Last Night I Dreamed of Peace: The Diary of Dang Thuy Tram

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

At the age of twenty-four, Dang Thuy Tram volunteered to serve as a doctor in a National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) battlefield hospital in the Quang Ngai Province. Two years later she was killed by American forces not far from where she worked. Written between 1968 and 1970, her diary speaks poignantly of her devotion to family and friends, the horrors of war, her yearning for her high school sweetheart, and her struggle to prove her loyalty to...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0307347370

ISBN13:9780307347374

Release Date:September 2007

Publisher:Harmony

Length:225 Pages

Weight:1.01 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 5.8" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

Mesmerizing

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

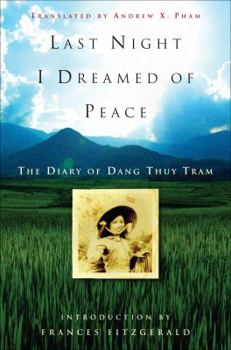

From the moment I saw the cover on this book, I was mesmerized by the rice patties in the foreground, the mountains in the background and the smiling young woman in the cone-shaped hat. The lush green landscape looked eerily familiar. So did the young woman. "Last Night I dreamed of Peace" is the diary of Dang Thuy Tram, a 25-year-old North Vietnamese doctor who goes to South Vietnam during the war to serve in jungle clinics near Duc Pho. Her diary chronicles her life from 1968 to 1970, which was one of the bloodiest periods in the Vietnam War. Thuy writes of her heart-wrenching days in the clinics where she is sometimes forced to operate on patients without anesthesia. To add to her despair, her clinics were often bombed and strafed by American aircraft and sometimes attacked and destroyed by ground forces. If American troops were seen approaching the clinic, Thuy, her staff and patients fled into the jungle or climbed up into the mountains. Sometimes, when there was no time to flee, they crawled into hidden underground tunnels where they anxiously waited as American soldiers searched the jungle above them. I was captivated by Thuy's diary because I also saw the horrors of this war, but from the "other side." I was a U.S. Army supply sergeant for a light infantry company, also stationed in Duc Pho, at the same time as Thuy. It's quite possible that some of her patients were wounded by soldiers from my company. As I read Thuy's diary, I was also struck by her sentiments, which were so similar my own. Enemies in war often share a common likeness, and this becomes evident in Thuy's diary. She longs for the comforts and safety of her home in North Vietnam. She misses her Mom and Dad, her siblings and her friends. Despite these familiar emotions, Thuy's diary is not always easy reading. Her friendships with others on the medical staff, the soldiers and villagers are often referred to as Big Brother or Little Brother, or Big Sister and so forth, ranked according to the intimacy of their friendship and their position in Vietnamese society. Her boyfriend, whom she grew to love as a teenager in Hanoi and still longs for, is simply referred to as Mr. M. In her daily writings, Thuy often struggles with her bourgeois past. She came from a family of educated intellectuals. Thuy's father was a surgeon and her mother a university lecturer. Thuy followed in her father's footsteps, becoming a doctor, and she volunteered to go to the South as soon as she finished medical school. Some thought she was too fragile for such arduous and dangerous work, but Thuy was determined to succeed. This determination constantly emerges in her daily writings, but she continues to questions her bourgeois past and what influence it might have on her relationships with others. Many of Thuy's patients, and the villagers who sheltered her, were probably uneducated peasants. Frances Fitzgerald, who covered the Vietnam War for the New Yorker, wrote an introduction to Thuy's di

humanization of the "enemy"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

"Last night I dreamed that Peace was established," Dang Thuy Tram confided to her diary. "Oh, the dream of Peace and Independence has burned in the hearts of thirty million people for so long. For Peace and Independence, we have sacrificed everything. So many people have volunteered to sacrifice their whole lives for these two words: Independence and Liberty. I, too, have sacrificed my life for that grandiose fulfillment." Thuy never saw the fulfillment of her dream. She was only twenty-seven when on June 22, 1970 American soldiers put a bullet through her forehead. Dang Thuy Tram (b. November 26, 1942) was a surgeon fresh out of medical school who headed a field hospital in the remote, mountain jungles of Vietnam. She operated without anesthesia, rebuilt her clinic every time it was bombed, tended to the peasants whose villages had been burned and bull-dozed, hid in her underground shelter, and suffered the atrocities of war -- kids stepping on land mines, helicopter gunships in the middle of the night, forests stained yellow by toxic defoliants, napalm bombs, amputees, and patients like Khanh, a twenty-year old victim of a phosphorous bomb whose charred body, burned to a crisp, still smoldered with smoke an hour after it was admitted to her clinic. The sparse possessions found with Thuy's body included some medicines, a rice ledger, a Sony radio, and this diary. When the American soldier Fred Whitehurst found the diary during the mop-up, he violated military regulations, kept the diary, and took it home with him in 1972 after three tours of duty in Vietnam. In April 2005 he was able to deliver the diary to Thuy's eighty-one-year old mother and three sisters, who published it in Hanoi on July 18, 2005. In the following eighteen months Thuy's diary sold 430,000 copies -- in a country where two-thirds of the citizens were born after the war ended and where books rarely sell more than 5,000 copies. Much like Clint Eastwood's film Letters from Iwo Jima, Thuy's diary tells the story of Vietnam from the perspective of our "enemy." She's a fervent patriot devoted to Vietnam's revolutionary resistance. She longs for acceptance with the Communist Party which suspects her admitted bourgeois background and attitudes (her father was a surgeon and her mother a university lecturer). She rages with hatred against the American invaders, those "imperialist killers, vicious dogs, bloodthirsty devils, and terrible, cruel people who want to use our blood to water their tree of gold." More importantly, Thuy's diary reveals the longings of a fellow human being who misses her mom and dad and aches with loneliness for her boyfriend. FitzGerald's introduction, numerous footnotes that explain historical details, and two dozen family photographs complement Thuy's deeply human dream of peace.

A tender and wise book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This is a poignant and sad book. The perspective, the daily survival experience of a guerrilla force fighting a technologically sophisticated army, is unique in literature. This perspective obviously speaks to many similar experiences around the world (Chechyna, Iraq, Timor, South Sudan, etc.) --that reaches beyond the political labels that get attached to the various partisans. Yes, the book is somewhat tendentious and overwritten but that is the charm of the honesty of her writing. After all, she was not writing for us, she was writing for herself about her lost love, the sexual tensions in medicine, the fear, the fatigue, the disappointments both political and medical. The reader should accept this voice as one might listen to any young person coming and talking about how confused this crazy destructive madness is. And yet, despite her voice--here is a barely trained doctor--operating without infrastructure, making medical judgments far beyond her experience and training. In this sense, she is older than most of us.