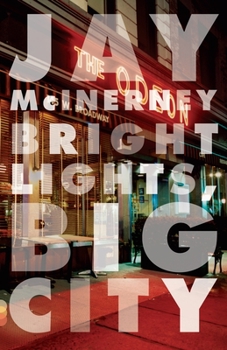

Bright Lights, Big City

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

With the publication of Bright Lights, Big City in 1984, Jay McInerney became a literary sensation, heralded as the voice of a generation. The novel follows a young man, living in Manhattan as if he owned it, through nightclubs, fashion shows, editorial offices, and loft parties as he attempts to outstrip mortality and the recurring approach of dawn. With nothing but goodwill, controlled substances, and wit to sustain him in this anti-quest, he runs until he reaches his reckoning point, where he is forced to acknowledge loss and, possibly, to rediscover his better instincts. This remarkable novel of youth and New York remains one of the most beloved, imitated, and iconic novels in America.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0394726413

ISBN13:9780394726410

Release Date:August 1984

Publisher:Vintage

Length:182 Pages

Weight:0.50 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.2" x 8.0"