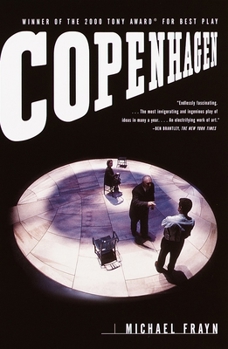

Copenhagen

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

TONY AWARD WINNER - An explosive re-imagining of the mysterious wartime meeting between two Nobel laureates to discuss the atomic bomb. "Endlessly fascinating.... The most invigorating and ingenious play of ideas in many a year.... An electrifying work of art." --Ben Brantley, The New York Times In 1941 the German physicist Werner Heisenberg made a clandestine trip to Copenhagen to see his Danish counterpart and...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0385720793

ISBN13:9780385720793

Release Date:August 2000

Publisher:Vintage

Length:144 Pages

Weight:0.39 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.1" x 7.9"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The play and a fascinating postscript

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

This book contains the text of Michael Frayn's Tony Award-winning play (94 pages), a fascinating 38-page Postscript, and a two-page word sketch of the scientific and historical background to the play.The play itself is brilliant (see my review of the PBS production directed by Howard Davies, starring Stephen Rea, Daniel Craig, and Francesca Annis available on DVD) and is the kind of play that can be fully appreciated simply by reading it. There are no stage directions, no mention of props or stage business. There is simply Frayn's extraordinary dialogue. A photo from the cover suggests how the play might be staged on a round table with the three characters, Danish physicist Niels Bohr, his wife Margrethe, and German physicist Werner Heisenberg, going slowly round and round as in an atom. This symbolism is intrinsic to the ideas of the play with Bohr seen as the stolid proton at the center and the younger Heisenberg the flighty electron that "circles." Margrethe who brings both common sense and objectivity to the interactions between the ever circling physicists, might be thought of as a neutron, or perhaps she is the photon that illuminates (and deflects ever so slightly) what it touches.At the center of the play (and at the center of our understanding of the world through quantum mechanics) is a fundamental uncertainty. While Heisenberg and Bohr demonstrated to the world through the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics that there will always be something we cannot in principle know regardless of how fine our measurements, Frayn's play suggests that there will always be some uncertainty about what went on between the two great architects of QM during Heisenberg's celebrated and fateful visit to the Bohr household in occupied Denmark in 1941. There is uncertainty at the heart of not only our historical tools but at the very heart of human memory (as Frayn explains in the Postscript)."The great challenge facing the storyteller and the historian alike is to get inside people's heads... Even when all the external evidence has been mastered, the only way into the protagonists' heads is through the imagination. This indeed is the substance of the play." (p. 97)The three characters appear as ghosts of their former selves, as it were, and begin immediately an attempt to unravel and understand what happened in 1941. The central question is Why did Heisenberg come to Copenhagen? Was it an attempt to enlist Bohr in a German atomic bomb project? Was it to get information from Bohr about an Allied project or to pick his brain for ideas on how to make fission work? Or was it, as Margrethe avers, to "show himself off"--the little boy grown up, the man who was once part of a defeated country, now triumphant?The play leaves it for us to find an answer, because neither history nor the recorded words of the participants give us anything close to certainty. With the conflicting statements of the characters Frayn implies that the truth may be

An unsolved mystery!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

You might not guess it from the title, but this is the play by Michael Frayn that for several years attracted full house at Broadway and at theaters in London. Background: The atomic bomb was built in Los Alamos during WW II by American scientists, and it signaled in 1945 the start of what we now call the Cold War. But it also ended WW II. Parallel to Los Alamos, German scientists in Leipzig worked on building a nuclear reactor, and the bright young Werner Heisenberg was an undisputed leader of the German fission project. However the science itself originated in Europe. The play has three characters, Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr, and Margrethe Bohr, and the location is the private home of the Bohrs. The book and the play paint a compelling picture of the three. When I went to the play in London, the audience sat in stitches for the whole two hours. I didn't see anyone dozing off, not even during the technical parts of the play. And they most certainly weren't just scientists. Much has been written about the other early atomic scientists, not directly part of the play, e.g., Lise Meitner, Otto Hahn, and Fritz Strassman, to mention just a few. During WW II, in the Fall of 1941, while Denmark was under Nazi occupation, Werner Heisenberg traveled from Leipzig to Copenhagen to see his mentor Niels Bohr. WH had just been 25 years old when he did the work for which he won the Nobel Prize, and in WH's early career, Bohr had become a father figure to the boyish and insecure Werner Heisenberg. The much younger WH was 40 when he visited the Bohrs. Michael Frayn imagines that the three, the Bohrs and Werner Heisenberg meet in after-life to re-live the fateful 1941 encounter, and to resolve WH's motives for his Copenhagen visit; a visit that clearly ended a long and deep friendship. The Bohrs viewed it as a hostile visit, and that never changed, even though Bohr never spoke about what was said in 1941; not then and not later. WH had chosen to stay in Germany after the War broke out in 1939. Why? Did, or did he not, work on the bomb for Hitler? While we may never know the answer, the play offers five possible answers, and we must choose for ourselves. The story really begins before 1941 with the foundation of quantum mechanics in the 1920ties. WH's first paper in Z Physik (1925) is a scientific and a historical mile stone, and it is thought to be the beginning of quantum theory. It is from there we have the ubiquitous notion of 'uncertainty' (of simultaneous quantum observations of position and momentum.) The papers of the three giants Heisenberg, Schrodinger, and Dirac in the 1920ties made precise the theory and the variables: states, observables, probabilities, the uncertainty principle, dual variables, and the equations of motion. This was also when the wave-particle question received a more precise mathematical formulation, and resolution. Perhaps best known are the equation of Schrodinger, giving the dynamics of systems of quantum mechanical particles, a

Science can even explain the darkness in the human soul?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

'Copenhagen' is a history play - it charts those first, exciting decades of the 20th century, when the arcane sphere of theoretical physics reorganised the way perception was perceived, and focuses on two of its totemic figures - the half-Jewish Dane Nils Bohr, originator of quantum theory, and his protege, the German Werner Heisenberg, formulator of the uncertainty principle - and the relation of their work to the literally earth-shattering events around them: the fall-out of the Great War; the rise of Nazism; World War Two and Hitler's occupation of Europe, including Bohr's Denmark; the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. It is a story about what it was like to live in occupied Europe, to work for a fascist regime, to watch your beloved country bombed to smithereens, to be aware of death camps as you cavil over mathematics.'Copenhagan' is a mystery play - the central narrative is a labyrinthine enquiry into what exactly happened on that night in September, 1941, when Heisenberg, now head of the German nuclear programme, paid a mysterious visit to the Bohrs, just before the race laws were about to be enforced. Did he want Bohr's help? His approval? Information on the Allied atomic project? But it is also a perverted mystery play in the old medieval sense, a dark, emblematic representation of biblical events for an age in which religion has died, civilisation teeters on the brink, and scientists become Gods and popes.'Copenhagan' is a philosophical play - it asks how a theoretical physics flagged as restoring humanism (by returning individual perception/point-of-view - relativity - to a conception of the universe) could lead to the atomic bomb and the mass murder of millions. About how the rarefied abstractions of physics had such devastating effects in practice. About who should share more guilt - the ambitious man who collaborated with the Nazis but technically had no blood on his fingers, or the decent humanist who spiritually guided the Los Alamos project.'Copenhagan' is a play about three human beings puzzling over the past and their relations to one another - as you might expect from a work set in Denmark by an English writer, the shade of Hamlet hovers, in the story of a young man agonising over whether or not to act, his fraught relationship with his 'parents', and his acknowledgement of the darkness residing in the human soul. Like 'Hamlet', 'Copenhagan' is a ghost story, in this case crossed with Sartre's 'Huis Clos', with three phantoms condemned to each other's company and uncertainty as to what exactly did happen on that September night in 1941.But mostly, 'Copenhagan' is a play about science, and fearlessly showcases the most abstruse theories and theorems ever conjured. A boffin friend assures me that the play's structure, the way characters move around the stage, the patterning of their actions, the set itself, the shaping of the narrative (an endless circling through time and space around an elusive mystery) are all masterly tr

Art + Physics = Luminescent Fission

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The basic story of Copenhagen--and the playwright's leap of imagination to create the conversation of the 3 principles--deserves any accolades that can be awarded: what if, within one fateful day, the leading scientist for the German nuclear development team had received the insight he needed to arm the Nazis? The ramifications are so huge, so mind-boggling, that it's all the more important that Frayn chose to shrink the scale of his dialogue, and make this play as much about the dynamics of how humans understand each other as how we, as a race, could possibly comprehend the worldwide impact of nuclear arms. This is play about the moral ramifications of decisions made within the supposedly "ethnical no-man's-land" of scientific discovery.Other reviewers have talked about the life history of the scientists, so I'll just sketch out more details about the piece itself. First of all, what an important and revelatory decision Frayn made in including the character of Margrethe, Bohr's wife. In his play, she is the intellectual equal of the physicists, wryly commenting about how many versions of each position paper she spent time typing. Her character makes this play unlike so many science-based dramas before it, because she is a woman and an outsider. Her humor, her humanity and her anger towards Heisenberg's for his involvement with the Nazis...all these issues keep the play grounded in real life, make it palpable to modern audiences not necessarily schooled in the fundamentals of atomic theory. It also insures that the play isn't just the typical strutting, cocksure junk that movies like "Dr Strangelove" aptly mock.I have a serious criticism of the *publication* of this play though: in order to keep it more streamlined (I imagine), they omitted the stage notes for the characters. This is a shame, and makes the reading of it all the more complicated for those who haven't seen the play in person. Having seen it on Broadway, one of the most striking things was the physicality of how this "talky" play was handled. The stage was set in the round, with a small percentage of audience members overlooking the stage as if at a lecture or a medical examination. The stage was completely circular, and the cast members would often take off in spirals, their bodies acting as electrons around the nucleus (most often Margrethe). They would interact, split off in other directions, speed up their rotations. It was a fascinating reenactment of molecular activity, and the dramaturge or editor who approved this edition should be taken to task for this decision. But don't let this dissuade you from picking up "Copenhagen": it's absolute thought-provoking perfection in every other way.

Copehagen:Theoretical Physics Packs with Human Drama

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Who would think that a play about two theoretical physicists, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr would pack such dramatic interest for people with little background in nuclear physics? Yet Michael Frayn's Copenhagen provides both the human drama of the scientists involved in the nuclear weapons race between Nazi Germany and the Allied Forces ,and the ironic parallels between the Principle of Uncertainty in physics developed by these scientists and the unpredictability of outcomes involving human variables in their own lives. My rather "dry " summary of the content of this play, however, does not begin to convey the drama, irony and humour in the play . Three characters, Heisenberg, Bohr and his wife Margrethe met once again after their death to try to understand Heisenberg's "real " reason for his strange visit to Bohr in 1941 in occupied Copenhagen while Heisenberg was heading the German nuclear reactor program. Through the recollection of each from their points of view about the events of the past, the play reveals the personal and professional relationship between the two scientists and others in the elite scientifc community. The dialog is fast moving, sparkles with humor and dazzling description of the mind games of the brilliant and ideosycratic group of scientists. But in these exchanges between the characters, one understands how important and potentially deadly these "games" and the players can be for humanity. With the three perspectives of the same events provided by the three characters, the play reveals mulitple motives and meanings that conclude in the abrupt termination of the meeting between Heisenberg and Bohr in 1941 that might have been the reason that the Nazis failed to develop an atom bomb before the Allied Forces! Or maybe a lost opportunity for deterring the development of nuclear weapons by either side? In two acts, one is absorbed by the levels of relationship between the characters, the irony of academic brilliance and real life failures, the dilemma of pursuit of scientifc 'truth' and responsibility to humanity. Along with all these heady issues, however, ones gains enough knowledge of nuclear physics to see the parallel in the human drama of these scientists in their personal lives. This play is trully a heady trip that makes one want to slow down the racing of ideas in the dialog by going back to catch the multiple meanings one missed in the first reading. It makes one continue to post "what if's" about the development of nuclear weapon and the possible human histories of our lifetime. I saw the play in London before reading the book, but find the book to be a even more satisfying experience. Don't miss it!