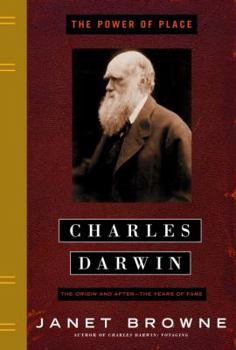

Charles Darwin: The Power of Place

(Book #2 in the Charles Darwin Series)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In 1858, Charles Darwin was forty-nine years old, a gentleman scientist living quietly at Down House in the Kent countryside. He was not yet a focus of debate; his "big book on species" still lay on... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0679429328

ISBN13:9780679429326

Release Date:September 2003

Publisher:Knopf Publishing Group

Length:591 Pages

Weight:2.30 lbs.

Dimensions:1.9" x 6.7" x 9.6"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The Best Biography of Darwin, part 2.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

As several reviewers (including at least one critic of Darwin) have said, this volume is part of the best biography of Darwin yet published. It is hard to criticize this work as Janet Browne has included more detail and hit the nail on the head more times than in any other treatment of Darwin and his ideas. I have read five biographies, several specialized biographies and Darwin's autobiography and can easily say that this by far the best! Browne is simply superb in capturing the spirit of Victorian England and weaving it into a cogent story of the background and inspiration for "The Origin of Species," as well as Darwin's latter work. This volume covers the period from the receipt of Wallace's manuscript on natural selection through Darwin's death. It finally puts paid to the popular notion that Darwin stole his ideas from Wallace, without slighting the originality of the younger man. Darwin was a great thinker, not because he was unusually brilliant, but because he concentrated his thinking on a problem until he came up with a plausible explanation backed up by numerous bits of circumstantial evidence. While many changes have occurred in evolutionary thought because of the genetic and molecular revolutions, Darwin produced the most complete arguments for the common descent of organisms available to science at the time. He thus laid the foundation of our understanding of modern biology. This is true despite opinions to the contrary and, indeed, without evolutionary theory we would have to say goodbye to rigor in not only biology, but geology and astronomy as well!It is my hope that anybody interested in the historical background of evolutionary theory will read both of Browne's books. They are well worth it!

Gentleman, gardener, genius, human . . .

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Charles Darwin's "place" in history is secure. The concept of evolution by natural selection was "the single best idea anyone has ever had," as Daniel C. Dennett so aptly put it. Although the idea seems simple, Browne establishes that the man who conceived it was anything but that. In taking two substantial volumes to depict Darwin's life, Browne reveals the complexity and control hidden beneath his serene outward demeanor. For many years, Darwin's seclusion at Down House left the impression of the retired, retiring scientific thinker. On the contrary, Browne shows "a remarkable tactician" manipulating friends, colleagues and, in the final analysis, society at large. This compelling study is the outstanding work on Darwin. Her focus on his motivations, activities and other aspects of what made him such a towering figure makes this a remarkable work. This magnificent study and its companion "Voyaging" will maintain their value as Darwin's pre-eminent account for many years. The pivotal point, of course, is Darwin's 1859 book, The Origin of Species. Browne recounts the "Wallace letter" which nearly toppled Darwin from the place of priority in developing the idea of natural selection. Darwin's friends and colleagues rallied to sustain him while maintaining fairness to both him and Wallace. The many years of study Darwin had given to the concept resulted in the volume that changed our view of life, but it remains an open question whether he would have published without the "thunderbolt from Ternate." Browne's view isn't narrow, however, as she places Origin within the broader schema of Victorian writing, whether fiction, social commentary, poetry or science. Browne leads us through the years of turmoil following publication of Origin. Strangely, she notes, the chief objectors were fellow scientists, not the religious establishment. Even the British Association debate, often considered the pivot point for making the public aware of the book's meaning, brought out a churchman who had been prompted by one of Darwin's scientific peers. Although Darwin remained at Down throughout the ensuing years, he maintained constant control of those who spoke for him. He reached Continental readers quickly, although troubled by freely editing translators.This account portrays Darwin's "place" by almost every definition of the term. Browne shows Darwin's status among his colleagues, depicts him as a teacher, a father, a member of his community, both locally and in the grander Victorian Era setting. Darwin was a man of his class, most of which endorsed thinking and speculation. Most importantly, she shows his stature as a human, at times fearful, courageous, withdrawing, helpful to his friends and scornful of his enemies. He counseled his children, or used them for help, as the moment demanded. He sought to protect his wife, but Browne makes clear Emma was under few illusions of the meaning of natural selection. Darwin was no hypocrite, but was lo

A Wonderful Life

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Well, this is volume II of a magnificent two-volume biography. In its patient, sympathetic and intelligent rendering it exemplifies those qualities in Darwin himself. Moreover, this is truly the second volume. One could read this without having read "Voyaging" and make sense of it, but Darwin and his world would be less fleshed-out, he and his friends would not be old friends of yours, and the story, which is nothing less than a whole life well-lived (but not, be it noted, perfectly-lived), the less thereby. And what is more, the Darwin-Wedgewood genealogy is not reproduced here - you need volume I for that.Darwin, for someone of such stature socially and scientifically, was a rooted, private man. He rarely left his spacious, gated home at Down except to visit one of his few good friends or relatives. His public appearances were nearly as noted as the Pope's. In spite of this seeming exclusiveness, he maintained an immense and warm correspondence all over the world. Alfred Russell Wallace, for example, was one of his good friends, but almost entirely by means of letters. Moreover, he received a constant stream of visitors at Down, many of whom were hardly known to him, and some of whom barely spoke English.However, these visits were rarely extended beyond a courteous lunch. Darwin would often plead weakness or illness (or let one of the womenfolk do it for him) in order to get away to his study and his studies after being dutifully social. Of course, if it was Huxley, or Lyell, or Hooker visiting, then Darwin had considerably more strength for conversation. These old friends formed the core of his scientific network, and, along with Asa Gray in America, were his representatives in the larger scientific world.The story of Charles Darwin is the story of a homebody: he did most of his experiments with jury-rigged apparatus in his house, garden, or greenhouse, using his children as assistants, and begging and borrowing plant and animal material from his friends and correspondents all around the world, without himself going anywhere. It is the story of a man who loved his wife, and needed her, for he was always "poorly", and he was always busy. It is the story of a man who was warm and affectionate, and constantly a-tingle with some absorbing project in natural history. Yet it is the story of a supremely absorbed man, who was as totally selfish in his dedication to his obsessions as any artist, ruthlessly (but charmingly) using the people around him and around the world to further his investigations, and shield him from those social duties that soak up so much of the lives of most of us.Janet Browne gently disapproves of Darwin's selfishness, which was consistent and on at least two occasions (when he refused to go to the funerals of old friends who had helped him tremendously) nearly unforgiveable. Yet she clearly liked the man, as did almost everyone who knew him (including some of his ideological opponents). He preserved himself for his work, it is

a wonderful read

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

>...One morning in 1858 Charles Darwin picked up his mail and discovered a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace. Darwin had spent 20 years working out evidence to support his theory of natural selection, secure in the knowledge that the theory was too radical and the details too arcane for anyone else to have thought out. He could have published all or part of his work at almost any point; his closest scientific friends often urged him to do so. But he kept silent because he dreaded the consequences: Publication would invite public condemnation likely to make Rome's reception of Galileo look friendly. He didn't think that he could bear the notoriety. <p>Then came the paper from Wallace, laying out the theory of natural selection in words that could very nearly have been Darwin's own.<p>Janet Browne could not have chosen a more dramatic incident to begin the second book of her riveting two-volume biography of Darwin. In the entire range of intellectual history, there is not a moment that tops the Darwin-Wallace collision for sheer human drama. With Wallace somewhere in the remote rain forest of southeast Asia - weeks away by the fastest steamers - no one would ever have known if Darwin had "lost" that manuscript. It is unlikely that he even considered such a course.<p>Over the course of these two volumes, we come to understand the man's character intimately. Partly because Browne has waded through endless bundles of family letters that have sat unread since the original recipients tied them with silk ribbons. Partly because Browne, a British professor of the history of biology, understands Darwin's world. But mostly because she is a master of the art of biography.<p>Darwin was bound to publish Wallace's paper. The great question was, would he publish his own? His agonized decision came down to deciding which he dreaded more: facing the public scorn that evolution aroused in Victorian England, or allowing credit for the theory that had been his life's work to go to someone else. At this point the story becomes weirdly modern.<p>Darwin inhabited an old-fashioned world that is very foreign to us. He got the chance to explore not because he was a qualified scientist, but because he was a conversable gentleman from the right sort of family. He never held a paying job. Some English gentlemen did work, but it was more respectable to settle in a big country house and live on inherited money. Charles married his first cousin, and each of them inherited part of grandpapa Wedgewood's china fortune.<p>But the most startlingly unmodern thing about Darwin was, in the words of his son Francis, "the curious fact that he who has altered the face of Biological Science, and is in this respect the chief of the moderns, should have written and worked in so essentially a non-modern spirit and manner."<p>During the course of Darwin's career, scientific instrument makers began to produce equipment that improved, for example, the control of moisture or light available to gro

The Best Biographical Work on Darwin

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This is the second volume of Janet Browne's outstanding biography of Darwin. The first volume, Voyaging, covered Darwin's family, childhood, early adulthood, the voyage of the Beagle, and the formation of his ideas of evolution and natural selection. This book begins with Darwin established firmly as a major figure in British (and international) scientific life and settled happily with his large family at Down House in Sussex. Working on several projects and slowly on what he intends to be a major series of volumes on the 'species question', which he has essentially solved years earlier, Darwin's tranquility is disturbed when he receives a proposed article from the itinerent naturalist and collector, Alfred Russell Wallace. Seeking Darwin's patronage for his ideas, Wallace has also developed independently a theory of evolution and natural selection. This event precipitates Darwin's publication of his ideas and the publication of the first of his many books on evolution. The result is modern biology and Darwin's ascent from esteemed scientist known to a small circle of colleagues to Victorian celebrity. Browne presents Darwin as a man who was in many important respects a deeply conventional Victorian. A benevolent patriarch who governed his family carefully but firmly, he had conventional moral views. His politics were Liberal but not Radical in nature, reflecting his middle class and Dissenting family background. Strongly attached to his home, he shunned publicity and preferred family and a close circle of friends to a more open social life. He had a retiring personality but a strong sense of responsibility and served as local magistrate and as a vestryman for his local parish. Browne emphasizes his strong sense of connection with his home, his rural neighborhood (if that is the correct term), and his country. Beneath this surface of conventionality and parochialism, Darwin was a decidedly unconventional thinker and a man with an unmatched perspective on the natural world. Darwin spent hours every day engaged in correspondence on biologically related subjects. His accumulated correspondence (of which Browne is co-editor)comprises thousands and thousands of letters. He had an international network of correspondents and pursued information on a dizzying array of topics related to biology and natural history. Darwin was undoubtedly the best informed biologist of his time and possibly in human history. Once he developed his basic insights into evolution and natural selection, Darwin pursued his ideas to their logical conclusions. This led him to deeply unconventional ideas, notably the abandonement of any notions that a higher power guided life on earth. Most of his closest collaborators and friends could not follow him along this path. Wallace, for example, could not accept that natural variation and variation seen in domesticated animals was due to the same underlying phenomenon. Wallace could not also accept that human evoluti