguments about whether various deep religious experience is an expression of some kind of mental disorder(s), or a higher brain function useful for specific purposes. It notes for example that highly religious persons throughout the ages have often also been significant achievers. This appears to be imcompatible with the notion that they are 'mentally disordered'. The book asserts that for whatever reason 'altered brain states' occur, there was/is a significant evolutionary reason for them to have been selected in the first place. This is an important point;- altered brain states, including mystical/religious experience, probably had their origin in the struggle for existance, which was then utilised for other circumstances. The origin of myth-making and ritual in the human condition for example, is discussed in this way. There are also discussions on the importance of conflict, contradiction and resolution in religious ritual and myth, and their likely evolutionary origins.Many of the books early assertions appear to be summations and ideas strung together from elsewhere, but the book in the second half becomes more controversial in asserting that the altered mental states or 'higher reality', as described variously by mystics, may in fact BE an alternative/higher reality, and not a cultural interpretation of unusual brain functioning. This is a bold assertion, which requires some weighty evidence. The evidence presented in this book however appears to rest mostly on shaky anecdotal support, "I experienced a highly significant event, therefore my interpretation of this event must also be correct". The authors suggest that various mystical/religious experience may imply the existance of an independant 'higher reality', which brain evolution has already cottoned onto. The authors seem to suggest that whilst most people who have some kind of religious experience do in fact misinterpret them, it is still possible that they are ultimately right-an independant and profound reality exists, independent of the evolution of the senses and the self. Whilst conceding the possibility, I personally need more evidence of this concept of 'God' to accept that this experience isn't just a fundamentally important ability of the brain, to give us survival, purpose and meaning, but not necassarily a connection to an external 'God' or 'reality', however you may want to define this 'reali

God in the Brain's Machine?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Science cannot determine that gods of any type exist, nor can it determine that no gods exist. However, there may be scientific reasons why the belief in gods remains strong. In the surprisingly titled _Why God Won't Go Away_ Ballantine Books) by Andrew Newberg, M.D., Eugene D'Aquilli, M.D., and Vince Rause, we get a fascinating scientific answer to the title question, and a review of the current scientific understanding of the roots of belief. The authors have done research by means of brain scans on those who are having mystical or religious experiences. The brain scans show that something is going on among the neurons that doesn't happen at other times. Most of the scans described in the authors' research show an increase in activity in the posterior superior parietal lobe, an area just behind the top of the head. They call this for operational purposes the "orientation association area (OAA)," because the OAA orients a person in physical space. "To perform this crucial function, it must first generate a clear, consistent cognition of the physical limits of the self. In simple terms, it must draw a sharp distinction between the individual and everything else; to sort out the you from the infinite not-you that makes up the rest of the universe." When this area is damaged by trauma or stroke, patients have difficulty maneuvering in physical space; when it is extra active, it seems to be a source of an inexplicable feeling of connection to all creation. A meditator describes the ineffable state in terms that are typical: "There's a sense of timelessness and infinity. It feels like I am part of everyone and everything in existence."The authors explain that the gene-driven wiring of the brain to encourage religious beliefs exists because it has been evolutionarily good for us. Stimulating the OAA or the autonomic nervous system can produce calm and a sense of well-being which may be not only pleasant but physically beneficial. Beliefs driven by neurology could reinforce themselves by building myths, encouraging ritual, uniting societies and providing social support from fellow believers. They can check worry about eventual annihilation. They can provide a feeling of control.Those of a religious bent will find matter to argue with inside these pages, even though the authors are very careful not to argue for or against the existence of deities, only that "the neurological aspects of spiritual experience support the sense of the realness of God." Some may also find disconcerting the idea that ecstasy of religious mysticism may have its roots in the structures that bring on orgasm. Others will find the practical answer to the title's question just too pragmatic and pat, but given the extraordinary research as it now stands, it is the best that science can do as it begins to look into religious feeling: "What we know beyond question is that the mind is essentially a machine designed to solve the riddles of existence, and as long as our