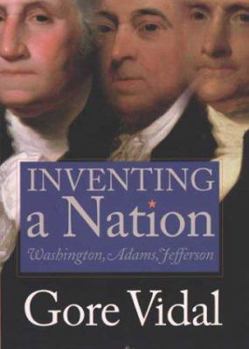

Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson

(Part of the Icons of America Series)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Gore Vidal's uniquely irreverent take on America's founding fathers will enliven all future discussion of the enduring power of their nation-building ideas "Trust Gore Vidal to teach us things we... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0300101716

ISBN13:9780300101713

Release Date:November 2003

Publisher:Yale University Press

Length:208 Pages

Weight:0.90 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.9" x 8.6"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

Vidal's Founding Fathers

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

"How do you explain how a sort of backwoods country [Virginia] like this, with only 3 million people, could have produced the 3 great geniuses of the 18th century - Franklin, Jefferson, and Hamilton?" - this was the question John Kennedy asked Gore Vidal forty years before Vidal wrote "Inventing a Nation." Vidal says "this volume is hardly my definitive answer" to "dear Jack." Vidal produces this sentimental provocation at the end of his "Inventing a Nation" rather than the beginning. Vidal "should" have given this anecdote in an introduction to his book if "should" means we want Vidal to approach the Founding Era as traditional historians do. In fact, Richard Eder is right in his New York Times book review (11/27/03) when he writes, "As history, 'Inventing a Nation' is likely to annoy the historian; it is not a novel, and the polemics come as half-choked asides, almost as if Mr. Vidal had been trying to hold back on them. Frequently, fortunately, he fails. He rambles with one founder, then with another, and then it's back to the first." I might add that (except ending reflections on Kennedy) Vidal has no thesis to work. He attempts no argument that overarches his narrative. A good contrast with Vidal's open-endedness is Gordon Wood's Pulitzer Prize winner "The Radicalism of the American Revolution," where Wood carefully marshals evidence towards a grand historical interpretation. Vidal not only offers no argument, he offers no real narrative, and he offers no citations to his quotations and sources. What is Vidal doing? The LA Times book review said he is writing as "Pure Vidal." That is, he is an essayist and he is using the Vidal-approach to addressing the Founding Era. I will go one step further in my argument, and I will end my review with my thesis like Vidal does his. First, it is right to say that this is "Pure Vidal" because there is much historical knowledge and contemporary interconnectedness in this book. Take for example these witty, controversial, colorful, and contemporary reflections: Vidal can turn-a-phrase: "...Captain Shays, having sold Lafayette's sword to feed his family, took up the terrible swift sword of revolution" (6). "The Electoral College, however, remains to this day solidly in place to ensure that majoritarian governance can never interfere with those rights of property that the founders believed not only inalienable but possibly divine" (67). After Adams genuflects to his Senate a bit too much for Vidal's taste, the latter bites back saying: "The American megalomaniacal style of self-praise was now in place" (69). "...neither empathy nor compassion is an American trait. Witness, the centuries of black slavery taken for granted by much of the country" (77). Vidal comes ever so close to comparing traitors, double-agents, and spies with LOBBYISTS! These latter men, "profit from unpatriotic activities undertaken for domestic and foreign masters" (95). How intriguing is this contrast: Jefferson as a "chi

Americans are better than their government

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Everyone knows George Washington is "the father of his country" who refused a salary as commander-in-chief of the revolutionary armies; the first paragraph of this delightful book points out he collected $100,000 in "expenses." Gore Vidal has an incisive way of cutting through hypocrisy, and in this book he takes aim at the often very bitter and scorched-earth politics that accompanied the founding of the United States of America. His portrayal of just three founders make today's politicians look as wimpy as a babble of Girl Scouts quibbling about their last box of broken peppermint cookies. Pardon me, I don't mean to insult any Girl Scouts; given their ability to sell cookies, they could probably do better than today's "polluticians." He links many pecadilloes of the men who created America to modern times; I think, but I'm not sure, that he wants to contrast the founding idealism of the birth of a new democracy to the banal and petty politics which now infect public life. In reality, this book gives me hope that Americans are far better than their politicians -- in 1787, when they were writing the Constitution, and today when so many politicians are trashing it. Vidal is witty, incisive and a delight to read. One of the warm fuzzy images of Washington shows him wrapped in warm winter clothes as he kneels in prayer in the snow at Valley Forge. Why was Washington praying? Perhaps, as Vidal explains, because he was "dealing with a crooked Congress that was allowing food and supplies to be sold to the British army while embezzling for themselves money appropriated for 'the naked and distressed soldiers,' as Washington referred to his troops." In other words, this isn't your usual history. Washington describes Congress as a place with "venality, corruption, prostitution of office for selfish ends, abuse of trust, perversion of funds from a national to a private use, and speculations upon the necessities of times pervade all interests." It explains why today's so-called conservatives want to go back to the values of the Founding Fathers. He may be too cynical. For example, how competent was Washington? Vidal quotes one British observer who wrote, "Any general in the world other than General Howe would have beaten General Washington; and any general in the world other than George Washington would have beaten General Howe." These are the people who created America. Vidal fails to understand the world in general is run by mediocrity. He should know; he was once a friend of President John Kennedy, a brilliant showman with little substance. It is how the world functions, including the birth of the American system of government from 1775 to 1815. Some politicians are all image and no ideas; great politicians dress noble ideas with inspiring images. Vidal's weakness is that he understands little of England of the era; if he had, he'd understand the American Revolution as a major reform effort of a basically good system rather than t

Superb and thoughtful

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Americans are lucky to have Gore Vidal. Few of our historians (or writers for that matter) have his education, his critical abilities, or his prose. This book is not a history of the early American republic, or postage stamp biographies of the principle players. Instead it's a look at how, pretty much from thin air, a functioning American government was created after the first attempt failed so miserably. From the horse trading at the Constitutional convention to John Marshall's Federalist Supreme Court (which gave us judicial review and saved us from a good deal of Jeffersonian excess), Vidal tells the story of the compromises and conflicts that turned the theoretical government of the Constitutional convention into a living entity.The not so subtle underlying theme of this book is how perverted those institutions have become. Vidal is on record (and has been for more than 30 years) as believing that by 1950, five years after WW II, our generally evolving to a better version of the original republic was being hijacked by political and business forces intent on maintaining the country on a constant war footing. In the famous debate with William F. Buckley in 1968 he made almost precisely the same argument against the Vietnam war that he made against Gulf War II, the gist of which is that since neither Vietnam nor Iraq gathered armies in Mexico it is not the business of a decent republic to make mishcief inside their borders. To spotlight some of those issues, Vidal points out at length how our nascent republic survived largely by avoiding war in Europe. He makes much of Washington's constant preaching of avoiding war (and also much of his incompetence in prosecuting one), notes Hamilton's constant saber rattling, as well as Jefferson's willingness to forgive the heads flying aobut during the excesses of the French Revolution. Another reviewer mentions Founding Brothers, certainly a good book to read, as superior to this one. I think Inventing a Nation is more overtly political, more critical of its subject matter, and funnier. Many people seem to dislike Vidal because he is honest about his subjects. I think he admires Jefferson greatly but can't keep from noting his majestic hypocrisies. He admires John Adams but still spotlights his vanity, occasional shortsightedness, his monarchial tendencies, and his temper. I also think that Vidal is trying to leave crumbs for future generations to figure out just what went wrong in the second half of 20th century. Let's face it, we aren't likely to get 30 more books out of him, and this is one that shows how undemocratic our early republic was and by doing so offers many insights into how undemocratic it is becoming once again.