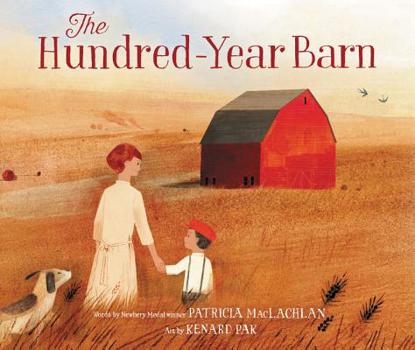

The Hundred-Year Barn

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Newbery Medal-winning author Patricia MacLachlan's poignant text and award-winning artist Kenard Pak's gentle and rustic illustrations paint the picture of a beautiful red barn and the people who call it home.

One hundred years ago, a little boy watched his family and community come together to build a grand red barn. This barn become his refuge and home--a place to play with friends and farm animals alike.

As seasons passed, the barn weathered many storms. The boy left and returned a young man, to help on the farm and to care for the barn again. The barn has stood for one hundred years, and it will stand for a hundred more: a symbol of peace, stability, caring and community.

In this joyful celebration generations of family and their tender connection to the barn, Newbery Medal-winning author Patricia MacLachlan and award-winning artist Kenard Pak spin a tender and timeless story about the simple moments that make up a lifetime.

This beautiful picture book is perfect for young children who are curious about history and farm life.

* Bank Street College of Education Best Children's Book of the Year (2020) *

Related Subjects

British & Irish Continental European Drama Fiction Literature & Fiction World LiteratureCustomer Reviews

Waiting For Godot Mentions in Our Blog

Treat your April-born friends and family to a bookish birthday! Did you know you can schedule ThriftBooks e-Gift Cards to be delivered on a specific date? Or If you'd rather give your April amigo something special, we've put together a list of some of the hottest titles of the moment. Plus, learn about literary luminaries born this month.