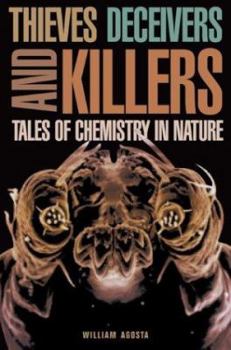

Thieves Deceivers and Killers: Tales of Chemistry in Nature

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The tobacco plant synthesizes nicotine to protect itself from herbivores. The female moth broadcasts sex pheromones to attract a mate, while a soldier ant deploys an alarm pheromone to call for help. The carbon dioxide on a mammal's breath beckons hungry ticks and mosquitoes, while a flower's fragrance speaks to the honey bee. Indeed, much of the communication that occurs within and between various species of organisms is done not by sight, sound,...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0691092737

ISBN13:9780691092737

Release Date:March 2002

Publisher:Princeton University Press

Length:241 Pages

Weight:0.80 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 6.0" x 9.4"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

Tantalizing view of a wild world that surrounds us

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Very interesting Wish for more chemical structures and references would make it easier to follow up on. Certainly makes the worl of chemical sensing come alive o

great insight into insects, ants and other fascinating creatures

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Protos, Prof. William Agosta's opening chapter explains, have kept Lept slaves from time immemorial. The slaves raise their young, gather food for them and keep their homes clean. The Protos excel only at capturing the Lepts, who are remarkably loyal to their Proto masters, even becoming ferocious participants in slave-raids on their own kind. Both the Protos and Lepts are tiny ants, who live out their inter dependent lives in a world no bigger than a dinner table. They are only one of the many mysteries of nature this fascinating book brings to our attention. Whereas stick insects use ants to disperse their eggs, the scuttle fly lays its eggs in the heads of the unfortunate ants it preys on. Some wasps lay their eggs within the eggs of stick insects while others fool ants into believing that their offspring are ants. The South American crab spider fools carpenter ants by carrying a dead ant in such a way that it walks, smells and looks like an ant. This neat trick allows the spider ant to capture and kill another dumb ant and repeat its bizarre ritual. Because some 289,000 species of insects act as pollinators of flowering plan, Agosta's fine book shows how and why a lot of deals are cut for self-survival reasons. A single pound of honey, for example, represents the nectar from about 17,000 foraging trips and entails 7,000 bee-hours of labor. The flowers must have all kinds of sophisticated strategies to ensure the busy bees spread their seed. The rhizanthella gardneri, an Australian orchid, must have a peculiarly singular strategy; this is because it blooms underground and depends on scuttle flies to pollinate it. Chimpanzees and parrots, meanwhile, eat special plants when they are sick and some bacteria contain particles that act as compasses. Life is strange - especially, as Agosta explains, for flower mites, which hitch rides with migrating hummingbirds, spending their summers on the California coast and winter in west-central Mexico. They do this by climbing into the bird's nostrils and alighting at the right flower to survive. They have less than 5 seconds to alight and achieve their "Mission Impossible". Older female mice, meanwhile, trick younger ones into not procreating, a case perhaps of brains over beauty! As well as discussing a fascinating number of such examples, Agosta ventures further to show how history has been influenced by the lowliest of creatures. Although we generally loathe flies as disgusting creatures, without them, the author shows how our destiny would have been vastly different. Their diseases decimated Napoleon's Haitian army, forced him to sell Louisiana for a pittance to the United States and to abandon the Americas almost entirely. Malaria caused five times more casualties in the Pacific war than did the combatants. Because it is so lethal to humans and their domesticated animals, the tsetse fly keeps large swathes of Africa relatively underdeveloped. However, we are now using cattle urine to trap and exter

Tales of Chemistry in Nature

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This book is an information feast, digestible in small bites but too rich to be downed in a single gulp. It's an incredible collection of stories bound together by the thread of `chemistry in nature.' In fact, one of the stories concerns threads---the ancient Romans used to weave a sheer fabric called `linen mist' from the byssal threads of a large mollusk known as the noble pen shell (`Pinna nobilis').Many of the lessons in chemical ecology concern ants and their sophisticated use of biochemicals to take slaves, grow crops, and manufacture antibiotics. In another chapter called "Real-World Complexities," the author maps the annual fluctuation of Lyme disease as dependent on the interaction of deer, bacteria-carrying deer ticks, mice, oaks, and gypsy moths. If only we could learn from these chemical interactions, before we destroy their ecology.The author gives tantalizing glimpses at antibiotics, extremophile enzymes that don't break down when used as catalysts, fishing nets that are made out of spider webs, and many other ways we could capitalize on ecology if we took the time to learn from it.There are many good science project ideas in "Tales of Chemistry in Nature." The book can be profitably read by adults and young adults. For adults already advancing down their chosen career paths, this book is a fascinating look at what the biochemists and ecologists may be learning from nature.

Better living through chemistry?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The central message of this gracefully written, highly informative, and refreshingly modest book by Rockefeller University Professor Emeritus William Agosta is that there is a wealth of chemicals produced in nature that humans can effectively use to fight disease, control pests, and facilitate chemical reactions--if only we can find, understand and harvest them.Agosta begins with a tale about a species of ant that enslaves members of another species using a variety of chemicals. He ends the book with the idea that we might find desperately needed new antibiotics by examining the chemicals made by animals "that form herds or flocks, as well as those that live in organized societies, such as the social insects..." (p. 212) Agosta's rationale is that other social creatures face the same danger that humans face, that of pathogens that rapidly spread in a crowd. Surely they have come up with some chemical defenses we might discover and employ ourselves. He cites ants as a particularly likely prospect for study and gives the example of the bulldog ants of Australia who, when injected with the common human intestinal bacterium, Escherichia coli, manufacture an antibiotic that promptly kills it.In between the bookend chapters, Agosta spins tales about how microbes and insects, plants and sea creatures, fungi and arachnids attract, repeal, steal from, deceive, enslave, parasitize and kill one another, mainly with chemicals. The world he depicts is largely a world where eyes and ears are secondary to the sense of smell, a bizarre fairy land of complicated arrangements among species and delicate ecologies. A case in point is the in-door farm of the leaf-cutting ant which involves not only the ants and the trees they get the leaves from and the fungus they grow, but also the use of a species of streptomyces to produce an antibiotic to kill a fungal pest in their gardens. In other words, not only are ants farmers, they use pesticides!Agosta emphasizes that we must understand the interactions of species to appreciate their use of chemicals. He uses the phenomenon of Lyme disease as an example, and how it is affected by the mass fruiting cycle of oak tree acorns which influence the numbers of mice and deer on which the ticks that harbor the Lyme disease parasites live. Two years after a bumper crop of acorns there is a concomitant rise in the number of people who get Lyme disease.In particular, these are tales of parasite and host. I was startled to learn on page 223 that ticks and mites are so prevalent that they have "parasitized almost every organism larger than themselves." Indeed, something similar can be said of the nematodes (roundworms) who "have parasitized virtually every species larger than themselves." (p. 224) When one thinks about the countless viruses and bacteria that prey on humans and all the other animals and plants, one realizes that we live in a world of parasites.However, the single most startling and mind-expanding thing I rea