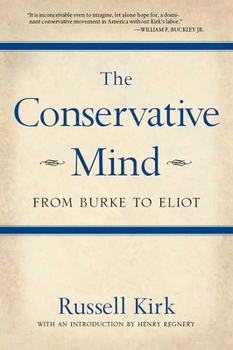

The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"It is inconceivable even to imagine, let alone hope for, a dominant conservative movement in America without Kirk's labor." -- WILLIAM F BUCKLEY "A profound critique of contemporary mass society, and a vivid and poetic image - not a program, an image - of how that society might better itself. [ The Conservative Mind ] is, in important respects, the twentieth century's own version of the Reflections on the Revolution in France... [Kirk] was an artist,...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0895261715

ISBN13:9780895261717

Release Date:September 2001

Publisher:Gateway Editions

Length:534 Pages

Weight:1.78 lbs.

Dimensions:1.5" x 6.0" x 8.9"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Please don't review it if you don't understand it.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Probably most people reading this already know of this book's reputation and influence, so I'll skip over both the chapter-by-chapter analysis and the praise (I'd end up in what Kirk would call "overweening" praise, anyway). But I do want to respond to a typical liberal caricature offered by a previous reviewer. The caricature to which I refer is the idea that a conservative is anyone opposed to change. In fact, the reviewer even argued that the Soviet Union could have been seen as a "conservative" system (an argument endlessly repeated in contemporary media). Perhaps the reviewer missed or didn't understand Kirk's repeated references to conservatism as the "negation of ideology." An ideologist is anyone who tries to rubber-stamp a system of premade ideas onto a society or culture. Think of the "New Soviet Man" in the Soviet Union. Think of the "Cultural Revolution" in China. For that matter, although it wasn't imposed militarily, think of the "Great Society" in America (it worked out about as well as the first two). The "negation of ideology," then, is the conservative idea that one takes societies as one finds them, and then tries to work out change organically from within those societies, rather than imposing it on them from the top. (Think of the current liberal infatuation with attempting to rule America through the Supreme Court for a good example of the "imposing from the top" model.) Sometimes this change can be quite radical, radical in the sense of "getting to the roots" of something, as in the American Revolution (which Kirk discusses extensively). The colonists believed that the liberty they already knew was being circumscribed, and fought to extend it. The reviewer also slanders Kirk in implying he would be in favor of accepting slavery. No, our own Constitution details life and liberty for all, and the organic application of it (as we see in our subsequent history) extends that life and liberty to all. Even the writers of the Constitution, some of whom owned slaves themselves, knew that the Constitution's principles would lead to freedom for all. Lincoln (a Republican, let's never forget) certainly knew it. If you really want to know about the intellectual history of conservatism, this book is where to start. Don't be put off by reviewers whose lack of sympathy for the subject leads them as well to a lack of understanding of the subject.

A Founding Document of Modern Conservatism

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Russell Kirk burst onto the scene in 1953 with the publication of THE CONSERVATIVE MIND, which helped set the course of conservative thought for years. (Murray Rothbard wrote somewhere that prior to this work, conservatives were generally called "the right.") This work went through several editions, and the final (seventh) edition came out in 1986.The focus of this book is Anglo-American conservatism, however Tocqueville does get some attention. Kirk starts with his hero, Edmund Burke (widely seen as the father of modern conservatism) and develops the principle conservative themes down to roughly present times. I found Kirk's discussion of American history quite interesting. He sees Jefferson as a conservative thinker and views Hamilton as a liberal.Kirk introduces you to a number of important authors who aren't generally mentioned by conservatives today. One such writer is the W.H. Mallock who wrote a number of important works attacking socialism and liberalism. Kirk's discussion of Mallock is important in that Mallock emphasized the importance of inequality. As Mallock noted, society advances when those of superior ability are permitted to utilize their talents as much as possible. The less able are in fact the principle beneficiaries of such a system. (This is what Ayn Rand called the "pyramid of ability" principle years later. Hence George Reismann, in CAPITALISM, appears incorrect in claiming that it was Rand who first identified the principle.)Russell Kirk was a member of the Old Right (other leading representatives being Robert Nisbet, Richard Weaver, and Donald Davidson). It's not quite accurate to label him a "paleoconservative" because paleoconservatism has a populist bent not present in the Old Right.

Moral Absolutism and Natural Aristocracy

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

You don't have to be a Conservative to like this book. I found it very useful in understanding the basic worldview from which a Conservative might operate; and from that, one can make good assumptions as to how Conservatives view Liberals. Kirk's thinking is profound, his reading extensive, and his arguments well-written. The major points I took away from this discussion are:1) The Conservative assumes that the design of the world is not by accident, but by transcendental purpose. Metaphysical, permanent standards of Right and Wrong exist: moral standards are not relative. Similarly, the structure of society is not arbitrary. We should not attempt to alter society using science or social engineering, because we are strictly human, and our understanding is limited. Change, when it happens, should be modulated in such a way as to limit its effects on society. 2) A "natural aristocracy" exists in any society. It consists of the best and brightest individuals, and perhaps those born with reserves of wealth. No legislation or voter majority can eliminate it. John Adams defines a member of the natural aristocracy (in a Democracy) as anyone who has the power to influence at least one vote other than his own.3) Individuals are born with certain Natural Rights, consisting primarily of property rights. Government should always act to protect property rights, especially in a Democracy, where the poorest elements of society may employ their voting power to redistribute the possessions of the wealthy few. A Democracy that gives unmitigated power to the people quickly deteriorates into the worst kind of tyranny.4) Instincts and prejudices frequently have meaning: the individual may be foolsh, but the species is wise. The thinking of a few bright persons should not take precedence over tradition.Most of this comes out of Edmund Burke. The Natural Aristocracy theory is primarily from John Adams. The dozens of other conservative thinkers that Kirk discusses tend to modify or enhance the thinking of Burke and Adams. De Tocqueville, for example, sounds the alarm over the potential "Tyranny of Democracy", but that seems to follow from Burke's thinking on natural rights.I had a few exceptions with some minor points. Kirk argues, for one, that the American Revolution was somehow a "conservative revolution"; but I think you could make a more convincing case that it was in fact an Enlightenment-Liberal revolution. Also, he has a tendency to lump all of the different Liberals and Leftists together into a single agglomeration of "Benthamites" (after the British utilitarian/socialist philosopher Jeremy Bentham).On the whole, however, I can recommend this one to any reader interested in understanding how people think politically.

A Conservative Pantheon

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

The book is a sort of intellectual history, each chapter summarizing the thought of one to three conservative thinkers, more or less chronologically beginning with Edmund Burke and running through poets of the mid twentieth century (T.S. Eliot and Robert Frost, among others). The thinkers discussed include intellectuals, clergymen, politicians and poets, all thinking, working and writing in the Anglo-American sphere (most are in fact British or American, but the exceptions -- Tocqueville and Santayana -- wrote in America or for American audiences). A good working knowledge of British and American history from the French Revolution through World War II is therefore a helpful prerequisite to understanding many of these thinkers.The summaries are interesting and informative as description. Many of them (the chapters on Burke and John Adams, for instance, or the section on John Henry Newman) make great introductions to figures whose work can't be read in comprehensive political treatises and many provide intriguing introductions to writers you have probably never heard of (Sir James Fitzjames Stephen) or to the thought of people whom you don't know as political thinkers (say, John Randolph or Arthur Balfour).Among the wealth of description, a little prescription creeps in. Kirk's heroes don't "argue" -- they "know," they "perceive," they "realize," they "understand." Kirk is highly sympathetic with the ideas he summarizes, and it is no coincidence that his final chapter, on twentieth century poets, is called "Conservatives' Promise" and contains some of the most hopeful writing in the book. "If men of affairs can rise to the summons of the poets," he writes, "the norms of culture and politics may endure despite the follies of the time." He ends upbeat, with a call to action of sorts.Not to be missed is Kirk's first chapter, "The Idea of Conservatism," in which he spells out the fundamental tenets which unite the belief of the writers whose work he describes, as well as their photographic negative, the tenets of radicalism. The book dovetails perfectly with George Nash's _The Conservative Intellectual Movement in American after 1945_, which, of course, begins with Kirk himself and which carries on a similar discussion (though Nash omits from his narrative the British half and focuses on intellectual figures, to the exclusion of practical politicians like, say, Goldwater).

One of the 25 most important conservative books

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Professor Kirk was an intellectual disciple of Edmund Burke and an indefatigable identifier and defender of the permanent things in our culture. He left a great body of published works. Starting with Burke, The Conservative Mind surveys the major conservative thinkers of Western civilization. Published in 1953 and updated in subsequent editions, it re-established in America the intellectual respectability of conservative principles, setting the stage for the growth of the modern conservative movement.