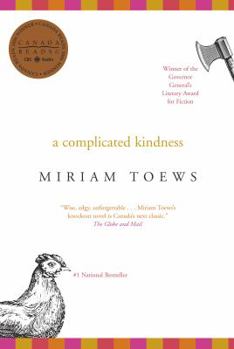

A Complicated Kindness

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

This "darkly funny and provocative" coming-of-age novel balances grief and hope in the voice of a witty teenage girl whose Canadian family is shattered by fundamentalist Christianity (O, The Oprah... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0676976131

ISBN13:9780676976137

Release Date:June 2005

Publisher:Vintage Books Canada

Length:246 Pages

Weight:0.66 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 5.3" x 7.9"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Rebel angels

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Nomi, the first person narrator, is growing up in an isolated Mennonite community in Manitoba. They apparently drive cars and use electricity but are sufficiently distinctive that tourists come to photograph them. (She has great fun mocking the attitudes of the tourists.) There's a lot of interesting background information about Amish and Hutterite sects, which show remarkable parallels to Jewish orthodox and Hasidic groups. Nomi recklessly defies all the rules and leads a life more untrammeled than she probably would have been able to do in her longed-for New York City. Her family ultimately breaks up because the rebellious ways of some of its members result in the community inflicting the punishment of "shunning" which causes them to have to choose between obeying the religious rules and maintaining contact with the shunned. It challenged comparison with two other books I had recently read about girls growing up in religious groups circumscribed by religiously based restrictions. Those were Pearl Abrahams' "Romance Reader" and Kelly Kerney's "Born Again." All three are great books, and all are deliciously funny at some points. I thought Kerney's was the best. That's to some extent because Kerney is such a great prose writer, but also because her plot centers on the issue of the belief itself rather than just the restrictive social conventions it imposes. The central issue for Kerney is whether to believe or not believe. The central issue for Toews and Abrahams is whether to conform or not conform.

Amazingly Real and Funny Book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This was a surprise find and an awesome one at that. Funny and sweet, the "Menno" teenage author is falling, falling, falling out of grace with her strict Mennonite community; stoned half the time, confused the other half, she takes us into the world of a small-town religious town girl yearning for something more.

Funny, sad, comlex and absorbing

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Narrated by a rebellious Mennonite teenager, Nomi Nickel, this funny, sad, wry, perfectly titled novel (but you have to read it all the way through to see why) takes place in a rural town in Southern Manitoba, where the Mennonites settled to preserve themselves from the corrupting world. Nomi's elder sister, Tash, and mother, Trudie, have left home ("Half of our family, the better-looking half, is missing.") and Nomi spends her days wondering why her family has disintegrated, pondering her own escape, and expecting to end up working at the chicken processing plant down the road. The town, East Village, is a tourist destination; a place Americans come to gawk at the "simple life," exemplified in the museum town constructed at the edge of East Village. The real town, however, disappoints the tourists. Cars fill the streets, the inhabitants wear ordinary, if subdued, clothing, and enjoy the advantages of electricity and indoor plumbing. But Nomi is also confused. "There were so many bizarre categories of things we couldn't do and things we could do and none of it has ever made any sense to me at all." They could watch "Batman," but not "Swiss Family Robinson," could play golf, but no pretend games. Life is meant to be a sober, austere preparation for eternal heaven after death. "There's not a lot of interest in the present tense here. And it's only slightly disconcerting that everyone's related. If a Mennonite couple divorces do they still get to be cousins? Oh yeah, hilarious. Tash once said to my mom: Oh, so it's wrong to move any part of one's body in time to music but it's perfectly okay to penetrate members of one's extended family? My mother told her not to be silly." Nomi's mother was a high-spirited woman with a worldly yen, who took her religion seriously. Her inner turmoil remained mostly hidden until Tash began openly and angrily to turn her back on the church. Supporting her, protecting her and sometimes taking her part brought Trudie into open conflict with the church, personified by her brother. "It was like being the sister of Moammar Gaddafi or Joseph Stalin." "The Mouth of Darkness," as Tash and Nomi call him, rules with an iron hand, excommunicating any who disagree with him. Excommunication is akin to living death in this community. Everyone, including members of his or her own immediate family, shuns the excommunicated. They are called ghosts. Ray, Nomi's father, is a quiet, devout man. He always wears a jacket and tie and sits outside in the evenings in a lawn chair watching the night sky. He writes reminders to himself of things to do the next day and leaves them on his shoes before he goes to bed. He's a man who likes his routine and, says Nomi, frequently, he and Trudie loved each other madly. So why did she leave? Tash and Trudie, though they didn't leave together or at the same time, have been gone three years when the novel opens. Nomi and Ray are still waiting for them to return. Before they left Nomi was a pious,

Life's hard questions

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

I found this book fascinating. On first reading, this book seemed to be one teenager's long downward spiral into depression, interspersed with a few beautiful or humorous moments. But a shadowy glimpse of a some more complex themes drew me back to it for a second reading, where I was delighted to find the writing tight and full of well-chosen imagery and recurring themes. The narrator, Nomi, writes near the beginning: "People here just can't wait to die, it seems. It's the main event. The only reason we're not all snuffed at birth is because that would reduce our suffering by a lifetime. My guidance counsellor has suggested to me that I change my attitude about this place and learn to love it. But I do, I told her. Oh, that's rich, she said. That's rich."Nomi chafes against the inflexibility and lack of forgiveness in many members of her religious community, but as she struggles to understand the undercurrents which have driven her mother and elder sister into the void beyond the town, she begins to be able to tap into the honesty of her family to imagine something bigger and better than the only place she knows. "I have a problem with endings," she writes, and she cannot satisfy her English teacher by drawing her essays to a neat close. In the same way, she can't seem to accept her pastor uncle's neat package of rigid definitions explaining her existence, with no mysteries or forgiveness for weakness. When a nurse at the hospital criticises her invalid friend Lydia for being so needy, Nomi objects 'But isn't that what a hosp...(ital is for?)" When the church throws out a man for being unable to overcome alcoholism, the reader wants to ask, "But isn't that what a church community is for?" Nomi has an innate sense that something is fundamentally wrong with her environment. But she recognises kindness, too, "in the eyes of people when they look at you and don't know what to say." Her uncle, "The Mouth", always knows what to say, and it never fails to be irrelevant and discouraging. But she values those whose love and concern go beyond the limitations of their prescribed answers, who can only love her and feel confused, without lashing out because they feel threatened by her ragged search to unite her family and find healing.Nomi's dad, Toews' best character, embodies this combination of deep love and confusion. He holds rigidly to the prescribed order of the community while gently falling apart with grief. Wonderfully complex, Ray wears a suit every day, even gardening, wins an award for perfect church attendance and listens to the radio hymn programme every night. But he spends nights secretly rearranging rubbish at the dump and slowly selling off the household furniture while letting his daughter see, with a sad and affectionate humour, that he doesn't know the answers. Toews addresses two different kinds of nostalgia: the oppressive desire of The Mouth to cling to concrete vestiges of a past lifestyle, such as the town's windmill, and Nomi's fon

Life's hard questions

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

I found this book fascinating. On first reading, this book seemed to be one teenager's long downward spiral into depression, interspersed with a few beautiful or humorous moments. But a shadowy glimpse of a some more complex themes drew me back to it for a second reading, where I was delighted to find the writing tight and full of well-chosen imagery and recurring themes. The narrator, Nomi, writes near the beginning: "People here just can't wait to die, it seems. It's the main event. The only reason we're not all snuffed at birth is because that would reduce our suffering by a lifetime. My guidance counsellor has suggested to me that I change my attitude about this place and learn to love it. But I do, I told her. Oh, that's rich, she said. That's rich." Nomi chafes against the inflexibility and lack of forgiveness in many members of her religious community, but as she struggles to understand the undercurrents which have driven her mother and elder sister into the void beyond the town, she begins to be able to tap into the honesty of her family to imagine something bigger and better than the only place she knows. "I have a problem with endings," she writes, and she cannot satisfy her English teacher by drawing her essays to a neat close. In the same way, she can't seem to accept her pastor uncle's neat package of rigid definitions explaining her existence, with no mysteries or forgiveness for weakness. When a nurse at the hospital criticises her invalid friend Lydia for being so needy, Nomi objects 'But isn't that what a hosp...(ital is for?)" When the church throws out a man for being unable to overcome alcoholism, the reader wants to ask, "But isn't that what a church community is for?" Nomi has an innate sense that something is fundamentally wrong with her environment. But she recognises kindness, too, "in the eyes of people when they look at you and don't know what to say." Her uncle, "The Mouth", always knows what to say, and it never fails to be irrelevant and discouraging. But she values those whose love and concern go beyond the limitations of their prescribed answers, who can only love her and feel confused, without lashing out because they feel threatened by her ragged search to unite her family and find healing. Nomi's dad, Toews' best character, embodies this combination of deep love and confusion. He holds rigidly to the prescribed order of the community while gently falling apart with grief. Wonderfully complex, Ray wears a suit every day, even gardening, wins an award for perfect church attendance and listens to the radio hymn programme every night. But he spends nights secretly rearranging rubbish at the dump and slowly selling off the household furniture while letting his daughter see, with a sad and affectionate humour, that he doesn't know the answers. Toews addresses two different kinds of nostalgia: the oppressive desire of The Mouth to cling to concrete vestiges of a past lifestyle, such as the town's windmill, and No