Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Hailed by The New York Times as "a passionately felt, deeply poetic book," the moving autobiographical work of Edward Abbey, considered the Thoreau of the American West, and his passion for the... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Mass Market Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0345326490

Release Date:January 1971

Publisher:Ballantine Books

Length:352 Pages

Weight:0.40 lbs.

Dimensions:6.9" x 0.9" x 4.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The Desert Anarchist in His Natural Habitat

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

This is where the cranky hardcore desert conservationism of Edward Abbey truly took wing, and the book is a well-deserved classic in environmentalist circles. In the late 60s, Abbey wrote about his season as a ranger in Utah's then-little developed Arches National Monument (now a heavily "improved" National Park), plus his explorations of the nearby mountains, canyons, and deserts. Of special importance here is the story of Abbey's rafting trip down Glen Canyon, one of the last such journeys before the horrendous dam was built, plus an extremely rare exploration of "The Maze" area near Canyonlands National Park. Abbey surely found his lifelong love of the desert during this time, and the book's philosophy runs toward what would now be called "hard ecology," in which humans are given no place of importance in the natural world – except for those humans who can "really" appreciate it. Of course, Abbey and his cohorts qualify. Abbey's philosophy at this point was rather unfocused and contradictory, as he doesn't mind bragging about carving his name in a tree, or rolling an old tire into the Grand Canyon, while complaining about tourists who don’t have the proper level of respect for nature. His writing is undeniably cranky, irreligious, anarchistic, antisocial, and even anti-human at times, such as the infamous line in which he says he'd rather kill a man than a snake, plus frequent musings on wrecking the monuments of human civilization. However, Abbey's worldview extends far beyond these problematic details, in that he defined the philosophy of communing with nature, which has become incredibly influential to outdoor lovers and serious conservationists. This book is the ultimate resource in learning about how living without the conveniences of civilization can really shape a person's appreciation for the Earth. [~doomsdayer520~]

Uncompromising Environmental Advocacy

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Edward Abbey's Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness, is an autobiographical account of Abbey's stint working as a park ranger at Arches National Monument in Utah. At once this book is philosophical and poetic, yet at the same time, sardonic and polemical. Although the author would probably scowl at such pigeonholing, this book is also a significant environmental statement, as well as being a great piece of literature. In Desert Solitaire, Abbey identifies and adeptly defines a common frustration shared by many writers; the annoyance of not being able to adequately express one's self through the medium of words. He states, "You cannot get the desert into a book any more than a fisherman can haul up the sea with his nets. Not imitation but evocation has been the goal." However, even through his self-styled "evocation", he successfully and intimately enfolds his readers within his unique experience. A reluctant naturalist, Abbey blames the human inability to discern the true meaning of nature, on a tendency to always project our own expectations on the natural world. These are tendencies that exasperate him, and yet when he does achieve a near-true communion, as he describes in his experiences in isolation in Havasu Creek, he finds the encounter more disturbing than ecstatic. He describes losing the power to distinguish between himself and the natural world, creating in him a fear that his sense of self was "ebbing away." In addition, throughout his career as a writer, Abbey refused the label "environmentalist." Nevertheless, his books are useful instruments with which to measure our progress, or lack of progress as the case may be, in our relationship to our natural environment. In this book's chapter entitled, "Industrial Tourism and the National Parks", he lays out his philosophy that "growth for growth's sake is the ideology of the cancer cell." Looking today at the corruption of the wilderness areas that he warned readers about three and four decades ago, it is plain to see how correct he was in his estimation and condemnation of policies pertaining to our National Parks. Whether he admitted it or not, Abbey set a tone of uncompromising environmental advocacy. In looking at Edward Abbey, the reader is also confronted by contradiction. He passionately argues for the importance of untamed wilderness and against the danger of industrial tourism. He declares he would rather kill a human than a snake, and then casually bops a rabbit on the head with a rock, just to see what his own reaction will be. He beguiles us with his description of Arches, and then chides us for wanting to go there. These passionate paradoxes are the tools he uses most effectively to lure us away from our complacency. Most importantly, Abbey's work his work serves as an inspiration to new generations of Western writers and historians, making us realize that wilderness really is a necessary ingredient of civilization.

A voice crying in the wilderness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Edward Abbey was an outspoken wilderness advocate, and his nonfiction writing falls somewhere between Thoreau and Hunter Thompson. "Desert Solitaire" is classic Abbey, written in the latter 1960s, when he was about 30, and it recounts a handful of summers spent ten years earlier in and around Arches National Monument in southeastern Utah. Here he was a park ranger, when the park was still mostly undeveloped. Living in a small trailer, keeping an eye on the campers and tourists, he mostly relishes the quiet, beauty, and indifference of the desert under its hot sun.The book begins with his arrival in April and concludes with his departure at season's end in September. In between are chapters devoted to descriptions of his rambles across the terrain, helping a local cattleman round up cows in the side canyons, trying to capture a one-eyed feral horse, camping on a 13,000-foot local mountain, hiking with a friend into an uncharted wilderness call the Maze, and retrieving the body of a dead tourist. There's also a dark story concerning the unfortunate fate of some uranium prospectors. The longest chapter is a rapturous account of a week spent rafting down the Colorado River, he and a friend among the last to see the canyons about to be inundated by the Glen Canyon Dam and the creation of Lake Powell. Along the way, there are ruminations on the meaning of it all and diatribes against urbanization, intrusive government, the tourist industry, and the destruction of wilderness. The word "solitaire" in the title is an apt choice, as much of the time Abbey is alone, thinking his thoughts and observing this desert world, its plants and wild life, geological formations, and the big sky with its turns of weather. Even when paired up with a companion, he is often off alone, on a walkabout of his own, like as not shedding his clothes. His thoughts, meanwhile, are informed by wide reading in philosophy, history, natural sciences, and literature. As a writer, he's frequently quotable: "Where there is no joy there can be no courage; and without courage all other virtues are useless." "It's a great country: you can say whatever you like so long as it is strictly true -- nobody will ever take you seriously."The vistas he describes so eloquently are not hard to picture in the imagination, but I recommend an accompanying volume of photography, such as Eliot Porter's "The Place No One Knew: Glen Canyon on the Colorado." Unless you're familiar with borage, paintbrush, globemallow, and dozens of other desert species, a picture guidebook to the flora of the region would also be helpful. I thoroughly enjoyed Abbey's book, shared the excitement of his adventures, found his cranky, ornery, sometimes self-indulgent perspective refreshing, and felt saddened by the end-of-season farewell with which it closes. In any list of nonfiction books about the West, it should be near the top.

A genuine and enduring classic about the American Desert

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Edward Abbey's DESERT SOLITAIRE belongs on the shortest of several short lists of 20th century classics, whether we are talking of classic literature of the American West, nature writing, or environmentalism. Why is this such a brilliant book? It isn't the originality of ideas. Other writers-Aldo Leopold, Wallace Stegner, Bernard DeVoto, Mary Austin-had already articulated many of Abbey's central ideas either about nature or about Western policy. Bernard DeVoto was an innovator; Abbey is not. Nor is Abbey's anger and fury at exploiters and defilers unique: DeVoto was just as irate and just as incapable of pulling his punches. Nor is it Abbey's overall vision that makes his book so compelling. Again, both DeVoto and Stegner-and especially DeVoto-evidenced a broader and more systematic understanding of the broader issues confronting the West. None of this is accidental. DeVoto exerted a major influence on Stegner, and Stegner taught Abbey in the Stanford University Creative Writing Program.What makes DESERT SOLITAIRE so marvelous is the almost tactile love and passion Abbey displays for the Desert Southwest. Over and over Abbey summons up specific places, particular mountains, individual landscapes. Although he can write about the desert in general, he more frequently writes about particular spots in Arches National Park and the surrounding environs that help explain his attachment to the West. He is the literary equivalent, in his more somber, reflective moments, of Eliot Porter and Ansel Adams. As a result, what one recalls upon remembering DESERT SOLITAIRE is not words so much as a collection of images.Structurally, the book only resembles a memoir of his time working as a park ranger in the Arches National Park. The book makes it seems as if he worked there only one year, when in fact he worked there two. Furthermore, even what appears as a single year fails to account for all the content of the book. He uses, rather, the fiction of a single season as a framework upon which to hang tales, reflections, and rants. This intermixing of narrative with asides gives the book a richness of texture it might not otherwise possess. The narrative of his time as a ranger gives the book much of it structure, but the rants and sidetracking provides it with much of its content. I hate to write something as trite as this being an absolutely essential book for anyone remotely interested in the subjects it touches upon, but such is the case. Abbey wrote many other nonfiction works and novels. All are interesting, several of them quite good, but DESERT SOLITAIRE is easily his greatest. It truly is a classic.

A Voice Crying in the Wilderness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Edward Abbey didn't like to be known as a nature writer (he was far too proud of his fiction), but after reading this book I would have to say he is among the best. Before I read this book, I had never even considered traveling to the Southwest, this book changed that, and the way I look at nature forever. Abbey has rightfully been called the Thoreau of the American West, this book more than any other shows us why. In Desert Solitaire Abbey is at his best, doing for the Southwest what Thoreau did for Concord and Walden. One of the great strenghts of this book is the way Abbey weaves together such a wide array of subject matter, which illustrates the seemingly endless variety of experience, in what is thought by many to be an inhospitable wasteland. In a collection of breif chapters Abbey touches on everthing from the incredible beauty of forgotton canyons, the Southwest's past inhabitants, a feral horse, the Colorado river, the perils of industrial tourism, and the story of a man who may have came to die at the edge of a cliff. In this book you get a great sampling of everything Abbey has to offer, from his stinging wit and dark humor, rage and sadness concerning the destruction of nature, and finally to hope. Edward Abbey has accomplished on the printed page, what Ansel Adams' photography has done for the Southwest. And yes, both immortalize a time and a place that are being destroyed forever, little by little, day by day, but leaving for us a sad and yet wonderful record of what used to be, and why what is left is worth saving. Desert Solitaire is both a celebration and a lamentation for the disappearing landscapes, and hidden canyons that Abbey chose as his own paradise, and if you read this book it may become yours too. Like Abbey's says get out of your cars and crawl in the sand, and EXPERIENCE what nature has to offer, you might just be surprised at what you find.

Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness Mentions in Our Blog

Celebrating Edward Abbey

Published by Ashly Moore Sheldon • January 31, 2020

In celebration of Edward Abbey's birthday earlier this week, we are featuring a reading list of similar authors who came before and after him. More than just environmentalists, these activists raised clarion calls in defense of nature.

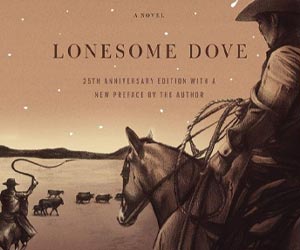

Get Lost in the Wild West

Published by Ashly Moore Sheldon • June 05, 2019

Celebrate Larry McMurtry's 83rd birthday this week with one of these rip-roaring Western adventure tales.