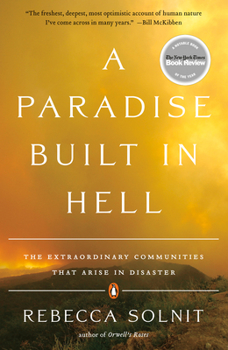

A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A New York Times Notable Book Chosen as a Best Book of the Year by the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, New Yorker, San Francisco Chronicle, Washington Post, and Chicago Tribune "A landmark book that gives impassioned challenge to the social meaning of disasters" --The New York Times Book Review

"Solnit argues that disasters are opportunities...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0143118072

ISBN13:9780143118077

Release Date:August 2010

Publisher:Penguin Books

Length:368 Pages

Weight:0.77 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 6.5" x 8.5"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Good Book... Lots To Think About

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

This book is a good read and gives much food for thought. Not sure it lives up to its title but all and all a good book.

the truth about reaction to disasters

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

This is a very interesting book with an entirely new thesis of how posttrauma crowds respond. It reflects more of my experpience of individuals' and groups' behavior after an unexpected trauma. I wish the author would be on the talk shows to challenge the common belief that people are irresponsible and criminal in their reactions to terrible events. The authorities regularly create more problems than they solve.

Leaner is better.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I won't rehash all significant points that the other two reviews provide, since these are quite adequate for a basic understanding of Solnit's thesis. This book is good. The thesis is quite original, and you are thoroughly convinced by the end of the book that disasters and catastrophes are two different things. She brings different sources to bear in making her point, ranging from newspaper articles to eyewitness accounts to interviews she did herself. I found a lot of the information fascinating, and I am glad I read this book (the publisher seems to have forgotten how end notes work, however). That said, I hesitate to give it 5 stars because of the style. Just as the title of my review states, this book would have greatly benefited from some close editing. Some of the prose is repetitive, and sometimes it strays from the point. For instance, her account of the earthquake in Mexico City bridges at least two chapters, with a large segment in the middle talking about Carnival and Santos. Interesting stuff, but was this needed? Probably not. Sticking to the disasters and the case studies would have made this book 5 stars. I wanted to give the book more credit, but at times it felt disorganized, as if it was a compilation of a series of medium length articles. All things considered, however, I would recommend this book. Pick it up if you are at all interested in disaster studies.

We Are Better Than We Think We Are

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Before I picked up this book, I didn't even know that there was an academic field called "disaster sociology." It turns out it goes back to William James himself, an eyewitness to the 1906 San Francisco earthquake who had the open-mindedness to look at how the people of San Francisco were affected by that disaster without projecting his own prejudices on it. He was astonished; people in disasters don't act anything like how we would expect them to. James' findings have been replicated by studying people in hundreds of historical and modern disasters, and from those studies disaster sociologists have come to some concrete, reliable scientific findings. Solnit believes very, very much that the rest of us need to know what the disaster sociologists know, because our mistaken expectations of what will happen during and immediately after disasters keep making things worse, not better, for the survivors. Before James Lee Witt took over FEMA, and ever since he left, it's been a standing joke that all disasters come in two phases: the disaster itself, and then the even worse disaster when FEMA arrives. This is not a coincidence; Witt knows things about disaster that almost nobody else in America knows, including other first responders, and it showed up in his priorities. Solnit draws most of her examples from four disasters and their aftermaths, each recounted in detail: the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the 1917 explosion of an ammunition ship in Halifax harbor that destroyed the city, the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, and the World Trade Center attack on 9/11 of 2001. Other earthquakes, hurricanes, bombings, and other disasters are cited for comparison and contrast. And here's what she reports, based on extensive research by multiple scientists into the actual first-hand accounts of people who lived through disasters: During a disaster, heroism is not particularly rare. Before a disaster, most people predict that they will panic, will react selfishly, will be cowards. It turns out not to be true. Most people don't run away from a disaster, they run towards it to see if they can help. Most people don't trample others to get away, they stop to pick each other up and help each other along. We keep being surprised by the fact that in an actual disaster, we are nearly all better people than we are in our daily lives. Disasters bring out the best in almost all of us. This is the book's single most important finding. It is extensively documented, and that's important, because most people will find it to be the most surprising. Disaster survivors do not panic. Actual examples of people succumbing to helplessness and going catatonic, or of rushing around destructively in panic, are seldom if ever found. When people self-evacuate, they almost 100% consistently do so calmly, in an orderly fashion, and spontaneously cooperate, even at their own risk, to carry out the wounded and the disabled. Crowds of people have trampled to death the injured and the fallen in

Disaster utopias and elite panics: 4.5 stars

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Sometimes, a book comes along that forces me to stop reading every few pages. Not because it's badly written, clumsily argued or otherwise defective. But simply because it's so provocative, so compelling and so articulate that I had to pause in order to digest a whole raft of new ideas, toss out some old preconceptions and ponder some important questions. Solnit's core argument -- that we can find hints of a humanist-style utopia in the world's worst disasters -- is not only provocative but fascinating, as she amasses a host of evidence to prove her point from the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 up to Hurricane Katrina nearly a century later, disasters that range from the Halifax explosion during World War 1 to the terrorist attacks on 9/11 in both New York and Washington. In the midst of these disasters, as she chronicles repeatedly, people -- ordinary individuals, not institutions -- rose to the occasion. Rather than panicking, they acted, whether that meant battling to save lives or simply to reach out to strangers in random acts of love and compassion. With disaster, paradoxically, can come joy, since in disaster it is possible for those of us not immediately afflicted to rediscover a sense of community and purpose that is otherwise absent from our lives. "The desires and possibilities awakened are so powerful that they shine even from wreckage, carnage and ashes," Solnit writes. Solnit was driven to write this book by her experiences in California's Loma Prieta earthquake; I was compelled to pick it up by my own experiences in the heart of lower Manhattan on September 11, 2001. I witnessed sights that continue to give me nightmares, but experienced (and to some extent participated in) the kind of reforging of a spirit of community of the kind that she describes. I had stranded strangers camped out in my apartment, and, after trekking across the Brooklyn Bridge to my home, benefitted from the help of others (like the woman standing with a roll of paper towels making makeshift nose filters to block out the smoke and stench wafting over us). What this book does, however, goes well beyond simply chronicling the many and very compelling personal stories that form part the evidence supporting Solnit's case. The phenomenon of joyousness and purpose found amidst destruction naturally raises the question in her mind of why it takes a disaster to do this -- and why it is that the preconception is that we will all behave like headless chickens or -- worse -- as violent lunatics in response to a crisis. So she formulates her second theory, one that is more provocative still -- that of 'elite panic'. Those with a vested stake in the status quo, whether they are politicians, corporations or even established charitable organizations, have found that disasters can be dangerous for them. After all, earthquakes in Nicaragua and Mexico exposed and made unacceptable the immense shortcomings of both countries' political regimes (in the former case, the So