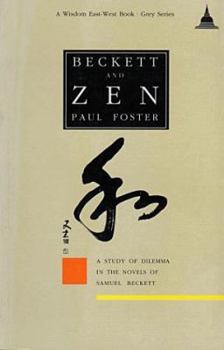

Beckett and Zen: A Study of Dilemma in the Novels of Samuel Beckett

Applies an understanding of Zen Buddhism to the 'absurdity' of Beckett, which is seen as an expression of deepest spiritual anguish.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0861710592

ISBN13:9780861710591

Release Date:January 1989

Publisher:Wisdom Publications (MA)

Length:295 Pages

Weight:0.05 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.4" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

1 rating

Facing the impasse, impaled on the dilemma, seeking a way out

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

This aim nears an elusive target. Foster aligns Beckett's dilemma-- there is no God vs. we must seek God-- with the adjacent attempt by Buddhism to veer away from a "monorail" linear quest that traps his characters to see only before or behind themselves in their existential exiles. Foster argues that their author, like his subjects, lacked the ability to turn off this doomed road, where Beckett's dilemma's solved by leaving it and a/theism and existence as we know it and cannot know it otherwise all behind. Rather, the true adept rejects mental constructs of a panicked ego, for a Zen search for immersion into that beyond anguished thought, careless diversion, or misleading faith: into One Mind, the ultimate Unnam[e]able. In fact, Foster could have called it a "trilemma," for not two but three horns rise. We face a world of senselessness without God, we lament our impotence to change this abandonment, and we endure our lives without solace. Foster, a longtime practitioner of Zen who returned to academia to write the 1980 dissertation that became this 1989 book (published by a Buddhist-themed press), employs Beckett's examinations of the mind in his major prose texts as a spiritual tool for exposing the ontological strengths, and ultimately weaknesses, of what happens when, like Beckett dared, you sit and contemplate your fate. Without bowing to a god, without killing yourself, without either total despair or total comfort. A grim scenario for many of his characters and we his readers, but Foster bravely delves in to formidable narratives to apply his Zen-mind to Beckett's men and women who hesitate to make the "great leap" demanded in Buddhism of those who would gain power over their impotent selves. In "Murphy," hints of Buddhism surface, but I agree with Foster that these are passing and rather inconsequential. As with Scripture, one can read back into Beckett a myriad of critical intentions that the author may not have intended at all. For "Watt," sophistry parodied wearyingly may veer near a Buddhist solution, however unintentional, when it comes to nothingness. "The difference is between the two is that where the one ends in brilliant but brick-wall theory, the other finds a way over the wall in practice. Where the one, like Watt, screams in an impasse of despair, the other initiates a revolution of mind that transcends both self and impasse." (150) The prose trilogy that Foster takes on causes him, no less than any other than the most shallow commentators, problems. As with the previous two novels, with "Molloy" and "Malone Dies" he ends both his chapters on the first two installments at what to me appears very much like a brick wall. Both novels break down, and while Foster excels at extracting fragments to shore up against ruin of the agonized narrators, I sense that he cannot solve the dilemmas that Beckett through his prose confronts without being able to resolve. The honesty of Beckett prevents him from doing so. Foster, to his c