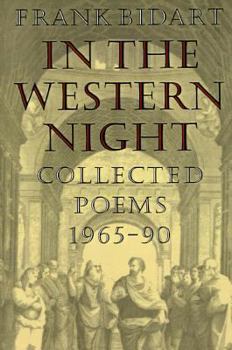

In the Western Night: Collected Poems 1965-90

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In the Western Night brings together in one volume all of the poems to date, including many previously unpublished poems, of one of the most exciting and gifted poets writing today.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0374522715

ISBN13:9780374522711

Release Date:June 1991

Publisher:Farrar, Strauss & Giroux-3pl

Length:256 Pages

Weight:0.82 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 6.1" x 9.0"

Related Subjects

PoetryCustomer Reviews

3 ratings

Modernist experiments meet confessional subjects.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

The best poems in this book launch themselves from Ezra Pound's experimentation with the use of letters, multiple voices, translation and other decidedly non-poetic materials, disjointedly culling these things together to create meaning in how they resonate off one another. Bidart similarly uses letters, grammatical errors, capitalized words, quotes from journals, etc, to infuse into his poems' forms meaning that is crucial to the emotional and narrative understanding coming from the meaning and music of the words themselves. An important achievement. Bidart's success at this is in part what makes readers blow off Pound's Cantos. Bidart's interest is in human relations, and illustrated these through small interactions. While Pound had similar goals in mind, he never stayed long in the personal interaction, jumping so quickly to usury, metamorphosis, and other topics and grand modernist allusiveness. The reader feels to put-out. Bidart stayed with the people, with their hurt. Lowell taught this. Readers can argue the effectiveness, can worry about whether it is wrong for a writer to take interest in his/her own life, but Bidart has in his poems fused two hugely important poetic movements, and has enlarged the understanding of what poetry can be.

Mr. Bidart is our best emotional and fearless poet.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

I was confused at Ms. Greens online review of Bidart's collected poems 'In the Western Night'. I would almost hazard a guess that Ms. green had read a different book altogether. Mr. Bidart is one of the few poets of his generation who is both emotionally articulate and uncompromisingly intelligent. He is able, as few are, to look at the darkness or often horror of this world and not patronize it by inventing hope where there isn't any, or relying on empty though pretty lyric gestures to make things 'all right'. His radical, and neccesary, punctuation was come too over the course of his first two books.The punctuation, as Jonathan Galassi and Donald Hall have pointed out, informs the poem as deeply as line breaks do. It seems to me that Mr. Bidart's poems are some of the few that can hold an honest dialogue with the violence that we are a part of today.He is, in the end, a surprising and wonderful poet.

Bidart's poems solipsistic, unmusical

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 27 years ago

I recall an old Alan Alda movie, "The Mephisto Waltz," in which a famous pianist, about to die, conducts an occult ritual in order to transfer his soul, personality, and musical talent into the body of another man. Similarly, Frank Bidart appropriates and inserts himself into the biographies of other people without seeming to derive any insight into their personalities, their self-understanding. For Bidart -- or, at least, for Bidart's poetry -- the only self that seems really to exist is Bidart's own. The problem is not only that Bidart, as one reviewer has noted, lacks the style or imagination to differentiate between the various characters populating his poems. It's that none of Bidart's characters ARE characters. The client on the psychotherapist's couch in "Confessional," the mad dancer Nijinsky of "The War of Vaslav Nijinsky," the anorectic title character of "Ellen West," even the necrophilic child-murderer of Bidart's early poem "Herbert White" are, in some sense, nobody but Bidart: each character explains his or her own dilemmas in the same way that Bidart explains his own. In "Confessional," Bidart conflates his own story of a mother whom he perceived as a "smotherer" with an anecdote about a strangled cat borrowed from the memoirs of the late 19th-century British travel writer Augustus Hare because, as Bidart reveals to Mark Halliday in a 1983 interview, "I needed it. Everything else in the poem had to be 'true.'" (The interview, originally published in Ploughshares, is included in this volume). Similarly, in his so-called "persona" poems, Bidart invests the lives of his characters with his own self-understanding. There is no attempt to apprehend THEIR self-understandings. However solipsistic his means, Bidart appears in his poems to be making a sincere effort to understand his own suffering. But self-understanding -- or, as it appears several times in his poems, "insight" -- is in the end no match for his apparent need to maintain an aesthetic which turns suffering into an objet d'art, a decoration, while ignoring the more fundamental truths of suffering in a century that has been rife with it. Bidart's prosody is also unconvincing. It is nonmetrical, depending -- as all verse depends -- on line breaks, stanza breaks, and white space to get how to read it across to the reader; and also on idiosyncratic use of punctuation, italics, and capitalization. None of this is objectionable in itself. But unfortunately the language Bidart uses is unmusical, unremarkable, even dull, and dressing it up in capital letters and italics doesn't change it. The principal effect of the all-caps is to make readers feel as though they should shout as they read.