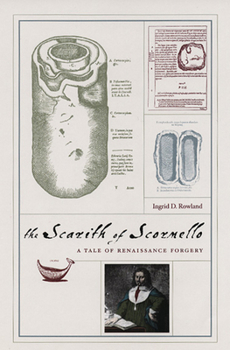

The Scarith of Scornello: A Tale of Renaissance Forgery

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A precocious teenager, bored with life at his family's Tuscan villa Scornello, Curzio Inghirami staged perhaps the most outlandish prank of the seventeenth century. Born in the age of Galileo to an illustrious family with ties to the Medici, and thus an educated and privileged young man, Curzio concocted a wild scheme that would in the end catch the attention of the Vatican and scandalize all of Rome. As recounted here with relish by Ingrid...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0226730360

ISBN13:9780226730363

Release Date:December 2004

Publisher:University of Chicago Press

Length:192 Pages

Weight:0.90 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 5.9" x 8.3"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

An academic, but well-told, account of an historical hoax

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

THE SCARITH OF SCORNELLO, by Ingrid Rowland, is the story of a seventeenth-century hoax, perpetrated in Tuscany. The story makes me wonder whether and how various twentieth-century hoaxes will be remembered three centuries from now - such matters as Clifford Irving's authorized biography of Howard Hughes or the "Hitler Diaries" that "Das Stern" published. My guess is that most of them will have faded into utter oblivion, unless and until a future Rowland comes along to restore them to historical consciousness for a generation or so. "Scarith" was the word given to small capsules of mud and hair first found in 1634 by 19-year-old Curzio Inghirami on his family's estate near the town of Volterra in a part of the Duchy of Tuscany that two millennia before had been an Etruscan stronghold. Inside the scarith (the same form of word is used for both the singular and plural) were pieces of linen rag paper bearing writings in both Etruscan and Latin from, purportedly, an Etruscan priest named Prospero of Fiesole who secreted them for posterity just before succumbing to vindictive Roman imperialism around 62 B.C. Taken cumulatively, the papers of the scarith revealed a more glorious, sophisticated, and noble Etruria than previously was commonly accepted. They also were startlingly prophetic about several matters, including the coming of the Messiah "after whom the years shall be numbered". As some immediately suspected, it was all a hoax, something that soon became clear to all with eyes to see, unblinkered by some ancillary agenda. To me, the most remarkable things about the hoax were these: first, it was the work of a 19-year-old (although Curzio Inghirami then had to devote the rest of his life to perpetuating the hoax); second, he did it not so much for personal gain as for civic gain (burnishing the image of his native Volterra); and third, the fraud was so sloppily executed. Indeed, from the book it appears that the only reason it ever "got legs" and became a minor cause célèbre was that it was seized upon as yet another issue in the political and cultural power struggle between Rome and Tuscany, a power struggle that just one year before the discovery of the first scarith had resulted in the inquisition of Galileo and his recantation of a heliocentric universe. The story is well-told by Rowland, but the plain fact of the matter is that it is a rather erudite story to which the ivy of the tower still is clinging. I found myself wondering whether in this instance I had wandered too far down the backwaters of history. The book is primarily for those who enjoy academic historical arcana. If you have a nagging suspicion that perhaps THE SCARITH OF SCORNELLO is a little too abstruse or scholarly for you, you probably should trust your instincts and give the book a pass.

Intellectual Fraud ...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

... is nothing new. It isn't an invention of today's disingenuous deniers of anthropogenic climate change. It was widespread and tremendously significant in the early centuries of Christianity, both in the 'interpretations' copyists intruded into the four canonic gospels and in outright forgeries like the influential writings of the Pseudo-Dionysius. But the boundaries between malicious fraud, purposeful fiction, and practical joke have never been absolute, and in Renaissance Italy, such boundaries were non-existent. The remarkable forgery reported in this study, committed by a clever teenager in 17th C Tuscany, had elements of all three, beginning perhaps as a 'beffa' - a satirical jest - flavored with chauvinistic purpose, and escaping the perpetrator's control to become a significant cultural conflict. "Scornello" is a place, the seat of a powerful Tuscan family, the Inghirami. "Scarith" is the word invented by Curzio Inghirami to designate the "time capsules" containing the messages to the future of the fictitious Etruscan priest Prospero, which Curzio and his sister planted around Scornello and then later claimed to 'discover' by accident. Their forgery wasn't very well executed, but the techniques of forensic archaeology were not very well developed in Renaissance Italy either. Skeptics leaped on Curzio's claims almost immediately, relying chiefly on textual clues in the young Volterran's Latin syntax. From our lofty knowledge of the detective's craft, it seems almost comical that none of the skeptics thought to compare Curzio's handwriting to Prospero's purported script. Even more inexplicable: the first skeptics based their doubts on the fact that the scarith were written on paper, while all classical Romam historians ahd asserted that the Etruscans wrote their annals on linen cloth; decades passed before anyone noted that Curzio's paper carried a watermark from a local Tuscan paper mill of his era. The hoax, amazingly, became an international 'news item' and provoked fierce political confrontations between Tuscany and the Papacy. Ironically, though Curzio/Prospero's annals of Etruscan history were outright humbug, the refutation of the scarith stimulated historical and archaeological interest in ancient Etruria that eventuated in important discoveries. Curzio himself never seems to have suffered any opprobrium for his hoaxing; he remained a significant personage among the leaders of Volterra until his death in his 40s, and his penchant for forgery continued. The civic archives of Volterra turn out to be replete with Curzio's fabrications. Author Ingrid Rowland is a skillful story teller, and "The Scarith of Scornello" makes quite a delightful 'detective novel'. Fashion is Truth, you know -- both being constrained by relativism -- and the study of history is as subject to shifts of fashion as the cleavage or hemlines of women's garments. The "Fashion" of historical writing in OUR times is this sort of macro-lens study of ordinary lives

An engaging account of a ridiculous archaeological fraud

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

I have no particular interest in archaeology, but this true account of a 17th century Etruscan archaeology forgery kept me completely engaged until I finished it. The author makes it quite clear almost from the first chapter that the the find is forgery, so there's little mystery to the book. But the controversy and politics surrounding the forgery, involving church leaders, nobility, and intellectuals across Europe make it clear that the concern about the genluineness of the archaeology find was secondary to everyone's concern about their own careers, reputations, and public images.

An Ancient and Amusing Forgery

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

As right-thinking citizens, we all abhor crime. We think that the guy who forges a signature on someone else's check is a contemptible scoundrel. But forgers who do such things as paint masterpieces wonderfully well in the style of someone else, or forgers who write diaries of, say, Howard Hughes or Hitler, those we may find to be attractive scoundrels. They pull a prank and get away with it, or away enough with it that experts are fooled until other experts force the truth upon them. In _The Scarith of Scornello: A Tale of Renaissance Forgery_ (University of Chicago Press), Ingrid D. Rowland has written about a very peculiar forgery of the seventeenth century. It is a tiny piece of history, long overlooked, but the forger had his fun, and had a bit of influence for his times. Rowland's work is a serious piece of erudite scholarship, but the scoundrelism and the reactions to it make for fascinating reading. In November 1634, Curzio Inghirami, nineteen years old, near his family's villa Scornello found a scarith, a capsule of mud containing peculiar documents written on paper in Latin and in Etruscan, the ancient language of the region that had yet to be deciphered. He eventually found over 200 of these, purporting to be documents from 64 BCE, which among other things, put a Tuscan spin on the Catline revolt against Rome, showed that Noah had founded the nearby ancient city of Volterra, and predicted the arrival of the Messiah. Curzio's book _Ethruscarum Antiquitatum Fragmenta_ appeared in 1636. Curzio's family ensured that the book was simply gorgeous, full of woodcuts and copperplate engravings on good quality paper. The book was designed to convince anyone who merely glimpsed at it of the truth of its contents. Academics based in Rome who descended upon it showed the forgery to be obvious. The foremost objection was that the scarith were written on paper, while Etruscans knew nothing about paper; they wrote on linen cloth. (Long after the controversy had died away, a commercial watermark was even found on them.) Curzio had indeed arranged the forgery, but it was so strongly criticized and defended, he could not back down. The battle was on a higher plane as well. It was only a year before the scarith were discovered that Galileo, a Tuscan, had been forced to recant his model of the universe with the sun at the center. The Pope was eager to put down this new bid for Tuscan pride, and Florence was just as eager to regain the intellectual reputation besmirched by Galileo's conviction and house arrest. Rowland thinks that Curzio was participating in the practical joke, such an art form in Tuscany that it has its own name, beffa. His original scarith might be seen as preposterous parodies, but he did have a genuine interest in Etruscan objects and culture, an interest promoted by patriotism for his homeland. When his fellow citizens and family took up his cause, perhaps there was no way that he could back down. He was destine