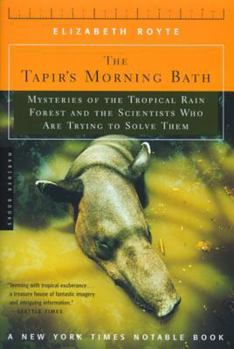

The Tapir's Morning Bath: Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest and the Scientists Who Are Trying to Solve Them

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

One hundred and fifty years ago, Charles Darwin asked how a rain forest could contain so many species: "What explains the riot?" The same question occupies the scientists who toil on Panama's Barro Colorado Island today. Tropical and steamy, these six square miles comprise the best-studied rain forest in the world, a locus of scientific activity since 1923.

In THE TAPIR'S MORNING BATH, Elizabeth Royte weaves together her own adventures on Barro...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0618257586

ISBN13:9780618257584

Release Date:November 2002

Publisher:Houghton Mifflin

Length:336 Pages

Weight:0.70 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.7" x 8.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

journey of discovery

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

On the trail of the scientists who make the trailsA journalist follows researchers into the South American rain forest to study the mystery of their devotionBy Diana Muir Deep in the tropical rain forest, a small fruit-eating bat carefully nicks the veins on the underside of a philodendron leaf, causing the edges to fold down like a miniature tent. The bat curls up under its little tent and goes to sleep. Other bats don't make tents, why do these? In "The Tapir's Morning Bath," journalist Elizabeth Royte follows field biologists into the rain forest with a similar question: Other people, after all, do not feel compelled to sit up all night being bitten by mosquitoes, ticks, and chiggers. Why do these? The Panama Canal is made up of a channel leading inland from each coast, joined by an immense manmade lake that covers what was once a rain forest. Numerous islands dot the lake. In the 1920s, a group of foresighted scientists managed to have the largest, Barro Colorado, with its nearly intact tropical forest, set aside as a scientific preserve.In these pages, the present-day researchers of Barro Colorado spring vividly to life. Royte follows a young biologist from UC Berkeley, as the biologist follows a troop of spider monkeys.Studying monkeys like this entails long days of trailing the agile little creatures as they skitter through the treetops, clambering easily from branch to branch. For an earth-bound researcher, keeping up with the troop entails scrambling up steep ravines, pushing through tangled undergrowth, and skidding down hillsides slick with rain. The early weeks are especially frustrating, as distrustful monkeys shy away from the interloper.Royte, a New York journalist, is as much an interloper on the island as this scientist is among the troop of monkeys. The scientists, after all, have paid their dues to get here. They have spent years in graduate school, and they reach Barro Colorado only after their laboriously planned studies survive rigorous review to be selected for funding.But Royte ingratiates herself by offering to help. On the island, these scientists work long hours, and conversation can be larded with arcane jargon incomprehensible to an outsider. She's willing to wade through this - and the muck of mangrove swamps - to hang insect traps on branches and sit on the forest floor counting the number of leaf-cutter ants that march past.As they whiz across the lake in a Boston whaler, Royte is determined to pursue her subject at full throttle, even as the distinguished biologist perched in the bow tries to net moths without falling overboard. He shares his excitement about the natural world in all its magnificent complexity.For instance, he tells her, urania moths migrate annually. Some years, however, only a few hundred appear. Other years, several hundred million moths fly past the island. No one knows where they come from or where they are bound. In Royte's retelling, scientific enthusiasm is infectious. Soon we, too, want

An eye opener, entertaining and informative

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Elizabeth Royte successfully outlines the mysteries of the tropical rainforest and the plenty of questions it still harbors. A layman who is overwhelmed by the abundance of species gets a glimpse of an understanding of biodiversity and its interdependencies. For me it was impressive how Royte narrows down that each living being is part of that big wonder called nature. Like in a waterfall she is coming down 3 levels from general questions raised by Charles Darwin and S.T.R.I. founder's spirit to the emphatically described individual projects of the scientists on BCI. By watching the scientists at their work in a first place she finally learns that she can not remain out of the loop, but is herself a part of the permanent cycle of life. I was lucky enough to visit BCI for a couple of days only, but immediately felt a deep affection and rememberance during reading. This great book has the potential to make researcher's work more transparent und thus more popular and at the end of the day to have people treating nature with more respect.

I loved it

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

I absolutely loved every page of this book. As a field biologist who's spent time in remote rainforest field stations, I can say that she very accurately portrays many of the ups, downs and quirks of station life. Not only that, but she gives very honest descriptions of many aspects that biologists aren't as open to acknowledge (like the competitiveness and one-upmanship in wildlife viewing). The only down point in my opinion, is that many of the scientific names are misspelled, which detracts a bit of seriousness from other information she gives. Then again, I am one of those "peculiar" rainforest biologists, so maybe I take it too personally *grin*I also very much enjoyed her views on conservation and scientific research. Once again, she presents things from a different angle, with refreshing honesty and bluntness that is often missing in books written by biologists.I would not hesitate for a second to recommend this book!!

Island Passions, Mostly for Science

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

In a lake in Panama sits a six square mile island, Barro Colorado, and there are permanent research and living facilities there which have made the island one of the best-studied patches of rainforest in the world. A wonderful book, _The Tapir's Morning Bath: Mysteries of the Tropical Rain Forest and the Scientists Who Are Trying to Solve Them_ (Houghton Mifflin) memorably shows what the scientists are up to. Elizabeth Royte is a journalist, not a naturalist, but she was not just taking notes but taking part. She ingratiated herself into the society of strange eggheads who loved fieldwork by simply making herself available as an extra pair of untrained but willing hands. Because of this we get to follow her on all sorts of recondite forays to coax the jungle to give up its secrets. She follows spider monkeys in order to catch their feces, which she bags so that they can be analyzed for hormones. She climbs out branches to hang insect traps, and counts ants. She drives a Boston whaler zooming around the lake so that a biologist perilously hanging off the front can net migrating moths, and she learns to sex the moths by squeezing their thoraces. She triangulates to find out where bats fly around in the dark. She climbs trees to help monitor the behavior of creeping vines that modify the forest. At one point, a newcomer naturalist comes into Royte's room, mistakenly thinking she has found a fellow naturalist: "Oh, hi. Hi. Do you happen to have a syringe smaller than 1 cc? I'm trying to inject some solution into a butterfly's ear canal and what I have is way too big." Royte is excited about all these tasks, and her enthusiasm is on every page of her book. In addition, she has humorous descriptions of the men and women working on the island, but playing as well, with Ultimate Frisbee one of the least controversial amusements. But it is their work that makes the book. One of them explains that if he were intent on conservation, he'd be doing other work to promote it directly, and that he is attempting something like pure thought: "I'm setting up this experiment as an exercise in thinking. I don't want a utilitarian reason for everything. Why do we need art? I feel the same way about basic science: It's good for us."Reading Royte's book is good for us, too. There is a wide array of scientific information presented here, and plenty of good humor, raconteurship, and insight into how science is done and what makes scientists do it. It is also a deeply personal document, as during the year Royte married (to someone back in the States), became pregnant, and found that her reflections on nature and on evolution were deepened by the embryo growing with her. This is a surprisingly moving book about scientific endeavor and the solving of puzzles within and puzzles without.

Highly organized, thoughtful and fascinating

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Collecting monkey dung, triangulating bat flights, counting liana vines, sorting the trash dumps of leaf cutter ants, enduring chigger bites, a hundred different species of cockroaches, torrential rains and suffocating heat, Elizabeth Royte occasionally finds herself wondering what the point of it all is.For her first book, "The Tapir's Morning Bath," Royte, a journalist, spent most of a year in the rainforest field station on Barro Colorado Island, located in Gatun Lake, which makes up the midsection of the Panama Canal. Established by an American entomologist in 1923, the station is considered the epitome of luxury for field workers: labs with modern equipment, hot water, staff-cooked meals, even a lounge with beer.Diversity in the tropics is greater and more complex than anywhere else in the world and scientists have long asked why. Whether measuring water movement through the forest or calculating how far male frogs travel to sing in a group, each piece of knowledge raises a dozen new questions.Acting as an unofficial field assistant, Royte accompanied many of the scientists on their forest rounds. Personalities emerge as she observes the forest with them, shares their frustrations and triumphs and joins in the evening social life.Most are starting out in their fields; doctoral candidates or post-docs and their research is narrowly focused. Bret, trying to prove that his tent-making bats construct their temporary shelters in order to reduce feeding commutes, finds himself distracted by other cost-benefit examples and ponders an evolutionary theory of trade-offs which eventually extends to include a triangulation between youthful vigor, cancer and aging. Collecting vital statistics on spiny rats, Paul is a cog in a larger study of limitation factors on rodent population density. Chrissy collects spider monkey dung (for hormone analysis) in hopes of being the first scientist to correlate the sexual behavior of female spider monkeys with changes in ovarian cycle. The work is often tedious and physically demanding."Bret's voice sang out through the dark. 'Do you have those little white flies up there? Taking small bites of your flesh?'" 'Yup,' I answered, examining two dots of blood on my arm. 'When you turn on your light do you get little cockroaches crashing into your face?' "Royte, sometimes as discouraged as her study animals (the people), asks why, when the rain forest itself is endangered, money and time should be spent on such arcane pursuits. As her time at the station grows, her answer expands.Starting out, she sees each of these narrow studies as puzzle pieces in a larger picture, extending from the station's founding to well into the future and, in keeping with this view, she places current research projects in context with the people and discoveries that came before. As time goes on Royte sees how often an apparently pointless census of liana vines or canopy insects can provide insight into some marvel of nature - symbiotic relationsh