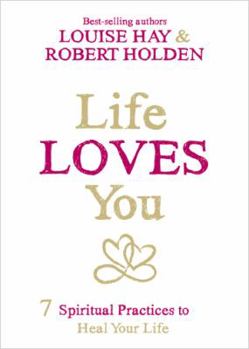

Life Loves You: 7 Spiritual Practices to Heal Your Life

Select Format

Select Condition

More by Anne Mustoe

Book Overview

Life loves you and you have the power within you to create a life you love. Life loves you is one of Louise Hay's best-loved affirmations. It is the heart thought that represents her life and her work. Together, Louise and Robert Holden look at what life loves you really means - that life doesn't just happen to you; it happens for you. In a series of intimate and candid conversations, they dig deep into the power of love, the benevolent nature of reality, the friendly universe, and the heart of who we really are. Life Loves You is filled with inspiring stories and helpful meditations, prayers, and exercises. Louise and Robert present a practical philosophy based on seven spiritual practices. Key themes cover: - The Mirror Principle - practicing the how of self-love

- Affirming your Life - healing the ego's basic fear

- Following Your Joy - trusting your inner guidance

- Forgiving the Past - reclaiming your original innocence

- Be Grateful Now - cultivating basic trust

- Learn to Receive - being undefended and open

- Healing the Future - choosing love over fear

- Affirming your Life - healing the ego's basic fear

- Following Your Joy - trusting your inner guidance

- Forgiving the Past - reclaiming your original innocence

- Be Grateful Now - cultivating basic trust

- Learn to Receive - being undefended and open

- Healing the Future - choosing love over fear

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1401946143

ISBN13:9781401946142

Release Date:May 2015

Publisher:Hay House

Length:272 Pages

Weight:0.79 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 6.2" x 7.1"

You Might Also Enjoy

Customer Reviews

6 customer ratings | 5 reviews

Rated 5 starsLife loves you

By KayD, Verified Purchase

This book is absolutely inspiring..

0Report