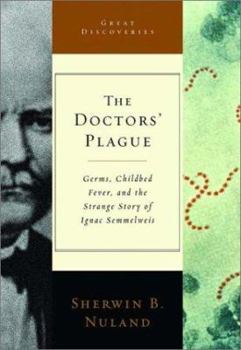

The Doctors' Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignac Semmelweis

(Part of the Great Discoveries Series)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Ignac Semmelweis is remebered for the now commonplace notion that must wash their hands before examining patients. In mid-19th century Vienna, however, this was a subversive idea. This is the revealing narrative of one of the key turning points in medical history.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0393052990

ISBN13:9780393052992

Release Date:October 2003

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:191 Pages

Weight:0.70 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.8" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The Cry and the Covenant redux

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Childbed fever (puerperal sepsis) was the scourge of pregnant women in the middle of the 19th century. Germs hadn't been discovered yet, and the idea of washing their hands between doing an autopsy and delivering a baby was anathema to physicians, who strongly resented the implication that they were in any way `dirty,' or that they themselves were the cause of the deaths of between 20-50% of women under their care. Ignaz Semmelweis, an unknown Hungarian obstetrician, concluded that a procedure as simple as hand washing between patients could save nearly all of the women's lives.He was reviled, sank into despair and depression, and died of self-inflicted puerperal bacteria days after being admitted to a madhouse.Neuland's superb book updates a much older book on the same subject, The Cry and the Covenant. It documents beautifully an almost forgotten piece of medical history, as Semmelweis's discoveries were later eclipsed by Pasteur and Lister (who had the simple advantage of living after the discovery of the microscope). Don't miss it.

Almost Getting To the Germ Theory

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Wash your hands to keep the germs away. Even though we aren't really very good at following this rule, and have to be reminded (with questionable results) during flu season, it seems so very obvious. It is hard to imagine the time when people did not know this, when their mommies did not instill it into them so that it was something like an instinct. And yet, even the best medical professionals of the mid-nineteenth century had to be convinced of it, and until they were convinced, they literally killed their patients because they were not washing their hands. _The Doctors' Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignác Semmelweis_ (Norton) by Sherwin B. Nuland tells the story of how doctors learned to wash their hands. It was a surprisingly difficult lesson for them to learn.The problem, for those who could see it was a problem, manifested itself most dramatically in maternity wards. The world had not learned about germs yet, but the doctors did not lack for explanations of what is known as puerperal ("childbearing") fever. Unseen spirits were blamed, as well as miasma, a mysterious condition of stale or unhealthful air. For us, it is obvious what was happening, once we know that doctors doing autopsies were going directly to the bedsides of mothers about to deliver, without the use of rubber gloves or handwashing. But only the young Hungarian obstetrician Ignác Semmelweis could see it initially. Semmelweis could make a clear case for a "cadaver factor" being the cause of the death of so many women. His solution was simple: hands were to be scrubbed with disinfectant between patients. It worked, and Semmelweis had the figures to show it.Unfortunately, Semmelweis turns out to be a deeply flawed hero for this book. He was abrupt, sarcastic, and bullying when he tried to get the doctors to clean up regularly, and he alienated many from his ideas by his abusive personality. He was not only a difficult person to get along with, he inexplicably refused to document his findings in writing and he performed only the most primitive of experiments for verification. He ignored those colleagues who had supported him by fleeing to Hungary when he felt neglected. When he finally did publish, it was in a big, impenetrable book that contained the sort of invective for his foes that he displayed personally. He came astonishingly close to playing a key role in the definition of the germ theory of disease, but simply because of his personality, he had no such influence. He has been pictured before as the upright physician fighting the establishment, and this is somewhat true; but the better picture, given here, is that his own flaws meant that he would not win such a fight. Eventually, he became more obsessed and unreasonable, and his wife had to trick him into confinement at a mental hospital. He seems to have perished there by a beating from the attendants. Nuland's fascinating story shows how an "obvious" medical solution had t

Another fine, short, and concise piece of medical history.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I went through this book in a couple of days. I have always been interested in medical history since medical school, and this was another satisfying excursion into the discovery of so much medical phenomenon in the 1800s. In most ways, it was better for a woman to have her baby at home through help with her neighbors and midwives. America had the luck to be established through pioneers who learned to handle these things on their own, and even in cities, much was done to avoid being placed in hospitals, because it was well-known that if you went into any type of medical institution, you probably were not coming back out. (as proven with Helen Keller's 'Teacher' Annie who was placed with her consumptive brother in such a medical institution...her brother died there).I had heard of Semmelweis before, I think in one of Roy Portland's history. I found his story incredibly sad, because it is often true that we are our own worst enemies, and he was definitely his. Politics in medicine and in education sounds very much the same, unfortunately, and you have to have the ability to bite your tongue sometimes when you want to lash out at people for their stupidity. This was a concept that Semmelweis seemed to be unable to learn, and his running away from Vienna pretty much sealed his fate as per his true theory of puerpeural disease in women. One thing I felt was important that Nuland forgot to take into account, is the standing of women in society, both in Europe and in America. I am not a feminist, but it is goofy to ignore the fact that the care of women was not considered as important medically, as the care of men. This is imperative to remember, that in the politics as played out in Vienna and throughout the world with Semmelweis discovery, not only was obstetrics a relatively new field to male physicians (it had been in the realm of midwives before), but women were important for the bearing of children, but that was about it. More importance was placed on saving the children, then on the women...because a husband/father could get a wet nurse for the child, and remarry again with no stigma attached because he had a child to care for. One thing Semmelweis should be lauded for is placing more importance on the saving of women, and that was different from his colleagues in that they were more interested in their own careers and prestige.I agree with Nuland's critique of the disease that caused Semmelweis mental deterioration as being presenile dementia, rather than tertiary syphillis. Semmelweis was not a man to have gotten syphillis. He was too fastidious, and too busy trying to save lives.Karen Sadler,Science education,University of Pittsburgh

The Cry and the Covenant redux

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Childbed fever (puerperal sepsis) was the scourge of pregnant women in the middle of the 19th century. Germs hadn't been discovered yet, and the idea of washing their hands between doing an autopsy and delivering a baby was anathema to physicians, who strongly resented the implication that they were in any way `dirty,' or that they themselves were the cause of the deaths of between 20-50% of women under their care. Ignaz Semmelweis, an unknown Hungarian obstetrician, concluded that a procedure as simple as hand washing between patients could save nearly all of the women's lives.He was reviled, sank into despair and depression, and died of self-inflicted puerperal bacteria days after being admitted to a madhouse.Neuland's superb book updates a much older book on the same subject, The Cry and the Covenant. It documents beautifully an almost forgotten piece of medical history, as Semmelweis's discoveries were later eclipsed by Pasteur and Lister (who had the simple advantage of living after the discovery of the microscope and the acceptance of the Germ Theory). Don't miss it.

Medicine and politics make strange bedfellows.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Many years ago, I read a story about Ignac Semmelweis that made him out to be a demigod. According to the legend, Semmelweis was a martyr to the cause of saving women from unnecessary deaths due to puerperal or childbed fever. In the early and mid-nineteenth century, childbed fever was ubiquitous and very often fatal in Europe and America.In his fascinating new book, "The Doctors' Plague," Sherwin P. Nuland traces the history of this tragic disease and he sheds some light on how and why the medical profession was helpless to prevent it for so many years. Nuland goes back to the great physician Hippocrates, who, over two thousand years ago, described childbed fever with great accuracy. For all of his powers of observation, Hippocrates knew nothing about the causes of the disease or how to prevent it. For many years, physicians promulgated wild theories, blaming the new mother's milk, bad air, suppression of discharges, and other equally irrelevant factors for the large number of infections that killed new mothers in hospitals. The figures tell the tragic story. At the London General Lying-In Hospital, between 1833 and 1842, 587 women per thousand died of childbed fever. The mortality statistics were similar in hospitals throughout Europe and the United States.Ignac Semmelweis was born in Hungary. As a practicing doctor of obstetrics, he was appalled by the large number of women dying in childbirth. Because he was a keenly observant doctor who kept careful records and because he had a sharp, logical mind, Semmelweis eventually concluded that childbed fever was somehow passed to women from their doctors, nurses, and dirty bed linens. Semmelweis came to believe that simple handwashing with an antiseptic agent and providing new mothers with clean linens would sharply decrease the mortality rate from puerperal fever.Semmelweis was correct in his theory, but he was hated for it. Nuland carefully traces the political climate that made Semmelweis a pariah among his fellow physicians. In addition, the author blames Semmelweis for some huge lapses. By refusing to publish extensive articles describing his clinical findings, by failing to carry out controlled experiments proving his theory, and by alienating those who could have helped him, Semmelweis was reviled instead of respected, and many more women died as a result.Semmelweis did not want to play the political game. If he had done so, he might have become a member of the establishment instead of remaining an outsider. Perhaps then, doctors and nurses would have observed the rules of hygiene before attending to women in childbirth, instead of flouting hygienic practices out of spite and ignorance. Nuland's conclusions are still relevant today. Even in the twenty-first century, politics and good health care are still on a collision course.