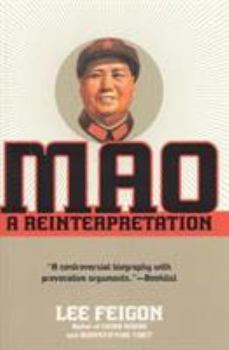

Mao: A Reinterpretation

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Mr. Feigon argues that the movements for which Mao is almost universally condemned today-the Great Leap Forward and especially the Cultural Revolution-were in many ways beneficial for the Chinese people. While not glossing over Mao's mistakes, he contends that the Chinese leader should be largely praised for many of his later efforts. In reevaluating Mao's contributions, this interpretive study reverses the curve of criticism. "Feigon performs a service...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1566635225

ISBN13:9781566635226

Release Date:July 2003

Publisher:Globe Pequot Publishing Group Inc/Bloomsbury

Length:240 Pages

Weight:0.60 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.3" x 8.2"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

Provides a different view of the leader

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Mao: A Reinterpretation is a new political biography of Mao which provides a different view of the leader as a committed revolutionary who contributed to China's history and culture. The real Mao wasn't a genius, nor the evil leader later biographies have portrayed. This reinterpretation examines both his life and the lasting effects of his ideals.

Mao - Stalinist totalitarian, populist rebel, or both?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Lee Feigon's book is not an in-depth analysis of the underlying Chinese and western political philosophies that influenced Mao. (For intro into that, see the outstanding _Maoism and Chinese Culture_ by Zongli Tang and Bing Zuo for the diverse Chinese philosophic influences; Maurice Meisner's and Nick Knight's writings for two opposing takes on the nature of Mao's Marxism; Stuart Schram for a general overview; Anita Andrew and John Rapp for an argument that Mao's ruling style was native autocracy). Feigon chooses to focus on the narrower questions--Was Mao China's Stalin, and his intra-party opponents always more benevolent? Was the Cultural Revolution simply a repeat of Stalin's purges of the late 1930s, or was their some other purpose? In the 1970s, it was trendy to uncritically praise Mao's China as a new kind of society where everyone selflessly struggled for the common good and avoided the usual social blights associated with development. Even those with a more balanced view still understated the repressive side. Through the mid-1980s a more ambivalent view prevailed. Now, the common view is that Mao was a monster like Stalin who pushed more reasonable leaders like Liu Shaoqi out of the way in the process of destroying China. Some even say Mao was much worse than Stalin. Feigon's purpose is to argue against this new popular view. He does so well, but the book lacks balance, which is a significant flaw, and the fact that others like Jung Chang, Jasper Becker, Zhengyuan Fu or Steven Mosher are polemical in the other direction is no justification, nor is the fact that most people have heard that side repeatedly already. For this kind of subject matter, one should write assuming the book may be the only book on the subject for a particular reader. Half of this book is a biography of Mao and a history of the Chinese revolution up to 1949. It seems directed at those with only a moderate degree of knowledge about 20th century China. Yet for the well read, a few conventional wisdoms are debunked. For more detail on this period, see Philip Short's biography. For the post-1949 period, Feigon argues that: a) Mao and the PRC were Stalinist through 1957, after which Mao tried to break with Stalinism b) The break with Stalinism left an important residual impact that indirectly contributed to the struggle for democracy and modernization. Feigon describes the establishment of a Soviet-style state in the early to mid-1950s, and how the 1956 "Hundred Flowers" period was a minor and very limited break with this model. The party pressured Mao to let them silence those daring to criticize the infallible Leninist vanguard. Unsurprisingly, Mao caved and endorsed the "anti-rightist" witch hunts of 1957-58, led with great relish by Deng Xiaoping. The "pragmatists" used the campaign to silence intellectuals and repress workers, even though Mao had insisted that workers be free to strike (later having it written into the constitution, which Den