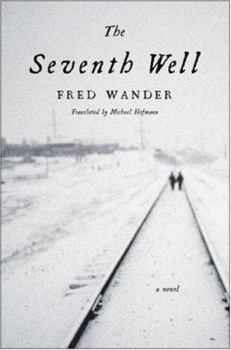

The Seventh Well

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

He grew up on the street, a high school dropout. In 1938 he left his mother and sister behind in Vienna and fled on foot to France, where later he was put on a train to Auschwitz. Transported from... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0393065383

ISBN13:9780393065381

Release Date:December 2007

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:176 Pages

Weight:0.55 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.9" x 8.3"

Related Subjects

Contemporary Education & Reference Fiction Genre Fiction Historical Literary Literature & FictionCustomer Reviews

3 ratings

beautiful, lyrical descriptions of wasteland and horror

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

There is such an incongruity to this book: beautiful, lyrical descriptions of wasteland and horror; characters that come to life for the reader as they head towards death, or are even already dead by the time Fred Wander discovers them (the dead man in the children's barracks); feral children whose instincts are honed to survival but whose minds cannot comprehend hope; sadness and cruelty; scorn and fellowship; the will and unimaginable capacity to survive, juxtaposed with the deaths that come about because of something inside that betrays (Tadeusz Moll; those who answered the final order to death as the Allies advanced toward Buchenwald). This ought to be a book that everyone reads along with Victor Frankl's "Man's Search for Meaning."

"You will become transparent, like a well yourself..." *

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Some books are easy to review. Fred Wander's The Seventh Well isn't one of them. This is meant as an accolade, not a criticism. Wander (born Fritz Rosenblatt; he changed his name in 1950) was a Viennese Jew who was interned by the Nazis in 1939, when he was 22 years old. He managed to escape into Switzerland (the internment camp was in France), but was sent back to spend the next six years in one camp after another. He was eventually transported to Auschwitz and endured the forced march to Buchenwald in the war's final days. His ordeal came to an end in April 1945 when the Allies liberated the camp. The rest of his family wasn't so fortunate. Wander calls The Seventh Well a novel, but I suspect it's so in the same way that Eli Wiesel's Night is: more autobiographical than contrived. In it, Wander provides us with 12 different stories about life in the camps. The chapters aren't offered in any sort of chronological order. They jump from Auschwitz, to the Buchenwald march, to flashbacks about life in French internment camps, back to the march. This atemporal presentation is entirely appropriate, because Wander isn't telling a history so much as groping for a series of tales that gesture at truths about humanity. It's no accident that the first chapter is entitled "How to Tell a Story," and centers on Mendel Teichmann, the man who taught Wander how to observe a situation and describe it in such a way as to capture its deep significance. And that's precisely what Wander does in his stories. The reason the book is hard to review is that each of the stories and each of the stories' characters cry out for individual scrutiny. There's Mendel Teichmann himself, the tzaddik, the magician, the magical story-teller; Zubitsch, who quotes Baudelaire's "Litanies of Satan"; Pechmann, who makes music with five drumming fingers; Meir Bernstein, the rich farmer, who in his final moments once again sees his lost family (p. 45); Pepe the Frenchman, the rebel; Tadeusz Moll, the atheist hasid, whose hanging provides Wander with the opportunity to reflect, poignantly, on the preciousness--and fragility--of life (pp. 122-28); and Joschko and Naftali, two children, brothers, who rekindle hope in Wander. Except for the two brothers, all the characters in Wander's stories perish. How does one accurately summarize their miseries, their hopes, their dignities, their martyrdom, in a review? A second reason why The Seventh Well is difficult to review is that the beauty of the language with which Wander describes the camps' horrors is sometimes almost too much to bear. Here's a description, from one of the Auschwitz to Buchenwald march stories (p. 49): "...evening is drawing in, milky white fogs are dotted about on the slopes and over the forest, a swarm of black crows flies up almost noiselessly, the air is damp. Someone has brought along a piece of canvas, the size of a blanket. Under it lie some twenty men, pressed together like herrings...All around

A View From the Barracks

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

How would you react if you were taken away from everyone and everything you knew and placed in a 'level of hell' that you didn't know could exist? How would you live day-to-day in a section of Dante's Inferno? That is what Fred Wander did for six years (1939 through 1945) while being moved from camp to camp (twenty in all) and finally being 'death marched' to Buchenwald where he was liberated by the American forces. What would be your explanation, not of why so many died, but of how you managed to survive? What would you remember? What would you take from the experience? Wander has given us the stories of individuals (all who later died) an how their lives gave his meaning. Stalin said, "the death of one man is a tragedy, the death of a million is a statistic". The number is too large to get into any kind of perspective. It's only when you look at the actual people, that you can put it into any meaningful place. One of the most striking symbols of the stories is that only the inmates have names and identities, the guards and workers are referred to only as 'jackboots'. They are uninteresting and interchangeable, they are just murderers and sadists, without any humanity. They are to be endured and fooled, and in some cases made the butt of jokes. But they are at all times, un-human.