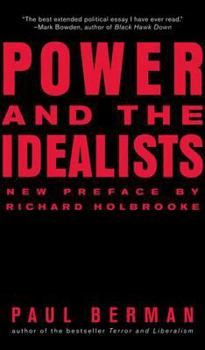

Power and the Idealists: Or, the Passion of Joschka Fischer, and Its Aftermath

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The student uprisings of 1968 erupted not only in America but also across Europe, expressing a distinct generational attitude about politics, the corrupt nature of democratic capitalism, and the evil of military interventions. Yet, thirty-five years later, many in that radical generation had come into conventional positions of power: among them Bill Clinton (who reportedly stayed up all night reading this book) and Joschka Fischer, foreign minister...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0393330214

ISBN13:9780393330212

Release Date:April 2007

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:348 Pages

Weight:0.55 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 4.7" x 7.4"

Related Subjects

Americas Biographical Biographies Biographies & History Biography & History Conservatism & Liberalism Europe Historical Study & Educational Resources History Leaders & Notable People Political Political History Political Ideologies Political Science Politics & Government Politics & Social Sciences Social History Social Sciences WorldCustomer Reviews

4 ratings

Who were the generation of '68?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

In Berman's lucid and wonderfully written account, they were people who were animated by the burning question: Would they have been collaborators or resisters in Nazi Germany and Occupied Europe? They were a generation for whom the question of totalitarianism (be it the totalitarianism that "had survived Nazism" in Western society or the totalitarianism that threatened to murder the Vietnamese Boat People) was a real issue; an issue of foreign policy. A Big Issue, rather than a rhetorical gesture to show that our cause is just. It is not an accident that Jimmy Carter (influenced by the 68ers) established the office of the Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights; that Jimmy Carter "sent the Sixth Fleet into action scooping up the [Vietnamese] Boat People" (who were called such because a `68er who founded Doctors without Borders, Bernard Kouchner, rented a Boat for Vietnam to rescue the Vietnamese who were fleeing the Communists. Nor is it an accident that this same Kouchner became, under Mitterand, France's secretary of State for Humanitarian Action. A title that allowed him to send "humanitarian actions under the tricolor of France" into Africa. For this generation then, the question of Yugoslavia, was not a question of real politik, not a sideline question but a question of central importance. And it is not an accident that this generation (of people who were leaders of the world by then) united (finally and too late some might say but united) and chose to intervene in Yugoslavia on humanitarian grounds. Because "everyone had the right to D-Day". But it was also this generation that, by and large, failed to ask the right questions about Iraq. For no matter how one feels about the Iraq war (and Berman points out some of the more lucid arguments for and against military intervention in Iraq) it is hard to deny that the generation of '68 did not make the humanitarian argument for war against Saddam as it had done for war against Milosevic. It was this generation that kept silent while the "bad US government" went to war for the wrong reasons (with disastrous results for this generation and perhaps the world). It is a generation not without its flaws then; a genuinely human generation. And this is the beautifully-written story about who they were and are and what, in the end, it was all about. I strongly recommend this book.

The Maturation of a Generation of Naive Idealists.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Paul Berman is an unusually fair minded observer of the world political scene. That allows him to do justice both to the idealism of the generation that made the 1968 student "revolutions" and its failings. He charts the development of 1968 street fighter Joschka Fischer to becoming the first Green to be a Minister in the German government. Fischer endorsed NATO's intervention in Kosovo against all his earlier principles. Yet he refused to endorse the intervention in Iraq. Dr.Bernard Kouchner,founder of Doctors Without Borders and another of the '68 radicals,did approve the Iraq intervention, although not how it was carried out. Why did they differ? Berman tells us about many of the characters of the generation of '68, with the whole history of those times and subsequent developments converging on the Iraq question. I wish Fischer's warning that Iraq was a terrorist trap for America had received more consideration from the author. For all those who were young in '68 this book is a must-read. And for other generations too it is highly instructive. Warm, witty and with plenty of narrative, it's compulsive reading whether you agree with its implications or not.

Excellent intellectual history; par for course for Berman

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Paul Berman has written two interesting books in recent years. The first was the excellent TERROR AND LIBERALISM which looked at jihadic violence, its underpinnings in Islamic and Western philosophy and history, and the possibility of a humane, hawkish, antitotalitarian, liberal response to it. POWER AND THE IDEALISTS is an equally engrossing read that looks at the generation of 1968 (anti-Vietnam, anti-authority, anti-capitalist, very often anti-American protesters) and their evolution over time, especially in reaction to Entebbe, Kosovo, and 9/11. Suprisingly, many 1968ers evolved quite far. The emphasis here is on Germany, as the central figure under consideration is former German foreign minister and Green leader Joshka Fischer. This is an excellent, journalistic account of many arguments very pressing in today's political environment. All arguments are treated fairly and in more than just a single dimension.

An interesting book about the idealism of the Left

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

This book is about idealists on the political Left, with a focus on Germany's Joschka Fischer. In the first chapter, Berman shows that the late 1970s brought home to many people just what the New Left had become: it had supported what became genocide in Cambodia and (roughly speaking) National Socialist policies by Arabs in the Levant. These were exactly the policies the Left had opposed so strongly in the 1930s and 1940s. Of course, in the case of Zionism, the Left had switched sides in the past, supporting it in the early part of the twentieth century, opposing it in the 1920s and 1930s, supporting it in the 1940s, and opposing it once again in the 1950s and 1960s. But that's not the point. The Left had generally been against right-wing irredentism, racism, and genocide in the past. And some of it clearly went over to it in the 1970s. In the next chapter, the author discusses some of the ideas of the European Left that "crossed the ocean," such as the Kyoto Protocols and the International Criminal Court. During the Clinton administration, Berman explains that there was an appearance of cooperation between the United States and Europe on these issues. But that fell apart in the present Bush administration. Next, Berman discusses a little about the American Left and the Muslim world. Do those who plead for human rights in the Muslim world get support from American Left? Not all that much. We also discover how much support such rights get in Europe, and in France. How many on the Left in France preferred an American victory over Saddam Hussein to an American defeat? Berman indicates that the ideas of the "generation of 1968," which opposed the Vietnam war and intended to be activists in supporting human rights are not those of this generation. The activists of 1968 wanted to be interventionists. They wanted to oppose oppression. But the ideas of today, on both the Left and Right, are a little different. I think this is a fascinating book, and I recommend it.