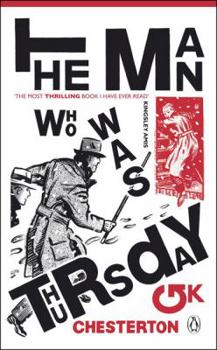

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

G.K. Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday is a thrilling novel of deception, subterfuge, double-crossing and secret identities, and this Penguin Classics edition is edited with an introduction by... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0141033754

ISBN13:9780141033754

Release Date:May 2008

Publisher:Penguin Group

Length:209 Pages

Weight:0.35 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 4.4" x 7.0"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

This one kept me up late

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

This was my first reading of Chesterton's fiction, and I couldn't put it down. Chesterton had a keen mind and a gift with words. If you're trying to decide whether to try one of his books, this would be a great place to start- a mystery with a twist!

A nightmare?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

"The Man Who was Thursday" is a fantastic, bizarre puzzle that defies attempts at explanation or description. On the surface, it is a spy story about anarchistic terrorists with elements of suspense and paranoia; as you dig a little deeper, a black comedy emerges; peeling back a few more layers reveals a philosophical underbelly; and it all ends in an uproariously enigmatic denouement worthy of Lewis Carroll. If the book is, as its subtitle indicates, a nightmare, we all should hope to have dreams as sweet as this.The hero, Gabriel Syme, is a poet-detective (yes, seriously) who works for a special branch of Scotland Yard dedicated to apprehending "intellectual" criminals, particularly anarchists, because they tend to be the most subversive and therefore the most dangerous. By operating undercover as a poet-anarchist, Syme manages to infiltrate the seven-member Central Anarchist Council, who alias themselves using the names of the days of the week, and fills the vacant slot of "Thursday." The Council's main directive is to cast the world into chaos by assassinating heads of state, and their current plan, as masterminded by their president, "Sunday," is to bomb the upcoming meeting of the Russian Czar and the French president in Paris.It is, of course, up to Syme/Thursday, who is always at risk of being exposed as a policeman, to put a stop to this nefarious scheme, to which there is naturally more than meets the eye. As the plot unfolds, it breaks down (or builds up) into an indescribably wild farce; Syme's mission turns into a picaresque adventure of disguises, a swordfight, and several chases -- involving horses, cars, an elephant, and a hot-air balloon. At the end of the book, a surprise is waiting; a strange detachment from everything that has preceded it, which slyly lets the reader in on its symbolic joke. If not for its relentlessly silly tone and idiosyncratic resolution, "The Man Who was Thursday" could be a perfect sister novel to Joseph Conrad's "The Secret Agent."Like fellow British wits Dickens, Wodehouse, and Waugh, Chesterton is that rare sort of writer who is skilled in combining breathtaking narrative with irreverent and intelligent comedy and whose prose is as poetical as it is humorous. The fact that Kingsley Amis called this novel the "most thrilling" book he'd ever read speaks volumes.

Kind of weird but worth it

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

I have just finished this book and have to say, I concur with Kingsley Amis (writer of the introduction) who said that it was the "most thrilling book he has ever read." Chesterton weaves together a combination detective story, wierd dream ("Nightmare" as he says on his cover page), and social commentary. It's certainly not an apologetic book (as C.S. Lewis said, one can't always be defending the faith, sometimes one has to encourage those already converted), but elements of Christianity do come through (especially Chesterton's sensible view that your faith should affect every area of your life and outlook to the world).The hero, Symes (who is called Thursday) is a detective and a Christian who provokes an anarchist and infiltrates a world-wide underground anarchist society. From there, I won't spoil the story but there are many adventures, twists, and turns. This part I thought very well written. Every new discovery Symes makes literally had me on the edge of my seat. Things become more and more bizarre (right in line with Chesterton's own description of his book as a "Nightmare") until a very bizarre ending that I confess I have still not fully absorbed.There is a great deal of symbolism and allegory in the book, which is not clear until at least a third of the way through the book. In this way, the book is similar to C.S. Lewis's book "That Hideous Strength" (the third book in his space trilogy that includes "Perelandra"). Like Lewis's book, "Thursday" starts off very realistic (although with some hints of the bizarre twists to come) and gets more and more strange as the book goes on.Two things that will be helpful to understanding much of the symbolism:(1) Read the afterword at the end of the book by Chesterton. Unlike Amis's introduction, I wouldn't read it before you start reading the book. I'd recommend reading it after about a third of the book, perhaps right around the time the Pole is "unmasked" (that is, around chapter 6).(2) Also helpful is Martin Gardner's commentary on the book. There is another edition of the book that has Gardner's comments, but the most important parts of his commentary are available on the Internet (just search ye shall find them). This lays out the symbolism in more detail than the former, so if you want to figure it out for yourself don't read this until the end of the book.Finally, after you read through the book once, think about it and read comments such as Gardner's, then go back and read it again. As Amis says in his introduction, you can read this book many times and get new things out of it every time.

Intellectual autobiography, dressed in fantasy

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Having recently read this book again, I have to say that it made considerably more sense this time than when I read it in my teens. In fact the symbolism, while superbly thought-out, was, I thought, made too explicit at several points, when characters simply say outright what all of it means. I still loved it. It is exalted above mere autobiography by Chesterton's light spirit and vigorous fantasy, but even if it were merely autobiography, it would be a treasure, fully the equal of "The Education of Henry Adams."For those to whom its nature as intellectual autobiography is not clear, I advise a closer reading of the poem to E.C. Bentley that prefaces the story. The poem speaks of the intellectual chaos of their shared youth and the wisdom ("touching the root" as he puts it) that was created from it. The creation of wisdom from chaos explains Chesterton's use of symbols from Genesis, also a story of creation from chaos. Chesterton in his youth was intellectually volatile, by his own account descending into solipsism. The six days of creation represent different stages of his own intellect; Professor de Worms, for example, is solipsism, Gogol socialism (which Chesterton never took seriously), Bull materialism, and so on. Just as each is revealed to be an agent of order, so Chesterton found that as he confronted each philosophy it was disarmed, and that in doing so he moved ever closer to wisdom, which is faith in God. Sunday is perhaps a bizarre symbol for God, but further reading in Chesterton (or indeed the Bible, especially Job, as was pointed out in the Ignatius collected edition) will show that all the most baroque and incomprehensible aspects of Sunday are the most literally orthodox.It's all dressed in an entertaining if sometimes confusing fantasy, but it should not be necessary to say that Chesterton did not actually advocate "thought police" any more than he advocated turning suburbs into armed, walled cities, as in his book "The Napoleon of Notting Hill." As to the review that considers the book "Dali in anarchist drag," I recommend that he read the preface in which Chesterton explodes that idea, which had already been advanced in his lifetime. Finally, all readers should re-read the first chapter of Genesis before beginning the book, to have the source of the symbolism fresh in the mind.

Finding a deeper meaning to an already deep book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

Upon finishing TMWWT, the general audience is left with a "what the devil" kind of feeling. But then he must re-read the section aptly titled "the accusuer." What infuriates many is Chesterton's jump from a detective story to something "metaphysical." The theme being developed is hardly metaphysical. It is the fundamental basis for Christian thought and perhaps a precursor to Objectivism (subtract the God). It is about the human struggle to defend one's beliefs from the onslaught of rampant relativism and general evil. It is the same task facing conservatives today. Particularly appealing was G.K's attack on intellectuals as well as his parody on the police. People who describe this as fascist, I think, are simply upset that G.K. puts the socialist at odds with the plebicite, which he truly is. But that is the genius of Chesterton