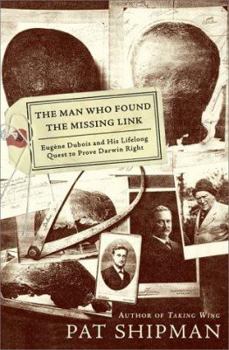

The Man Who Found the Missing Link: Eugine DuBois and His Lifelong Quest to Prove Darwin Right

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Born eighteen months after the first Neanderthal skeleton was found and a year before Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species , Eugene Dubois vowed to discover a powerful truth in Darwin's deceptively simple ideas. There is a link, he declared, a link as yet unknown, between apes and Man. It takes a brilliant writer to elucidate a brilliant mind, and Pat Shipman shines as never before. The Man Who Found the Missing Link is an irresistible tale...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:068485581X

ISBN13:9780684855813

Release Date:January 2001

Publisher:Simon & Schuster

Length:528 Pages

Weight:1.85 lbs.

Dimensions:1.5" x 6.4" x 9.6"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Great for all with an interest in paleoanthropology

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Shipman has done a spectactular job of chronicling the life of the man who many acclaim the father of modern paleoanthropology. This intrigiung man, Eugene Dubois, dedicated his life to a cause (elucidation of the link between humans and primates) with a passion not often found in scientific circles. I found the details regarding ED's personal interactions and relationships crucial to gaining insight into the persona and character of the man. He worked with a stern presence and perserverance that I found unbelievable. His dedication to his work really amazed me. In a sense you feel that he was destined to make such an earth-shattering discovery, but at the same time you can help but feel that he was also lucky. That is, many devote lifetimes to an investigative cause and come up empty handed or never live to see the fruits of his or her labor. I really enjoyed the book. As a scientist in another field (a paleoanthropology layperson at best), I found the book very informative and digestible. I did have to research some of the details to develop an understanding of some of the anthropologic principles and moreover the history of the discipline. It was a great learning experience. I like other books by Johanson and Leakey, but this one has a historical third person perspective that adds intrigue to the topic. Again, A great book.

good to learn more about dubois

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Many thanks to Pat Shipman for bringing alive this strange man who lurks around the edges of the story of evolution, jealously hiding his treasure trove of bones. He is one of those characters who always shows up, but you never had a chance to meet.Just as skilled paleontologists reconstruct long-dead animals from a bone here, a tooth there, Shipman resurrects Dubois from a note here, a letter there. Of course much of this we have to accept on faith: we have no more solid proof that Dubois's behavior in many cases was just as Shipman has recreated it. But without her leaps of judgment, this book would be very dull, very scanty reading. Parts of the book are slow as we examine the ins and outs of old controversies and theories, but this detail is important for us to understand Duboi's character and work. Slog on through, but remember that Dubois was kicking and screaming into his eighties, so the book does go on. Maybe just as well we did not digress into the Taung baby and other contemporary discoveries. I have read other books by Shipman, so it came as no surprise to me that the book was meticulously researched, informative, and enjoyable to read. However, I hope I never again have to read a book written almost entirely in the present tense. Shipman is a good enough author that she does not have to resort to such a tiresome gimmick to bring immediacy to her scenes. Professor Shipman, if you are out there in front of the computer screen, please keep typing, I am looking forward to your next book. But please do remember how interesting the tenses of the English language are.

Sepia Toned Portrait Charming

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

I recommend this book to anyone regardless of her or his interest in human anthropology. Shipman's portal to the science is well written and tinted with full details of family life. A three dimensional portrait of Eugene Dubois that Shipman has deftly produced in the manner of a Masterpiece Theatre episode. This flavors the science so it goes down like dutch chocolate. Now that I'm hooked on the science, I'm tackling her co-authored "Neandertals".

A great story, beautifully told, but with odd balance.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The sentences in this book have been so elegantly crafted that they flowed like a smooth running brook. Since my wife and I like to alternate reading chapters from anthropology adventure stories out loud to each other, we were captivated by the editorial polishing that allowed us to pick up speed with nary a fumble (except for the occasional technical, Dutch or Indonesian words). While we had expected rough and tumble science, we were pleasantly surprised by how much this one was about Eugene Dubois's human relationships and the ups and downs of his feelings. (Perhaps there is a sex difference among biographers that accounts for this.) The first half of the book describes Dubois's family and friends to the exclusion of much of his science, with somewhat of an opposite imbalance in the second half. For example, early on we gleaned from the occasional aside and bibliography (annoyingly given mostly in Dutch without an English translation) that he wrote several papers and a book on the evolution of the sun as discerned from studying the earth's geology. Unfortunately, the author does not tell her readers how or why he did this, or how much of his time this took up, or even what he hoped these efforts would accomplish for him, though we are told that he was achingly ambitious. Instead we find excruciating details of his relations with his family and friends, and how he traversed the flora and geography of Java. Eventually, he discovered Pithecanthropus erectus, the "missing link" between man and ape. Later, after Dubois and his family return to the Netherlands, we do get excellent blow-by- blow accounts of the scientific in-fighting as other fossils like Peking Man and other Java men are discovered that cause reinterpretation of his finds and provoke controversy about them (later they are relabeled Homo erectus). By then, despite ourselves, we were hooked on his family relations and so frustrated to suddenly be left hanging about what happened on that front. Shipman tells us how and why Dubois separated from his wife, but not explicitly why they got back together or how they get along after they did. While his children tragically die, or wander off, or or make bad marriages, we get little information about how he does end up with descendants. Even the scientific story has some inexplicable gaps. The big debate rages over the status of Java Man and Peking Man along with Neanderthal and other finds. Even Piltdown Man takes center stage at one point. But the debates over Taung Child and other discoveries in Africa are never mentioned. Did I miss something? We both came away feeling that the book got too long and instead of editing it down, section by section, a production decision was made to simply delete some of the chapters! Despite these glitches I learned a lot from this book. Dubois did more than find a great fossil. He wrote a great deal on encephalization quotients (i.e., the ratios of brain size to expected body size) anticipating much curr

Spotlight on an Obscure, Important Scientist

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Everyone knows that there is still religious (not scientific) opposition to the Theory of Evolution, but when it was unveiled, there was strong scientific opposition as well, which only decreased as more (and younger) scientists grew to accept the powerful explicatory capacities of the theory. The most unacceptable part of the theory was that humans themselves had evolved from some previous ape-like form. Scientific opposition to this idea started crumbling when the "Missing Link" between humans and their obviously non-human forebears was found. Eugéne Dubois was the man who found it, and his story has never been fully told. Now, in _The Man Who Found the Missing Link: Eugéne Dubois and His Lifelong Quest to Prove Darwin Right_ (Simon and Schuster), Pat Shipman has written an exciting biography of a neglected genius, and has given a narrative that tells how paleontology was done in his times, as well as how his ideas eventually became accepted within the scientific world.The word "lifelong" in the subtitle of the book is almost literally true. Inspired by learning about the Theory of Evolution as a boy, Dubois learned that transitional forms between ape-like creatures and humans were hypothesized but had not yet been found. The boy realized that finding such a specimen would be possibly the greatest scientific discovery ever, and astonishingly, he was convinced that he was going to be the one to do it. With this in mind, he entered medical school and engineered an assignment as a physician in the Dutch East Indies, for it was there his research told him the missing link would most likely be found. Shipman's account of the prospecting years is exciting. Dubois took his family to the islands, he survived cave-ins, malaria, and government neglect, and he identified thousands of mammalian fossils, including in 1891 a molar, skull, and thigh-bone of the missing link. His Java Man (which he classified as _Pithecanthropus erectus_) had a small brain, a flat forehead, and a leg made for upright walking. To Shipman's credit, she illuminates well the sadder aspects of the man and his subsequent story with equal detail. Dubois was brilliant and tenacious, but he experienced real betrayals in his scientific life that consumed him. He had a lifetime that was hard enough. His beloved father died while Dubois was prospecting in Java, and never learned of Dubois's spectacular success. When Dubois brought the specimens home, the reaction of his mother was, "But, boy, what use is it?" As the finder of the first link between humans and non-human ancestors, Dubois was necessarily the lightning rod for attacks from the clergy and the public. Also, the old-guard scientists who had not accepted evolution found or imagined reasons to disagree with Dubois's discoveries. He felt himself so ill-treated that he locked up his fabulous specimens for decades, provoking an international scientific protest when he would let no one else examine them.Shipman has