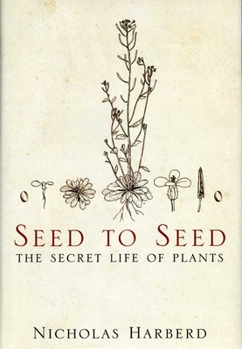

Seed to Seed: The Secret Life of Plants

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A brilliant evocation of the beauty of the natural world and an exhilarating explanation of its secret genetic workings This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1582344132

ISBN13:9781582344133

Release Date:May 2006

Publisher:Bloomsbury USA

Length:320 Pages

Weight:1.20 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 5.7" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

Best Gift Ever!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

My best friend gave me this for my birthday and it truly is one of the best gifts I've ever gotten. I've always loved biology because of its almost mystical qualities. I struggle with the complex jargon and dry language, however. This book is so satisfying for someone who loves science, but doesn't necessarily understand it in a linear way. Harberd explains the science behind plant biology in attainable language and captures all of the beauty and awe that a living thing possesses. What a satisfying, soul-nurturing book!

"It's about seeing"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Completing a research project and polishing off a journal paper left Nicholas Harberd at loose ends. While casting about for a new project, he struck out on a new course. It is good for us that he did. His quest led him to reflect on Nature's mysterious ways in terms that turned him away from his laboratory work to seek fresh insights. Many years of study of the thale-cress, a humble-looking but informative little plant, had provided much detailed information. Harberd, finding a thale-cress atop a grave in a church cemetery, began considering the plant in a fresh view. He developed a broader vision by studying it in Nature instead of his laboratory. As the notes progress, Harberd describes the processes involved in the plant's growth and development. He explains how the leaves bud, then expand, each new leaf set 137 degrees away from its neighbour. The angle is a mystery, but many plants make rosettes of leaves, each with their own separation formula. The core of plant is the meristem, and there are two of these in each plant - one for roots and one for the shoot. There are genetic triggers launching the growth process. Harberd explains how these work and, as far as is known, how they interact. The plant, all plants apparently, start with a set of proteins, the DELLAs, that actually inhibit the growth process. He develops the scene with other genes and their proteins that "restrict restraint" allowing the plant to flourish - if the conditions are right. This book is a reflection of his thoughts, dreams, research problems and other facets of his life and work. Harberd describes the conditions of each day of his note-taking, the weather, the other plants, the soil conditions. The notes are expressive of his reaction to the environment around him, the meanderings of his thoughts as they jump from the pressure of his work to the progress of the little thale-cress. There are setbacks, of course. A slug finds the cress. So does a rabbit, which nearly terminates his study. His reactions in each case are mixed - should he relocate the slug elsewhere? What to do about the rabbit? What happens if caretakers clean up the grave site? Underlying it all are the questions about the next project and what kind of contributions might his group now undertake? What new views of Nature and plant life might result from their work? Non-scientists don't understand researchers or what they do, claiming scientists lack feeling, notes Harberd. Yet, "wonder is what drives us" says this scientist. The feeling of wonder at how things work is the basis of all research. Nature isn't driven by divine mandate, yet Harberd insists that all research results in a sense of awe. As the notes progress over the days and months, the words "wonder", "exciting" and even "breathtaking" appear with increasing frequency. He rediscovers that himself during an Autumn review of his jottings. It's impossible not to be caught up in his enthusiasm as he depicts th

It Was A Very Good Year

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

You know about writer's block, the frightening state of an author who just cannot come up with another idea about which to write. Nicholas Harberd had researcher's block. He had done plenty of work as a laboratory scientist, working out the biochemical mechanisms of some very basic capabilities of growth in plants. Having gotten some answers, there turned out to be more and deeper questions (the familiar pattern that will keep science going forever), but he was not inspired into a next project. What to do? Part of the charm of his book, _Seed to Seed: The Secret Life of Plants_ (Bloomsbury) is that he lets us know how he as a working scientist came to solve that problem. He lets us in on some biological secrets, as he opens up some of the mechanisms that are at the core of what roots and shoots do. Best of all, he gives himself, and imparts to us, a higher appreciation for the natural world, invoking a mystic unity inspired by science, and an appreciation for all the paradoxes that this entails. The specific subject of Harberd's research and his book is _Arabidopsis thaliana_, the thale-cress, a humble weed which has gained stardom as the first plant to have its DNA entirely sequenced. To dismantle the block that has left him uninspired to start up any new project, Harberd started a journal for 2004 to record the history of one thale-cress plant; this book is his journal. His selected plant isn't one of the thousands of plants in his lab, but one in the wild, for which he (and the reader) come to have interest and affection. In watching the plant, he describes for himself and for us the intricate dance between DNA, RNA, and the proteins for which they code. By experimentation, and there is a good deal described in these pages, the exquisitely fine-tuned molecular symphony takes place; even in the humble root of this humble plant there are regulators, and regulators to regulate the regulators, and so on in dizzying iterations. It is fair to ask what use all this detailed knowledge is. Even his daughter, when being told about proteins that restrain the growth of plants, wants Harberd to use them on a neighbor's sycamore that increasingly is shading their garden. The real goal, Harberd says, is not utility (although it is certainly possible that plants are going to be improved the better we know the details of their molecular workings). And for him, the real goal is also not simply a better understanding of how the molecules do their jobs. "I'm more motivated by the sense that understanding brings me closer to Nature. That there's a link between understanding and reverence." It is a pleasure to read Harberd's musings on how nature may be perceived as a unity in different ways, how his plant is so connected with the air and soil around it that distinctions between those entities seem artificial, or how, if one considers the sun as the nucleus of a globe defined by the spread of its light, then the plants which respond to the ligh