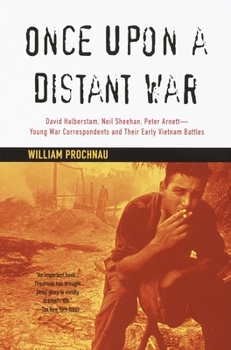

Once Upon a Distant War: David Halberstam, Neil Sheehan, Peter Arnett--Young War Correspondents and Their Early Vietnam Battles

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Once Upon a Distance War tells the stories of such young Vietnam war correspondents as Neil Sheehan, Peter Arnett, and David Halberstam, providing a riveting chronicle of high adventure and brutal... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0679772650

ISBN13:9780679772651

Release Date:August 1996

Publisher:Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Length:576 Pages

Weight:1.22 lbs.

Dimensions:1.5" x 5.5" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A Great Story for All Generations

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

This book is a great read. A meticulously researched account of the lives of young reporters in Vietnam during the early years of American slide into Vietnam. He chronicles what now would be an inconceivable dilemma besetting young men trying to do the job of reporting the truth no one wanted to hear. This is a unique and gripping story populated with characters all well-known to us now. Highly recommend; especially indispensable for anyone planning to visit Vietnam; the places where the events unfold are all still there.

A shadowy period pried open

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Behind Vietnam's shadowy fire-fights of 1961-1963 another kind of combat was taking place, one just as important to the war's outcome. It was a war of words and Prochnau's narrative follows this journalistic battle between a battery of triuth-seeking reporters (Halberstam, NY Times; Sheehan, UPI; Browne, API) and party-line higherups eager to conceal failures in the war's progress. All in all, it's a gripping account.Prochnau avoids comparing press attitudes from earlier wars to Vietnam, yet a comparison is very revealing. In Korea, cover-ups and propaganda pitches went largely unchallenged for two reasons. Most correspondants reporting from there had earlier reported from WWII, a popular patriotic war that had enlisted everyone on the same team. That team spirit carried over to Korea even when the clarities of the fight against Nazi-ism did not. However, by the early 60's, a new generation of correspondants - a young man's job according to Prochnau - had taken over. Steeped neither in team spirit nor in a tradition of placing press objectives below military ones, they were a new breed of journalists unimpressed with the briefings of big-brass officers. Contributing also to the rise of independent reportage was the scale of official deception, which expanded exponentially from Korea to Vietnam. The inflated body counts, Saigon's fishbowl of corruption, and a host of other calamities, all combined to override official deception much more effectively than anything from the early 1950's.Prochnau makes clear that these early reporters - including the trend-setting Homer Bigert - had no basic quarrel with US objectives in Vietnam. Like most observers, they believed intervention was necessary to preserve democracy against the communist menace. Rather, the disagreement was the perennial one over methods and not goals. Thus despite repeated appeals to `join the team', Halberstam and company realized early on that the well-armed Diem regime lacked the political wherewithal to contain the Viet Cong. And though their reporting angered higherups, they believed some kind of iconoclasm was needed to bring about a more effective anti-communist effort. In that spirit, they exposed sham victories when ARVN troops avoided battle but claimed victory, and they wrote about those American advisors dying in battle who weren't even officially there.The fact that government officials abetted these frauds testifies to the level of arrogance and self-deception driving Kennedy's policy at the time, an aspect of press coverage that Prochnau makes clear. The bottom line, however, is that at no time did these rebellious reporters question the fundamental rightness of America's interventionist role. Their faith remained uncritically liberal despite all the sound, fury, and second-guessing from both sides of the information battle. So in some kind of ironical fashion, a larger team spirit triumphed after all.Anyone interested in the early

Journalists as unlikely heros

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This book is a great companion piece to the more popular "A Bright Shining Lie" by Neil Sheehan. Sheehan (along with David Halberstam and others) and his experiences in Vietnam during the advisor period (1962-64) are the subjects of this book. With it you gain perspective of how Sheehan and the others fought an incompotent and deceiptful American and South Vietnamese government establishment that fought efforts to get the truth (that the war was being lost) to the American people. The relationship between the young reporters and Lt. Colonel John Paul Vann (the subject odf Sheehan's book) also features prominently. The accounts are harrowing and sometimes enraging. This book serves as an effective reminder that the press are not always the bad guys.

One good read about reporters and government blunders

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

Everybody might hate the media, but this is as good an account as you'll get of how they work -- or used to. Toss in a first rate history lesson on the government blunders that got us into Vietnam in the first place -- all this told by a superb story teller, William Prochnau -- and Once Upon a Distant War is too good to pass up.

An outstanding study of press-government relations

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 28 years ago

This book has been widely praised as a rich, well-plotted story of the exploits of American war correspondants in the early days of the Vietnam war. But, for students of government and the media, it's much more: it's an illuminating story of how the government uses and seeks to control the press, and how the press seeks to maintain its own autonomy. The theme running throughout the book is how the U.S. government lied to the press and to itself about the progress of the early war. The accounts of wildly inflated body counts, surrealistic assessments of battlefield success, and obvious ignorance of the situation outside Saigon by the American brass is well- known, but worth reviewing. But the book also shatters the post-gulf war myth that journalists had easy access to the story in Vietnam, and were cut out of the story in Iraq when the Pentagon "learned from Vietnam" how to control the press. Clearly, as Prochnau tells us, the government was seeking to control the press in Vietnam, by denying access to critical reporters while giving favored journalists, such as Joe Alsop, the V.I.P. tour of the war, complete with the same distorted statistics and outright falsehoods. The military eventually failed in Vietnam, but not for lack of trying: they failed because the war failed, and too many journalists, from too many mainstream news organizations--AP, UPI, the New York Times--showed that the war was, in David Halberstam's words, a "quagmire." This book would be a fine addition to a college course on the Vietnam war, journalism, or media and politics. I recommend it highly to my students, and to anyone interested in this period of our history.