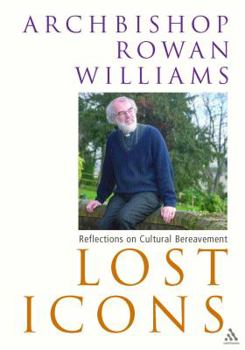

Lost Icons

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In his remarks upon being named Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams spoke of "the Christian creed and Christian vision (that) have in them a life and a richness that can embrace and transfigure... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0826467997

ISBN13:9780826467997

Release Date:January 2003

Publisher:Continuum

Length:200 Pages

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Finding the focus...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Rowan Williams, current Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote the book 'Lost Icons: Reflections on Cultural Bereavement' while he was Archbishop of Wales, primate of a national church in the Anglican Communion outside of England. In his preface, he states that he was working on this book for the greater part of a decade: 'There have been times when I thought this book might more honestly have been presented as a sort of journal of the 1990s.' Of course, during this time, Williams wasn't even Archbishop of Wales; he spent much of the decade of the 1990s as Bishop of Monmouth. This was the era of the Spice Girls, of the death of Prince Diana, of Madonna (the singer, not the Blessed Virgin Mary) and of other media sensations that came to be called 'icons'. An icon used to be used in terms almost exclusively for those images that Eastern Orthodox (among selected others) hold for veneration and prayer. Now it is more likely referring to a computer graphic image; even the media 'icons' have fallen. Williams resists the urge to set out a complex theological and aesthetic theory of iconography, but rather, more accessibly, looks at areas that are more particularly associated with everyday life and ways of thinking. Williams looks at issues of identity, choice and will, society encroachments upon these aspects as well as the recognition of the other, that part of the world and society (including pieces of ourselves) that are outside of us and our own control. Finally, Williams looks at the issue of the soul, hoping to recover a 'lost language of the soul', taking secular language construction to task in theological as well as historical and psychological terms. 'So, this is an essay about the erosions of selfhood in North Atlantic modernity.' This involves issues in politics, economics, and philosophy as well as religion and theology. Williams' grasp of the fundament issues is strong, and his breadth of knowledge to draw these disciplines together in a useful and thoughtful way is impressive. Williams calls for a kind of cultural discourse that goes beyond the modern slogan and sound bite; this may seem radical, but in fact is what the true founders of modern society were calling for against the backdrop of medievalism. Who are we? Do we as individuals each have a self? This is an important consideration - just what does our self consist of? Quoting Joseph Needleman, Williams states that 'Christian doctrine and exhortation are meaningless in our present context so long as we have no idea of what sense of self such teaching is address to.' We are called by Williams to build a new self different from that which media-saturated, postmodern society imposes upon us. Williams finally relates his argument back to the Eastern-style icon and what that means for us today. We have lost focus, lost a luminosity that these icons embody and demonstrate. How can one not love a book in whose index Madonna, John Major, David Mamet, Thomas Merton and the Muppet Worksho

Finding the focus

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Rowan Williams, current Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote the book 'Lost Icons: Reflections on Cultural Bereavement' while he was Archbishop of Wales, primate of a national church in the Anglican Communion outside of England. In his preface, he states that he was working on this book for the greater part of a decade: 'There have been times when I thought this book might more honestly have been presented as a sort of journal of the 1990s.' Of course, during this time, Williams wasn't even Archbishop of Wales; he spent much of the decade of the 1990s as Bishop of Monmouth. This was the era of the Spice Girls, of the death of Prince Diana, of Madonna (the singer, not the Blessed Virgin Mary) and of other media sensations that came to be called 'icons'. An icon used to be used in terms almost exclusively for those images that Eastern Orthodox (among selected others) hold for veneration and prayer. Now it is more likely referring to a computer graphic image; even the media 'icons' have fallen. Williams resists the urge to set out a complex theological and aesthetic theory of iconography, but rather, more accessibly, looks at areas that are more particularly associated with everyday life and ways of thinking. Williams looks at issues of identity, choice and will, society encroachments upon these aspects as well as the recognition of the other, that part of the world and society (including pieces of ourselves) that are outside of us and our own control. Finally, Williams looks at the issue of the soul, hoping to recover a 'lost language of the soul', taking secular language construction to task in theological as well as historical and psychological terms. 'So, this is an essay about the erosions of selfhood in North Atlantic modernity.' This involves issues in politics, economics, and philosophy as well as religion and theology. Williams' grasp of the fundament issues is strong, and his breadth of knowledge to draw these disciplines together in a useful and thoughtful way is impressive. Williams calls for a kind of cultural discourse that goes beyond the modern slogan and sound bite; this may seem radical, but in fact is what the true founders of modern society were calling for against the backdrop of medievalism. Who are we? Do we as individuals each have a self? This is an important consideration - just what does our self consist of? Quoting Joseph Needleman, Williams states that 'Christian doctrine and exhortation are meaningless in our present context so long as we have no idea of what sense of self such teaching is address to.' We are called by Williams to build a new self different from that which media-saturated, postmodern society imposes upon us. Williams finally relates his argument back to the Eastern-style icon and what that means for us today. We have lost focus, lost a luminosity that these icons embody and demonstrate. How can one not love a book in whose index Madonna, John Major, David Mamet, Thomas Merton an

Eloquent and Timely

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

This is the second book by Archbishop Rowan Williams that I have read and, regardless of what one may think of the Anglical Communion, someone such as Rowan Williams must give one some level of hope for its continued (and hopefully unified) existence. Although this work is less theological than a book such as _Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel_ (the other book by him that I have read), it is nonetheless still relevant as it finds its roots in a Christian worldview.What I find both interesting and refreshing about the Archbishop is that he seems far more willing to listen to both sides of an issue than many other religious thinkers. I have heard him referred to as a "post-liberal"; although the usage of the word "post" is all too chic these days, it does seem to designate a type of continuity with a tradition while at the same time a certain level of discomfort with it. Particularly refreshing is his brief discussion about the use of the word "choice" in abortion debates and how the use of the word "choice" presupposes the action/s of an individual are divorced from a social context. Such an understanding of "choice" is, of course, naive; the result of such thinking can all too quickly become an ethics of power, which is contrary to so much of feminist ethics.Williams seems to have a particular interest in language and its place in community, culture, and relationships - not in the purely romantic sense, but in the more general sense of relating one person to an other. He notes several times the place of language in expressing and sharing one's self with others and how certain dispositions - such as a lack of remorse - result in the inability to accurately and fully articulate one's existence in language to another person. His points are well thought out and touch something deep within not only the self, but within the soul as well (for a fuller discussion of the soul and the self, read the last chapter).Disappointingly, the layout of this book is rather frustrating - there are several formatting errors that are completely unnecessary. While the Archbishop's writing makes this book well worth the read, it would have been nice if those that formatted the book had done a higher quality job - a job that matched the Archbishop's work.All in all though, this book is another one by Rowan Williams that is well worth reading - and, perhaps as another reviewer has written, worth reading twice.

A great book with tremendous insights into secular culture

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This book is well written and easly understandable, +Williams presents his arguments clearly and constructs a good framework from the begining. This is not a scholarly work, in the sense that it is written in a more relaxed style, but Williams does a great job in using points made previously in the book to illuminate his current arguments. Although this book is written with a focus upon happenings in Great Britain it is still very helpful for people in the US. I would reccomend reading this book along with some Stanley Hauerwas and other Post-liberal thinkers as there are many points of contact between Williams' critisicms and those made by post-liberals.I highly recommend that everyone read this book; after all, how can I be wrong when I'm so sincere? :-p

A life changing book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

I think this is one of the most invigorating books I have ever read. It is totally uncompromising and incredibly impressive in its breadth and depth of thought. It presents an intellectual and moral structure that goes further than any other I know in explaining personal identity, amongst a host of other things. I very much like its humanity - this is a world view that allows the possibility of remorse that has real meaning, of change and redemption. I don't think it's possible to read this book intelligently without measuring yourself against what it says, but falling short of its high standards does not leave one without hope - the roadmarks are there. This is an honest, kind, and above all brave book. It's also delightful to be given, along the way, a bibliography of other interesting titles. I shall be rereading many times, I suspect, and finding new depths each time.