L'Orient Ancien Et Nous

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

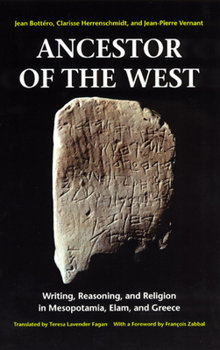

With Ancestor of the West, three distinguished French historians reveal the story of the birth of writing and reason, demonstrating how the logical religious structures of Near Eastern and Mesopotamian cultures served as precursors to those of the West. "Full of matter for anyone interested in language, religion, and politics in the ancient world."--R. T. Ridley, Journal of Religious History "In this accessible introduction to the ancient world, three leading French scholars explore the emergence of rationality and writing in the West, tracing its development and its survival in our own traditions. . . . Jean Bottero focuses on writing and religion in ancient Mesopotamia, Clarisse Herrenschmidt considers a broader history of ancient writing, and Jean-Pierre Vernant examines classical Greek civilization in the context of Near Eastern history."--Translation Review

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0226067165

ISBN13:9780226067162

Release Date:January 2000

Publisher:University of Chicago Press

Length:208 Pages

Weight:0.60 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 6.4" x 9.0"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

Informative and scholarly work

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This book consists of three long essays by different authors, one of whom is Bottero. It's a good book, but it's more technical than Bottero's Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, and if you're thinking of reading this book, I would recommend you probably read the latter work first before tackling this volume in order to get some extra background, unless you're already well versed in the subject. Before reading this book, I also read a brief history of the ancient Sumerians and Akkadians to get at least a basic grounding in the history and something of a historical context, since, as I said, this book is significantly more technical, and perhaps, a little dry as a result, but it's still an impressive piece of scholarship and well worth reading. Bottero's Everyday Life is also written by a team of authors, with Bottero writing several of the chapters. It's quite readable, as well as extremely interesting, and has chapters on Love and Sex in Ancient Mesopotamia, Religion, the Law, Food and Cuisine, Women's Rights, etc. Overall, this work is a valuable contribution to scholarship in the area with much good information and some important theoretical discussions on the nature of thought and culture in ancient Mesopotamia.

Very good

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

This book is actually three essays. Each essay is split into several subject matters and thus becomes a neat secondary source for any student of the subject at hand.The first, by Jean Bottero, is superbly crafted for the general reader who wishes to learn more about, as he says: "History begins at Sumer". The language does not, unlike Clarisse Herrenschmidt's second essay, presuppose a detailed knowledge of the subject at hand. Bottero outlines his premise that Mesopotamian culture is a direct descendant of Semite (Akkadian mainly) acculturation of Sumerian culture. He argues that writing evolved as a mnemotechnical device beginning with ideograms and pictograms. He gives a pellucid explanation of the definition of religion, stating it presupposes a belief in the 'sacred' or 'supernatural'. I.e. a higher order that manifests itself in two ways: Either through religiosity - a reverence or love for the order, or centrifrugally - a fear of the order. What is particularly good about Bottero's writing is he makes statements and then spends some time explaining clearly what the terms of his statement mean. For example, many scholars would state the Mesopotamian religion was not historical and leave it at that. Bottero gives a concise and very understandable definition of the term.The second, by Clarisse Herrenschmidt, far more than Bottero, presupposes knowledge of the subject at hand. Therefore, it is slightly less accessible to the general reader. Given her essay is the longest of the three this is a shame. Nevertheless, Herrenschmidt opens, spending considerable time explaining why proto-Elamic is untranslatable and then tends to run away like any excellent scholar into the intricacies of language and its development from the consonant alphabet to the Greek vowel-using alphabet of eighth century Athens, to the detriment of the general reader who will invariably get lost along the way in the tricky twists and turns of intellectual theorizing. Aside from that, the essay has a long discussion the development of consonants and states that an alphabet is ruled by the rule - one sign = one sound. Not entirely sure I agree with that, as the english alphabet has many variances of sound on its letters. Anyhow, there is an excellent brief history of the technical evolution of writing and its links to social recognition. Herrenschmidt basically states that, in a barbaric society, (which she never really defines) speech = power. From here Herrenschmidt goes on to major discussion on the Mazdean Avesta and from there to Greek. She ends by saying Greek was the language of culture, Aramaic the vernacular, and Hebrew that of the sacred corpus. The concluding section places far too much emphasis on the Greek dropping of the aspirated 'h' in eta c.403 B.C; for example, in the statement: "They thus prohibited the privatization of breath through writing, because speech was for everyone and that included the gods." What exactly does that mean? So, Herrenschmidt's ess