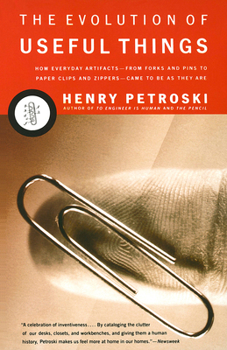

The Evolution of Useful Things: How Everyday Artifacts-From Forks and Pins to Paper Clips and Zippers-Came to Be as They Are.

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

How did the table fork acquire a fourth tine? What advantage does the Phillips-head screw have over its single-grooved predecessor? Why does the paper clip look the way it does? What makes Scotch tape Scotch?

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0679740392

ISBN13:9780679740391

Release Date:February 1994

Publisher:Vintage

Length:304 Pages

Weight:0.57 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.2" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

All about the context

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I found this book to be very illuminating in light of what I do (interaction design) and the books I have read recently on the latest in computational neuroeconomics, maninstream pattern recognotion theory, interaction design, visual design, industrial design, computer engineering, new marketing theory, and information design around complex systems. In fact, this book is almost a stake in the ground on how the manufacturing process, invention, and branding created the artifacts in our environment. Better than the Industrial Desig books I read 10 years ago. I think we would call these "case studies" and "use cases" in modern terminology. I mention all the fields above because every single one of them have an exact doppelganger in the past. This book is a brilliant look at process and can be used as a research tool when looking at why something like the iPod caught on and why almost everything that has been developed at MIT in recent history (except eInk) has never gained a foothold in popular American culture. In the face of the rise of "everyware" computing, it's adoption in places like Korea and Japan, and only limited use by the rich for personal security in the US, I would say this is a must read for contemporary designers, no matter what depth of complexity their task at hand. This book predates the web, making it very enlightening in light of user-centered design in recent years. This book looks at the relationship of genius design, corporate R+D, pop culture, the feedback loop for product innovation, and the adoption of standards around SIMPLE things. This means these case studies can be used to analyse the failures (and how failure breeds innovation, not "form follows function") of our complex information economy and embedded systems. Society has gone through it all before. And as projects become increasingly team based and open sourced (like Stanford's new d.school), just about anyone can find value in this book based within this context.

Hidden Depth

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

On the face of it, the Evolution of Useful Things simply lists fun trivia about familiar objects. Why does a fork have four tines and not two or three? What's a perfect paperclip? Is there such a thing? Who invented the zipper? How many things can you see on your desk right now? However the book gives us much more. Petroski uses a large number of concrete facts to present general laws of human thought and activity. The paper clip appeared because pins used to hold papers together made holes in them and could injure someone looking through files, but it took a while for it to reach the form we know today. We invent new things because we are dissatisfied when we find problems. Form follows not function, but failure. While small objects play the center role here, large machines such as locomotives and large projects such as bridges also come up. Petroski argues that for his concepts to be valid, they must apply to the great as well as the small and he shows that engineers design new bridges or tunnels by solving problems observed found while building other bridges and tunnels. The book's title is especially good. The evolution of man-made things differs fundamentally from the evolution of living things. Natural selection follows a mindless process of sifting through countless minute _random_ changes. Things, however, evolve through a different process of sifting through countless _intended_ changes (sometimes small, somtimes large) until something arises that works better than before. Petroski's writing does annoy me a little; he's got some really bad puns. For example he follows two different quotations of how to manufacture a needle with the phrase "there's more than one way to make a point." Another problem is that he repeats himself. For instance, he twice mentions Karl Marx's astonishment at finding 500 different kinds of hammers in a Birmingham factory. But the originality of his thesis far outweighs these minor flaws. Henry Petroski is a philosopher of engineering examining the question of why we invent things. He asks why we are always perfecting our inventions, why we are never satisfied with our tools as they are. His proposed answers in no small way explain much of the history of our rich living environment with its tens of thousands of useful things. Vincent Poirier, Tokyo

A Lucid Primer on Industrial Design for Everyday Folks

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

How does everyday discontent lead to material progres? Does form follow function? What are some common mistakes in patent writing? The Evolution of Everyday Objects, explores the hidden history of axes, spoons, paperclips, garbage bags,tin cans, and zippers for a general audience. Henry Petroski, a professor of industrial design at Duke University, also introduces unlikely heroes like Walter Hunt (the safety pin) Richard Drew (Scotch tape), and Jacob Rabinow (pick-proof lock) while celebrating the marvels of engineering and industrial design. This lucid primer weaves a weird and wonderful tale of techincal evolution and expanding consumerism. Petroski argues that disappointment with available choices inspires inventors, engineers, and industrial designers to continually expand our consumer choices. Form, contrary to rumors, follows failure. Edison's edict seems more apt than ever.Petroski focuses on the telling details behind both familiar success stories and the far more frequent failures of consumer objects and modern artifacts. Although this 288-page paperback lacks illustrations and might seem a bit repeative and/or simplistic to specialists, Petroski's book should appeal to aspiring inventors, engineering students, and curious readers seeking a better understanding of our modern consumer culture. You might even look at your cluttered desk, a crowded department store, and your crammed tool shed with more appreciation.

Looking for the perfect gift for the man who has everything?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

Here it is. I purchased this for my Dad, 79 years young. Finding anything for him, that he hasn't seen, heard or done is very difficult. Imagine my surprise when he sent me a note stating this was the BEST gift he'd received in a long time! I also bought him "to Engineer is Human..." ... same message! Both are super-duper gifts!

Great reading, just too repetitive

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

Petroski introduces some wonderful and introducing ideas about the develop and baroque-ing of ordinary objects, as well as illuminating the whole notion of "things" that seem self-evident after they were invented. Okay, the man needs an editor. Please, someone, convince him. His book The Pencil suffers from the same needless and enormous repetition. Both books could have been 1/2 to 1/3 of their sizes and been enormously improved. His saving grace is his solidity of research and his interesting ideas.