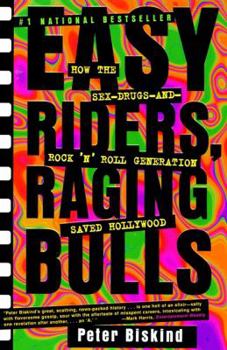

Easy Riders Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And Rock 'n Roll Generation Saved Hollywood

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

When the low-budget biker movie Easy Rider shocked Hollywood with its success in 1969, a new Hollywood era was born. This was an age when talented young filmmakers such as Scorsese, Coppola, and Spielberg, along with a new breed of actors, including De Niro, Pacino, and Nicholson, became the powerful figures who would make such modern classics as The Godfather, Chinatown, Taxi Driver, and Jaws. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls follows...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0684857081

ISBN13:9780684857084

Release Date:April 1999

Publisher:Simon & Schuster

Length:512 Pages

Weight:0.96 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 5.5" x 8.4"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

Vital Movie History

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Apparently, it is good to be a major Hollywood player. What else could explain the incredibly long tenure of the executive corps that reigned over the pictures from just after their founding until the early sixties? For fifty years in some cases, the founders of Hollywood stayed on, and they, with their lieutenants, chose which movies got made, which stars glittered and which fell from the heavens. Yet, even though the old hands stayed on, the audience for movies began to shrink after reaching a high water mark in 1946. Once TV launched, movie attendance began to fall. While ticket sales dropped, the cost of making movies did not, so consequently, the early sixties brought the studios to a crossroads. But, the geriatrics of Tinseltown who continued to make films like "The Sound of Music" and "Oliver" were not the folks to find a new formula. These men, some in the eighties, had no idea what the burgeoning hordes of young people born after the war were looking for. What happened next is the subject of Peter Biskind's ribald book "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls." At the moment when the studios were looking for new filmmaking talent, an unwashed group of rebels waded ashore and began the process of taking the movies in a new direction. These young people, quickly dubbed the New Hollywood, included those that form the aging mainstream of movies today. First through the gate was a drug addled Dennis Hopper, who made "Easy Rider" with the son of Henry Fonda. Jack Nicholson tagged along and rode the chopper of the new wave to a level of fame he was surely not slated for otherwise. This tiny film delivered a staggering return on investment and showed the old order what kind of riches the new kids could deliver if they connected with their own generation. As Peter Fonda stated afterwards, the elderly executives at Columbia Pictures went from shaking their heads in incomprehension to nodding their heads in incomprehension. Many landmark films followed in quick succession, including classics like "Bonnie and Clyde," "The Last Picture Show," and "The Godfather." These decidedly downbeat films did well without any of the old Hollywood formulas. The filmmakers who made them took their inspiration from an older generation of European filmmakers whom they admired. And, there is seems, was the problem that played itself out over the following decade. The European film tradition held that the director was a sort of demigod of the set who exercised total power over all. While such power surely led to the corruption of the Europeans, they lacked the youth and sheer spending power of the Americans to take the crazy behavior to a new level. Once the ball was rolling, the film brats wallowed in each excess, which Biskind relates in tabloid like detail. If it is to be believed, directors like Francis Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Peter Bogdanovich and others scored as many girls and as much drugs as they could stand. Even the older guys like Robert Altman and Rober

A Slice of Life

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Six years and 80-some reviews later, there's no need to repeat many of the points made previously. Two important aspects, however, have been generally overlooked. Personalities aside, the book presents an excellent insight into the shifting power relations between film producers, both independent and studio-based, and film directors, craftsmen traditionally subservient to the producers and money end of production. For a brief period, as Biskind's book shows, these relations were totally muddied or in some cases reversed. Thus, a degree of artistic freedom opened up for a number of aspiring auteurs (Hopper, Altman, Friedkin, Coppola, et.al.), beyond the imagination of such illustrious predecessors as Hawks, Welles, Ford, et. al. In that sense, the book should be of special interest to movie historians, especially those interested in the business side of the industry. Moreover, this shift reflects larger dynamics working their way through the culture as a whole from roughly 1966 to 1975, the insurgent period triggered by the Vietnam war. This alone should be of interest to the broader category of cultural historians. Though the cross-cutting between personalities does get confusing, the interplay among producers like Bert Schneider and directors like Dennis Hopper or between Bob Evans and Francis Ford Coppola provides a real feel of what it was like to be part of the shift and of the New Hollywood. The book also raises the interesting question of how wisdom relates to art. One respected definition of wisdom associates the idea with knowing one's limits and respecting them. Folly occurs when this sense of limits is ignored, resulting in either individual or collective excess and eventual destruction. On the other hand, art often demands that limits be challenged in pursuit of inspiration, personal muse, or some such artistic vision. Drugs, including alcohol, are often looked at as a way of breaking down personal limits. Thus, in simplified form, a basic tension exists between the requirements of wisdom and those of art. Biskind's book offers some pretty clear object lessons on what happens to artistic ambition once all notion of personal limitation is cast aside. Dennis Hopper is merely the clearest, but not the only example. Towne, Bogdanovich, Coppola, and others face a loss of perspective either temporarily or permanently. Egoism takes over, and it becomes no longer possible to separate the demands of vision from those of rampant self-importance. Our culture tends to romanticize the "crazy" artist, but not the "wise" one who is usually much less colorful but understands the value of intelligent restraint. In this respect, "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" presents a cautionary tale to those who would blindly follow the former. Biskind's book may not be a perfect document of the time, but it does remain a highly suggestive one.

A Must For Any Film Lover

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

This book is amazing. Biskind did a great job of writing about what has to be the most innovative and decadent era in American filmmaking. For someone who came to an understanding of great cinema because of people like Scorsese, Ashby, and Coppola, it was fascinating to read about how these guys began and, with the exception of Scorsese, destroyed their own careers. People often think of these guys as icons, yet they fail to realize that these men were just as screwed up as everyone else was. I think this book is not only a great representation of 70's cinema, but it is also a very vivid portrayal of an entire decade of drugs, sex, and excess of both. It also made me think twice of pursuing a career in the film industry. Two questions: Could Margot Kidder and Amy Irving come off any worse than they do in this book? And, is there anyone Warren Beatty did not conquer?

A sad loss of paradise in Hollywood.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

"...But it should have been perfect [but] in the end, we f***ed it all up. It should have been so sweet too, but it turned out to be the last time that street guys like us were ever given something that f***in' valuable again".-Nicky Santoro in the film, "Casino".A common thread in some of Martin Scorsese's films is the "loss of paradise" theme. How cool was the gangster world of "Goodfellas" before Henry Hill screwed it up by dealing with drugs? Or how cool was Saul Rothstein's world in Vegas before he screwed it up by marrying a scam artist? In both of these films the chararacters were given the world and in the end the messed it all up. Have you ever wondered why Mr. Scorsese might have gravitated towards these themes? Well, after reading Peter Biskind's "Easy Riders, Raging Bull", I think you might find the answer.It's a fascinating read about how, for a brief moment, Hollywood went loopy and handed over it's power to the street guys, the directors. Scorsese, Hopper, Beatty, Lucas, Spielberg, Coppola, Friedkin, etc. They became the town's "White Knights" and saved Hollywood from literally going senile. Now, I don't know how many of the book's stories are actually true, but what the hell! It's a fun - lurid read! The only drawback is the depressing ending, which, of course, is how the young innovative directors scewed up and were never given something so valuable, as running Hollywood, again.