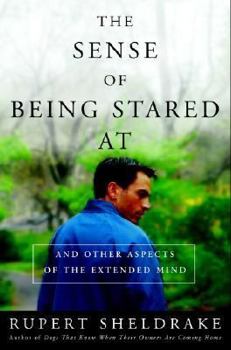

The Sense of Being Stared At: And Other Aspects of the Extended Mind

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Most of us know it well-the almost physical sensation that we are the object of someone's attention. Is the feeling all in our head? And what about related phenomena, such as telepathy and premonitions? Are they merely subjective beliefs? In The Sense of Being Stared At , renowned biologist Rupert Sheldrake explores the intricacies of the mind and discovers that our perceptive abilities are stronger than many of us could have imagined. Despite a traditional...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:060960807X

ISBN13:9780609608074

Release Date:March 2003

Publisher:Harmony

Length:384 Pages

Weight:1.33 lbs.

Dimensions:9.5" x 1.3" x 6.5"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Engaging stuff!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

As ever with topics of this sort, opinions tend to be polarised. Sheldrake's supporters tend to be 'up-beat' about his ideas, the sceptics - well, they'll just have to remain sceptical. If you haven't read this book - it is certainly worth looking at. For his own part, Sheldrake claims nothing - that is not already there, waiting to be acknowledged.He would be the happiest of all, if you discovered the basic truth of what he is saying, in your own experience, without pre-meditation. It strikes me that many people are predisposed to recognise or experience - what Sheldrake is getting at. In common parlance, it used to be called 'sixth sense' - with a kind of tacit understanding that it is more marked, in some people. The title of this book (The Sense of Being Stared At) - was selected because it is a sensation which almost all of us have felt, at some time. For any perceptive person, it is probably a daily occurrence (not to be confounded with paranoia, owing to a sense of shyness). Needless to say, the obvious way to 'test' the theory - is to tackle it in the active, rather than passive sense. Try staring at someone's back on the tube or bus, and see how long it takes before they turn their heads, in the direction of the gaze. Eight times out of ten, it 'works' within 90 seconds. The strange thing, is that it also works, if you focus on a person's image reflected in a train/bus window, the curious thing being that they look in the direction of the gaze, as mediated by the reflection. It is as if they pick up a node of energy. Of course, the whole point here, is that if minds operates with 'fields' - that there is kind of 'extended mind,' it has all sorts of dimensions, ramifications and implications. It was nice to hear one reviewer saying that Sheldrake's book had changed him, and that he'd decided to be kinder to other people. The 'sense of being stared at' is simply a test case. Sheldrake has extended his experiments to the animal kingdom, especially the inter-action or rapport between pets and owners. There may be limitations to the 'biological' bases that Sheldrake uses to justify his experiments, not least because the powers or energies he is dealing with seem to be psychic, or psycho-physical, rather than physical. Still, I object to the remarks of certain reviewers, who suggest that there is an element of academic posing in Sheldrake's work. Luckly, I had a chance to meet Sheldrake last year - at the British Library. He struck me as a modest man, unpretentious, genuinely curious about life and its mysteries. He shew videos in the lecture theatre at the B.L., giving ample illustration to his theories -about pets who know when their owners are returning home, even when separated by hundreds of miles. An Australian friend of mine, who had once endeavoured to educate Aborigines in the ways of the white man, returned from Ayer's Rock, totally changed in outlook, after discovering that the Aborigines invariably knew - days in advanc

Science at its very best

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Sheldrake's genius is taking commonly reported tales of human and animal abilities that challenge accepted scientific wisdom and developing simple ways of testing those claims under scientifically valid conditions. As with any series of experiments, especially those investigating controversial topics, they gradually evolve into ever-more sophisticated designs to eliminate possible flaws. Sheldrake has done this for the "feeling of being stared at," and the evidence he and others have amassed is persuasive, if reviewed without prejudice.I do not agree with his theoretical explanation for the "staring effect." In Sheldrake's view it suggests a mind that literally extends through space. I think there may be other explanations that better fit the data. But I heartily applaud his proposal of such a theory. Great advancements in science always encounter initial hosility and knee-jerk dismissals because they run counter to accepted wisdom. But without scientific mavericks unsettling the dogma of existing theories, science would rapidly congeal into religion. Indeed, for some hyper-rationalists, "scientism" is already such a religion, with its own set of doctrines, saints, and blasphemers. Sheldrake is a living reminder that by applying conventional scientific methods to unconventional ideas one can sometimes seriously challenge prevailing dogmas. Sheldrake's research and books, including this one, is science at its cutting-edge best.

Sheldrake Presses On

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

In The Sense Of Being Stared At Rupert Sheldrake publishes more results of investigations announced in Seven Experiments That Could Change The World (1994). His New Science of Life (1981), in which "morphogenetic fields" function as the organizing primal material principle in a novel theory of evolution, promotes the idea of an oak seed developing into an oak tree (rather than into something completely different) out of mere habit. Thus Sheldrake endows the material world with an intelligence that keeps alive by projecting memories of itself into the future, claiming by the same token that the laws of nature are neither eternal nor immutable but rather acquired and in constant process of adaptation. Sheldrake's tenets hit the world of the hard sciences like a bombshell, and he has been busy providing proof for his thesis of interwoven memory fields ever since. Thus he became involved with pets and others animals, subjects he is particularly fond of since their perceptions are incorruptible. Dogs That Know When Their Owners Are Coming Home (1998) lead him to a series of other applications, where a projection of the senses into the future was involved. The mental sensor seemingly responsible for these feats he calls the "seventh sense" or "extended mind". The result of his latest research does not only encompass a discussion of telepathy but also of the human eye and its unchartered perceptions. Analogous to Albert Hofmann?s sender-receptor conception of reality, the exchange of energy and information reaching and leaving the eye are paramount to visual activity. Or why would most of us feel when we are being stared at? Some further questions are: do you know who it is when your phone rings? Do you wake up before your alarm clock sounds? Are you or your pets prone to forebodings? Are you a woman who starts lactating when her baby is about to cry for milk? What is a mental field? How does the mind send and receive mental impressions? There is no doubt that the traditional sciences fail to explain these experiences in a satisfactory manner. "Clues lie disregarded all around us," Sheldrake announces. Entertaining as always, he leads us to a telepathic parrot, introduces us to dogs, cats, horses and their owners as well as showing us many humans whose emotional bonds have unexpected side effects. The good news in all this: the phenomena discussed by the author are universal, and he makes good headway in demonstrating that Darwinists inhabit a racist victorian suburb rather than living on the 8 Mile of quantum reality. The bad news: it takes a long trip across the land of statistical probability for you and I to get there!

the so-called 'skeptics' look silly again

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Renegade biologist Rupert Sheldrake analyzes in depth an experience that many of us have had at some point - a strange compulsion to look up or behind, only to see someone staring intently at us. In his latest installment Sheldrake discusses a variety of anecdotal and experimental evidence that establishes the reality of the phenomenon, and attempts to explain it with his theory of the 'extended mind' - the idea that our minds are not confined to our brains, but may extend into our environment. Needless to say, Sheldrake's work is a challenge to scientific orthodoxy, making Sheldrake the modern equivalent of a heretic. Shortly after publication of his first book, Nature magazine, one of Britain's leading scientific periodicals, called it "the best candidate for burning there has been for many years." In an interview broadcast on BBC television in 1994, John Maddox, the former editor of Nature, said: "Sheldrake is putting forward magic instead of science, and that can be condemned in exactly the language that the Pope used to condemn Galileo, and for the same reason. It is heresy."However, Sheldrake follows an impeccable scientific approach. The writing in this book is very clear, and the evidence for the reality of the phenomenon is very impressive. The empirical sections of the book are the most persuasive. His theoretical explanations will likely generate the most controversy among those scientists and philosophers who are willing to drop their prejudice and concede the reality of the sense of being stared at. Sheldrake combines his theory of the 'extended mind' with his idea of morphic fields - regions of influence not currently recognized by mainstream physics, but (it is argued) necessary to explain the growth and regeneration of organisms. Those readers interested in this will want to read Sheldrake's best and most important work, The Presence of the Past.Where this explanation of ESP in terms of fields may falter is that all of the other fields recognized by physics decline with distance. Parapsychology experiments have demonstrated that ESP is not affected by distance, or by shielding of any sort. Explanations of ESP in terms of electromagnetic fields, for example, have been convincingly falsified by such experiments. Morphic fields, if they exist, must have very different properties from the known fields if they are to explain ESP. Some physicists feel that the non-local quantum mechanical effects that have been corroborated in physics experiments may more plausibly explain ESP. If there is any shortcoming to this book, it is that related profound issues - such as the mind/body problem or the implications of quantum mechanics - are dealt with only briefly. Again, this is not true of Sheldrake's masterwork, The Presence of the Past.So, readers who wish to delve more deeply into Sheldrake's theories know where to look. Sheldrake is a bold scientist, one who never lets convention or dogma interfere with his explorations.As Sheldrake writes

Clear and concise explanation of "psychic" phenomena

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Dr. Sheldrake is no "paranormalist." He's a highly respected researcher and theorist, a retired professor of cell biology at Cambridge University, who investigates unexplained powers of the mind because they can tell us a great deal about the nature of mentality. He not only reveals irrefutable statistical evidence for the existence of telepathy, remote viewing, precognition, and the power of attention, but more importantly his explanation of these phenomena roots them firmly in the biological sciences. He refers to them collectively as the "7th sense," after the five senses and the lesser-known ability of certain animals to sense electromagnetic fields. The field concept, which began in physics and spread to biology in the 1920s, is essential to Sheldrake's theory. "Morphogenetic fields" are invoked by developmental biologists to account for the curious ability of cells in a given organism to perform different tasks even though they all have identical DNA. Why does one area of an embryo form into an arm, for instance, while another area forms into a heart? Because cells fall under the influence of different "form-giving" fields. Most biologists assume that these fields, which are essential in describing organic development, will one day be explained according to genes. Sheldrake is not the only theorist who disagrees and claims that these fields are as real as gravitational or magnetic fields. What we call the "mind" may simply be the morphogenetic field associated with the brain. According to this view, sense organs involve extended fields that embrace the object of perception. This is why people can tell when they're being stared at. While this book is not the first to provide overwhelming evidence of the 7th sense (see Dean Radin's The Conscious Universe), it is the first to place this material within the context of an explanatory hypothesis. The importance of this book cannot be overstated.